Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the Pike County courthouse, the staff commonly refers to the basement as the dungeon.

It is not a place many like to venture, with its stone walls, concrete floors and bare bulbs hanging from the ceiling, but the space has proven to be a handy repository for court filings and county records. Decade after decade, boxes of papers were carted down to the basement and left, rarely sorted through and cleaned out.

Not surprising, the basement became cramped with boxes, so county officials called the Division of State Court Administration to ask for help.

“We just wanted the public to be able to view and have access to records they didn’t know existed, and we also wanted to clean out the courthouse because we didn’t have room,” said Amy Hook, Pike County deputy clerk.

Tucked away in boxes and cabinets in county courthouses across the state is Indiana’s history. These original records trace births, marriages and deaths, property ownership, military service, and disputes that landed in court.

Divisions within the Commission on Public Records, like the state archives and the county records division, along with the Indiana Supreme Court’s Division of State Court Administration work together

to identify and preserve the important records. These efforts can be as mundane as going through boxes in a courthouse basement or as painstaking as repairing a tear in a 100-year-old map with Japanese mending tissue and special glue.

Included in Indiana Court Administrative Rules is an entire section detailing the schedule for retaining judicial records. The questions of which documents are to be kept permanently, which documents are retained at the county and which get transferred to the state are addressed in the retention schedule.

However, county officials may hesitate at the thought of tossing an old document or record book into the trash. And the result of not knowing what to do with all those papers, Hook said, is a flood of documents and little knowledge of what’s there.

Saving it for the next 100 years

Tom Jones, records manager at the Division of State Court Administration, fields the calls from the county clerks and organizes the on-site visits to help local communities determine what to keep, how to keep it and what to send to the state archives or local historical society.

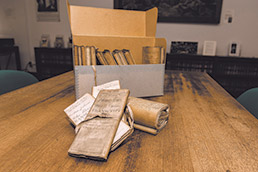

Court files, judgment books and dockets from state and county courts are among the holdings in the Indiana State Archives. Many of the books and documents are handwritten in cursive script (IL Photo/Eric Learned)

Court files, judgment books and dockets from state and county courts are among the holdings in the Indiana State Archives. Many of the books and documents are handwritten in cursive script (IL Photo/Eric Learned)During 2013, Jones made 67 visits to 31 Indiana counties. He has ventured down into basements, climbed up into attics and opened boxes and drawers to see what is inside.

Some requests for help come at a time of crisis when a county courthouse has caught fire or endured a flood. Jones and his colleagues will arrive soon after the disaster and help salvage what they can.

A fair amount of the materials Jones has reviewed has been generated by the local courts. Civil and criminal case files, Jones said, can tell the story of a specific period of time. He has seen early filings that were dominated by injuries from trains give way to auto accidents, underscoring the eclipse of the once mighty railroad by the horseless carriage.

“You definitely can see the legal history reflecting the general history of those times,” Jones said.

Recently, at the Indiana State Archives, Jim Corridan, state archivist, set an oblong box on the table and flipped the lid. Inside was a stack of Indiana Supreme Court case files from the 1800s. The grayish-brown papers had been tri-folded into tight bundles and the top edges were smeared with black dust, remnants from the former coal-heating system in the Statehouse.

Coupled with sorting and identifying historical documents, the state archives and state court administration preserve the records so they can be accessed not only today but also in the next century.

The project to preserve the Supreme Court’s case files was started under retired Chief Justice Randall Shepard and continued by Chief Justice Brent Dickson. An annual appropriation from the Supreme Court of $8,500 funds the preservation work.

To date, the state archives office has been able to refurbish and catalogue more than 30,000 filings from 1817 into the 1880s. A “few thousand” more Bankers boxes of case files, dating up to 1913, are on hand, and the archives is awaiting another 50 years worth of files to be transferred from the Supreme Court.

More than having a historical and research value, these files are caselaw, pointed out Corridan, who is also the director of the Indiana Commission on Public Records. They are precedent and still could be cited in opinions from the court in modern times.

The process to conserve the case files begins with a sponge to wipe off the dust and dirt. Then the papers are unfolded, often for the first time in more than a century, and placed under a brick to flatten them. In the conservation lab, experts will coax deteriorated pages apart and mend tears in the paper.

County books recording the local court judgments and orders as well as the docket are also housed at the state archives, kept on high shelves in the “stacks room” which has carefully controlled temperature and humidity. Some of those books can be as long as 2 feet and weigh as much as 30 pounds. Turning back the beautiful ornate cover will often reveal artfully flowing cursive handwriting.

Finding buried treasures

The Indiana Supreme Court case files from the 1800s were trifolded and bound with ribbon. (IL Photo/Eric Learned)

The Indiana Supreme Court case files from the 1800s were trifolded and bound with ribbon. (IL Photo/Eric Learned)The very paper used for the files, records and order books can slow the progress of Jones and his colleagues as they comb through documents in county courthouses. Especially with high quality and very expensive paper, like that from the mid-1800s, clerks were inspired to use every inch of available writing space, which means the state workers have to look beyond the cover and first pages when examining a government artifact. What may appear to contain just marriage licenses, for example, could also hold other records.

Going into the far reaches of the courthouses, Jones has discovered the remains of rodents and pigeons. But sometimes the hunts have yielded unexpected treasures.

In the Pike County courthouse’s basement, the staff found an enlistment book from the Civil War, a registry of widows and orphans, and the jail record from the 1800s which lists inmate crimes such as stealing a horse, pregnancy and tramp.

At the state archives, the Supreme Court files typically contain the transcript and briefs from the case as well as the order. However, some files have harbored a few cities’ original plat maps and one included the drawings from the 1870s of the courthouse in Marion County.

Perhaps most interesting has been the discovery of cases that, as Corridan described, have been lost to history. Among those forgotten court disputes are those dating into the 1820s and 1830s that concerned slaves and their Indiana owners.

“We’ll find some really intriguing things in the file that no one knows about,” the archivist said.

Shortly after he was elected clerk of the Owen Circuit Court three years ago, Jeff Brothers was shown the basement of the Owen County courthouse. There sat boxes and boxes of records and government papers likely dating from the inception of the county.

Upstairs the courthouse would soon begin making room for another Circuit judge who would produce more documents that would have to be stored somewhere.

Local officials already had been easing the overload by moving some of the documents to the local armory, and Brothers was devoting what time he could – even evenings and weekends – to sorting through the cardboard containers.

Ultimately, Brothers wants to retrieve some of what has been housed off-site back to the courthouse, but he does not want to do that by loading up the dumpster. Even when a plumbing repair flooded the basement, he did not throw things away but took batches of records to the armory and laid them out on the floor to dry.

In about a week, Brothers will get some help in his efforts to catalogue and preserve – Jones will be visiting.

“I believe in history,” Brothers said, explaining his drive to preserve the past. “History is an amazing thing to me. By doing away with something, you’re taking that (history) away from future generations.”•

—————————————-

Indiana Supreme Court case records online

The Indiana State Archives is creating a database of case files from the Indiana Supreme Court. Since the project started about 10 years ago, the archives office has entered more than 30,000 documents, dating from 1817 to 1882, into the database. Plans call for the work to continue until every case file has been catalogued.

The online database provides information on the county and court where the case originated, date of the Supreme Court hearing, parties involved and the disposition.

The database is available at http://incite.in.gov/dataentryapp/public.aspx

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.