Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowSix men from Indiana had their day in court. All proclaimed and maintained their innocence to the prosecutors and defense attorneys handling their cases and to the judges and juries presiding over the trials.

In the end, Hoosier courts handed down a combined sentence of more than 350 years, and those six men served an aggregate 83 years behind bars. Dozens of hands within the state’s criminal justice system police, prosecutors, defense attorneys, judges, court and law firm assistances at the trial and post-conviction levels have touched those cases at some point but didn’t stop what turned out to be eight decades of incarceration.

Defendants Richard Alexander, Harold Buntin, Larry Mayes, David L. Scott, Dwayne Scruggs, and Jerry Watkins have no connection because the facts of their cases, the charged offenses, criminal proceedings, and ultimate convictions were unrelated. But a common thread among those six is that each was wrongfully convicted and served time behind bars for crimes they didn’t commit before being exonerated.

It’s an ongoing saga unfolding nationwide, and the numbers continue to increase. Before 2008, Indiana had five exonerations. Now, six have been freed, and other defendants who’ve maintained their innocence from the start are attempting to obtain their own exonerations.

Those on the front lines say it’s part of a bigger puzzle that may have an undefined number of pieces and intricacies within a case, past and present. Variables can include underfunded police, a demanding public and political pressure, crime-tough prosecutors wanting to ease that pressure and ensure public safety, inadequate public defense, overwhelming court dockets, appellate judges bound by caselaw and precedent for deference to lower courts, and forensic crime labs that face backlogs in reexamining decades-old DNA, evidence, and criminal justice procedures.

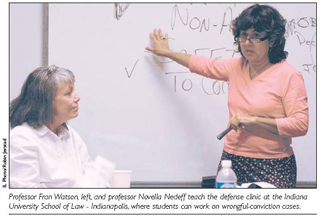

“It’s awful to have someone in prison you believe is innocent,” said Fran Watson, an attorney and Indiana University School of Law – Indianapolis professor who leads a criminal defense clinic that handles wrongful-conviction cases. “It’s not just enough to be innocent; you have to show the violation. As long as it takes, you’re particularly glad when justice gets done, finally.”

Hoosier exonerees

Five of the six Hoosier exonerees have been freed in the past decade; the most recent exoneration was in January and the earliest of these cases dates to 1993. The Innocence Project has taken on four more cases in recent years, according to staff attorney Jason Kreag, and so far, Watson said that Mayes’ release is the clinic’s only exoneration.

In January, Scott was freed from prison after 23 years and four months behind bars, which was part of the 50-year-sentence he received for the murder of an 89-year-old woman in Terre Haute during a home burglary. DNA tests last year implicated another man and a suspect in Kentucky has since been arrested.

Another man, Buntin, was released last year after serving 13 years from a conviction in a 1984 rape case. His case took a twist, though, in that DNA proved his innocence in 2005 but the Indianapolis man stayed incarcerated for almost two additional years because of misfiled paperwork at the court. That has led to disciplinary proceedings against Marion Superior Judge Grant Hawkins and Commissioner Nancy Broyles. Buntin has filed lawsuits against the jurists and county.

Indianapolis attorney Michael Sutherlin, who represents Buntin and is also working on a possible civil suit in Scott’s wrongful conviction, said the trends are becoming more apparent. He sees innocence initiatives exposing the fallibility of the criminal justice system overall, but he acknowledges there sometimes can be “a perfect storm of events” – brutal crimes, judges who want to be hard on criminals in an election year, communities up in arms, pressure on police to find the person who committed the crime, and pressured public defenders with overwhelming caseloads.

It can be tough to find the problems, particularly in older cases where evidence has been lost or damaged and witness accounts may no longer be available, Sutherlin and other attorneys say.

“These things can happen so easily, and these cases can open people up to the dangers of the system,” said New York attorney Nick Brustin, who has handled at least 20 wrongful-conviction cases nationally, including Mayes’ federal civil rights lawsuit stemming from a wrongful conviction and 21 years of incarceration. “Our hope is that these will lead to change.”

The Indiana connection

A part of a national network of law and journalism schools working on wrongful-conviction cases, the IU School of Law – Indianapolis clinic is dedicated to raising awareness about the failings of the criminal justice system and the thousands of innocent people in jail and on death row. The clinic has worked for the past decade with the New York-based non-profit Innocence Project, the nation’s most prominent organization devoted to proving wrongful convictions.

They often work with a wrongful-conviction clinic through Northwestern University and others throughout the country and cooperate with the Indiana State Public Defender’s Office, Watson said.

The Indianapolis clinic is currently the only one in the state affiliated with the network, Watson said. She and her students have filed appearances in about a dozen cases through the years, but they’ve put in hundreds of hours of work investigating and researching other cases that ultimately couldn’t be pursued.

While the wrongful-conviction clinic currently operates through the criminal-defense clinic at the law school, Watson said it will become independent in the future.

“This has the feeling of a movement and is all about what the system does wrong and what we can do better,” she said.

Studies of wrongful convictions suggest that thousands of innocent people are in jails and prisons across the country. The Innocence Project pursues 250 cases at any given time and reviews thousands of additional cases for legal action, according to Kreag, who handles all the wrongful-conviction cases from Indiana. Hundreds of letters are received each month, but only about 1 percent of those cases will be accepted, he said. A third of those accepted cases are ultimately closed because evidence has been lost or destroyed over time, Kreag said.

The most common legal issues in cases of wrongful convictions involve inaccurate witness identification, false testimony, government misconduct, and DNA-based evidence that later proves that person wasn’t the one responsible, according to Kreag. Indiana has adequate post-conviction laws that allow the DNA testing, but it doesn’t have any DNA storage laws or recorded interrogation statutes to improve the process.

Three-quarters of the DNA-based cases involve original misidentification of the perpetrator, Kreag said.

The Innocence Project reports that more than 220 exonerations have occurred nationally based on DNA evidence, but Kreag said that doesn’t take into account the criminal cases it doesn’t get involved with those lacking any biological evidence, such as burglaries, thefts, or criminal mischief convictions.

“Mistakes can be made so easily, and they are made routinely and that’s why it’s essential that everyone be aware no matter what part of the system they’re at,” Kreag said. “There’s no reason to think these mistakes can’t and aren’t happening in other cases we can’t get to, where there is not any biological evidence to review. We’re only seeing a small portion of what’s happening out there.”

To read more about Larry Mayes, read "After Exoneration," which appears in the Sept. 17-30, 2008, issue of Indiana Lawyer

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.