Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowPersistence, experience and a healthy dose of intuition — with those three attributes, two retired Indianapolis police officers have created a litigation support operation that local attorneys say provides invaluable investigative work and strengthens their cases.

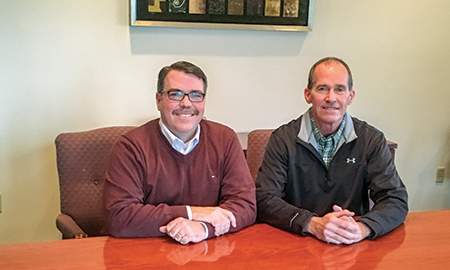

Since 2005, Omni Investigative Services has allowed Andy Starks and Tom Hildebrand to put their policing skills to work in the world of litigation. Drawing on their years of experience as Indianapolis Metropolitan Police Department detectives, Starks and Hildebrand now spend their days tracking down witnesses, uncovering hidden evidence and discovering information that most people wouldn’t know how to find.

“Omni has been vital in my practice in removing obstacles that often appear,” Chuck Roach of the Roach Law Office, LLC, wrote in an email to Indiana Lawyer. “It has become a valuable resource and allowed me to obtain results for my clients that would have otherwise been impossible.”

Transferable skills

Up until 2014, Starks and Hildebrand worked as partners for 12 years in IMPD’s Organized Crime Section Crime Action Team, performing undercover work such as robbery surveillance. Hildebrand retired from the force in 2014, followed by Starks in 2017, but their investigative work wasn’t over yet.

Instead, the duo turned their part-time work with Omni into a full-time endeavor, relying on word-of-mouth advertising to build a litigation support operation that requires them to combine their investigative know-how with the numerous connections they made through their police work. Transferring those skills to their work with attorneys was natural for the Omni partners, with Starks now spending about 90 percent of his time working on litigation support matters and Hildebrand focusing on financial fraud and pre-employment examinations.

From a litigation support perspective, Starks’ services encompass just about anything a private investigator would be hired to do: field surveillance, witness background checks, shooting photos and videos, assisting with accident reconstruction and more. A typical day might include observing the intersection where an auto accident occurred, looking into a party’s personal background or even performing business due diligence.

Starks then reports the information he gathers to his clients, who range from personal injury attorneys to family law practitioners and others in between. Personal injury firms often use Starks’ intel to support their version of the events leading up to an accident, while a family law practitioner might take his background research and use it to build a case against an opposing party in a child custody dispute.

Drawing on experience

Though they are retired police officers, Hildebrand noted that Omni’s work does not involve “standard” police work such as providing security services. Instead, he and Starks draw on their unique detective skills to uncover information their clients need to build a case, but that otherwise would be hidden.

The first key to discovering that information is to know where and how to look for it, Starks said. For example, if he’s investigating a personal injury case involving a crash at an intersection, he doesn’t just visit the intersection to check for skid marks or the timing of lights.

Instead, Starks observes the environment around the intersection, taking time to notice if any nearby businesses have security cameras that could have recorded the wreck. Attorneys might not think to look for cameras on their own, he said, but the footage could be invaluable in establishing exactly how an incident occurred.

Bill Winingham, partner at Wilson Kehoe Winingham LLC, has witnessed Starks’ natural investigative instincts firsthand when the private investigator has worked on his cases. Winingham recalled one case in which a witness remembered seeing a truck involved in a crash in a nearby neighborhood. Even though the truck was not involved in the collision, it had driven through the intersection just before the accident, so Winingham wanted to find the driver to ask if he could confirm which car had the green light.

Using the limited information the witness provided, Starks canvassed the surrounding neighborhood — similar to the work he did for IMPD — until he was able to track down the truck in question. Starks then located the driver, who indicated Winingham’s client had the right of way.

“I don’t think many people would take the time to drive around neighborhoods until they found the truck that met the description,” Winingham said. “He did a great job finding a critical witness.”

Required: people skills

But finding witnesses is only half the battle, Starks said. Knowing how to talk to them is just as important.

People often form their opinions of private investigators based on what they see on TV — tough men lurking in the shadows and tricking witnesses into divulging critical information. But the work he and Hildebrand do is much more human, Starks said, and involves talking to potential witnesses like they would speak to any other person.

Starks’ work often requires him to approach people unexpectedly, so his first step is never to demand information. Instead, he explains who he is, what he’s working on, and asks whether they’d be willing to share anything they know. His success in finding responsive witnesses is tied to the non-threatening way in which he approaches people, Roach said.

“Ninety percent of the time, those witnesses are more than willing to talk with me,” Starks said. “I just talk to them like a normal person would talk to somebody else, and usually that’s the best way to get info.”

Further, Omni’s services often bridge the gap between law enforcement and law firms, Winingham said. Sometimes police departments may be too busy to confer with attorneys on their cases, he said, but they are more willing to make time for retired officers such as Starks and Hildebrand. Through those connections, Starks can get a police perspective on how a crash occurred, which can work to Winingham’s benefit.

More than a feeling

The final skill the Omni partners said works to their clients’ benefit is one that can’t be taught: intuition. Years of police detective work has vested in Starks and Hildebrand a gut instinct that often leads them down a path that uncovers information critical to a client’s case.

Though he does not work in the litigation support realm, Hildebrand said his intuition helps him to know when a potential employee he is investigating for an employer might not be the right fit. Similarly, Winingham said Starks was once able to discern that information in a police accident report was inaccurate, and that discovery revealed Winingham’s client was not at fault. Starks was working on nothing bunch a hunch, Winingham said, but that hunch made the difference in the case.

Though their natural intuition might lead them down the right path, finding the end of that path is rarely easy, the former officers said. Sometimes their assignments require them to work quickly, but usually persistence uncovers the information they need.

That persistence, coupled with their law enforcement-honed expertise, is what sets Omni apart from other investigative companies, they said.

“It’s not like we’re reinventing anything,” Hildebrand said. “Most of it is persistence, patience and then a little bit of intuition.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.