Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe handful of Hoosier law firms that combined during the last two years highlight a pair of emerging trends of interest to those who watch law firm merger and acquisition activity — much of the combination activity nationally is being driven by small offices, and Indiana-based firms are largely absent from the marriage rolls.

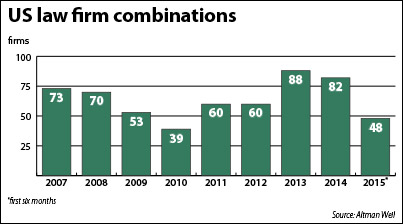

Legal consulting company Altman Weil has charted an increase in mergers and acquisitions among law firms since 2013. From January 2013 through June of this year, 218 firms have joined together, compared to the 159 mergers that occurred from 2010 through 2012.

Improved optimism about the legal industry’s future and firms returning to strategic growth plans are fueling the combination activity, said Eric Seeger, principal at Altman Weil. Law firms are not as fearful to merge as they were six or eight years ago when the economy was stalling. They are willing to consider opportunities that were deemed too risky during the recession, he said.

Ryan

RyanIn Indiana, Hall Render Killian Heath & Lyman PC has been courted by national firms wanting to add the practice’s health care expertise to their benches. However, according to managing partner John Ryan, the Indianapolis-based group is not interested in being acquired and is, instead, focusing on acquiring.

The firm is “progressively pursuing a growth strategy” by acquiring small firms in geographically attractive areas, Ryan said. In the recent past, Hall Render has secured footholds in Philadelphia, Denver and Washington, D.C.

The strategy of joining with a small firm is one many managing partners across the country are pursuing.

The strategy of joining with a small firm is one many managing partners across the country are pursuing.

Of the 48 law firm mergers and acquisitions that happened in the first six months of 2015, a total of 28, or just over 58 percent, involved a firm with five or fewer attorneys. The proliferation of small firm acquisitions began in 2014 when 59 percent of the combinations involved offices with two to five lawyers.

Firms are waiting for suitors to call, Ryan said. Hall Render rarely gets a cold shoulder when it reaches out and, in fact, is getting courtship offers from some attorneys and small firms that want to align with the Indiana firm.

Bigger firms

But mergers between large firms are still happening. Most notably in January of this year, the global law firm Dentons announced its intention to merge with the Dacheng Law Offices of China. This will make Dentons the world’s largest law firm with more than 6,000 attorneys.

The Indianapolis market saw significant mergers during the recession and the early part of the recovery. Ice Miller, Faegre Baker Daniels and Taft Stettinius & Hollister were part of that, but the activity has quieted down since the end of 2012.

Declining to speak specifically about Indiana law firms, Seeger said he expects the merger activity to continue at a high level, and he would not be surprised to see a deal announced by the end of the year that included a large firm in the middle of the country.

Ryan agreed. He noted that the Indiana market had a rush of mergers that came before the rest of the legal industry, but he does not anticipate Hoosier firms will become wallflowers.

“I think we’re going to see merger activity continue at a fevered pitch for at least the next couple of years,” Ryan said, “and I do anticipate it will involve an Indiana law firm.”

Shifting attitude

Farmer

FarmerIn the late 1990s, Bamberger Foreman Oswald & Hahn LLP in Evansville grew by acquiring small and solo practices in neighboring rural counties. That was a good growth strategy at the time, said the firm’s managing partner Terry Farmer, but it has since been curtailed as the market has changed.

The attorneys running those county offices eventually retired and Bamberger Foreman found young lawyers were not interested in establishing their practices away from urban settings. At present, the Evansville firm is growing by picking up lateral hires. It is not actively looking for an acquisition, Farmer said, although it is not rebuffing small firms that make inquiries and, occasionally, it has initiated some conversations.

Bamberger Foreman’s switch in strategy reflects a shift in attitude among law firms nationally. Prior to the recession, firms believed they had to grow or they would die, Seeger said. Today, in the post-recession economy, only half of the firms in business still hold that view. The other half is looking to maintain a footing in the market by trying to find ways to make their attorneys more productive.

A key to making the merger work is ensuring the cultures of the two firms are similar.

Jonas

JonasThe South Bend firm of Hammerschmidt Amaral & Jonas has had some suitors, but the courtship has never got beyond talking, said partner R. William “Bill” Jonas. Primarily, the major hurdle is compatibility of the cultures.

Jonas explained he is active in the St. Joseph County Bar Association; he does pro bono work and helps with the We the People program at one of the local schools. He worries if his firm was acquired by a bigger office outside the northern Indiana community, he would be required to increase his billable hours, which would force him to drop some of these other pursuits.

Culture can differ widely from firm to firm, Farmer said. Some offices may make decisions based on lifestyle concerns, while others want to maximize the dollar and tend to be more cold-blooded about their choices.

Also, there is the personality aspect. If the attorneys in one firm do not like their counterparts in the other firm, it will be difficult to merge, Farmer said.

Independent and entrepreneurial

Independent and entrepreneurial

At the three-attorney firm of Mattox & Wilson LLP in New Albany, managing partner Derrick Wilson said talking to another firm about merging might make sense, but the new firm would have to bring something that his office does not already have.

Small-firm attorneys tend to be entrepreneurial and want to control their destiny, he said, noting that he, too, possesses that independent streak. While joining a bigger firm may allow him to turn some of the administrative work over to the staff, Wilson prefers the simple bureaucracy of a small firm where decisions can be made without going through a committee.

Aside from formal mergers, small firms are sometimes enlisted by out-of-town firms to serve as local counsel. Jonas, who has a reputation for handling complex and messy bankruptcy cases, has represented clients referred from other firms. And when the volume of work on a particular case is too much to handle, Hammerschmidt Amaral has sent clients to outside attorneys.

Yet, Jonas said, even when he creates a referral arrangement he still has control over which outside attorney he will tap.

“For me, I’ve always been very concerned about the idea of practicing law with people I don’t know,” Jonas said. “Under the ethical standards of our profession, you have to have an awful lot of trust in the people you’re working together with. It’s hard for me to place that kind of trust in a 1,000-person law firm with offices (scattered across the country).”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.