Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Before suspended Marion Superior Judge Kimberly Brown was facing possible removal from the bench for dozens of disciplinary counts, she had difficulties in her prior court, according to recent filings arguing for the ultimate sanction against a judge.

Before suspended Marion Superior Judge Kimberly Brown was facing possible removal from the bench for dozens of disciplinary counts, she had difficulties in her prior court, according to recent filings arguing for the ultimate sanction against a judge.

The Indiana Supreme Court suspended Brown with pay Jan. 9, citing Admission and Discipline Rule 25V(B). The rule says any judge whose removal from the bench has been recommended by the Judicial Qualifications Commission shall be suspended with pay pending the court’s disciplinary ruling.

Before she moved to Marion Superior Criminal Court 7 in January 2013, Brown had been in Criminal Court 16 since 2009. There, she scheduled jury trials one day each week. But she didn’t preside over a jury trial in that court until May 2012, more than three years later.

Brown

BrownBrown instead “assigned the responsibility of presiding over jury trials in Court 16 to commissioners, senior judges or judges pro tempore,” according to the special masters who last month recommended the Indiana Supreme Court remove her. The masters’ report also says that on multiple occasions in Court 7, Brown continued jury trials even when space and court officers were available to try them.

Those findings are among the filings asking justices to remove Brown from the bench. Her last-minute apology, submission to discipline and request for a 60-day suspension she sent to the Supreme Court – along with an affidavit in her support from former Justice Frank Sullivan – will not be considered, the special masters ruled Jan. 2.

Allegations against Brown include wrongful detention of at least nine criminal defendants, failing to properly oversee her court, improperly supervising trials, failing to act on Court of Appeals orders, showing hostility toward parties who came before her, and retaliating against court staff who complained to the commission.

On Jan. 8, Brown unsuccessfully appealed to the justices to spare her suspension.

Brown “understands that the rule appears to be mandatory that she be suspended from the office with pay pending final resolution of the issue of sanctions pending before the court,” the judge argued in the filing from her attorney, Bingham Greenebaum Doll LLP partner Karl Mulvaney.

“(I)t is her preference to continue to hear cases in Criminal Division 7 in order to keep the court properly functioning.”

The filing says Brown “does intend to file a petition for review directed at the recommended sanction” by a Jan. 16 deadline that would further bolster her argument for a 60-day suspension based on such a sanction in similar cases.

But justices wasted no time ordering Brown’s suspension pending final discipline, ruling a day after she appealed to remain on the bench. “Hon. Kimberly J. Brown, is suspended from office with pay effective at the close of business on the date of this order. This suspension will continue in effect until further order of this Court,” Chief Justice Brent Dickson wrote for the court.

Brown’s career as a judge will be finished if justices fully embrace the commission’s recommendations.

“If the Court adopts the Masters’ and the Commission’s recommendations and issues an order of removal, the Commission asks the Court, at that time, also to find (Brown) permanently ineligible for judicial office,” Adrienne Meiring, counsel for the Judicial Qualifications Commission, recommended in a Jan. 3 filing.

Brown’s request to stay her suspension included her affidavit of Dec. 11 which the masters previously struck. She apologizes and says changes have been made in her court to address concerns raised in her disciplinary case. The filing also is supplemented with documents detailing the remedial actions taken after the commission’s investigation began.

Retired Monroe Circuit Judge Viola Taliaferro presided over the panel of three special masters who heard Brown’s weeklong disciplinary case in November. She noted Brown hadn’t shown cause for failing to file findings of fact after the hearing.

Taliaferro

TaliaferroInstead, “Brown by-passed the Panel of Special Masters” with her Dec. 11 filing that advocated a 60-day suspension and included Sullivan’s affidavit. “The submission was later supplied to the Special Masters by the Supreme Court,” Taliaferro wrote.

The commission asked the masters to strike the filings as untimely and outside the record, and the panel agreed. “In that evidence has been heard, concluded and the cause submitted to the special masters for ruling, Brown’s chance to apologize, show mitigating circumstances, and recommend proposed discipline has passed,” Taliaferro wrote.

The commission would be unduly prejudiced if Brown’s filing or Sullivan’s affidavit were admitted without the opportunity to cross-examine the parties, she wrote. The panel stands on its recommendation that Brown be removed from the bench but clarified that the masters do not recommend suspending Brown’s law license.

The panel filed 107 pages of findings of fact, conclusions of law and recommended sanctions for Brown Dec. 27 in what is believed to be the most extensive case against a judge in the history of the Indiana Judicial Qualifications Commission.

The special masters – Taliaferro, Boone Superior Judge Rebecca S. McClure and Lake Superior Judge Sheila M. Moss – made 281 particular findings in Brown’s case, along with conclusions that she violated numerous rules of judicial conduct.

Among them, the masters noted that in several bench trials that took less than a couple of hours to try, Brown frequently took breaks and continued them, particularly if the trial might go past 4 p.m. Prosecutors had to dismiss some cases because witnesses became frustrated by the proceedings and stopped coming to multiple court dates, the report says.

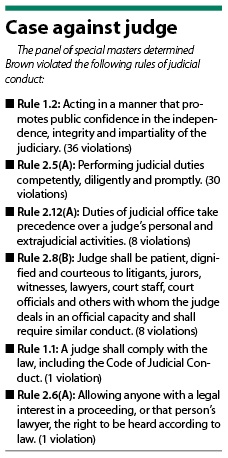

The commission proved more than 80 rule violations by clear and convincing evidence on 46 of 47 counts against Brown, the panel concluded. She was cleared on Count 22, in which she was accused of interrupting a public defender and treating him in an impatient and discourteous manner as he attempted to make a legal argument.

Brown also may have violated the law for terminating a former bailiff in her court who was among those who complained to the JQC, the panel concluded.

Along with the catalog of rule violations the panel found, it also noted in its general conclusions Brown’s refusal to be sworn during videotaped depositions before the commission. Refusing to be sworn “can only be viewed as signifying a lack of respect for the judicial process,” the masters concluded.

Brown also refused to turn over evidence the commission sought, the report states.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.