Subscriber Benefit

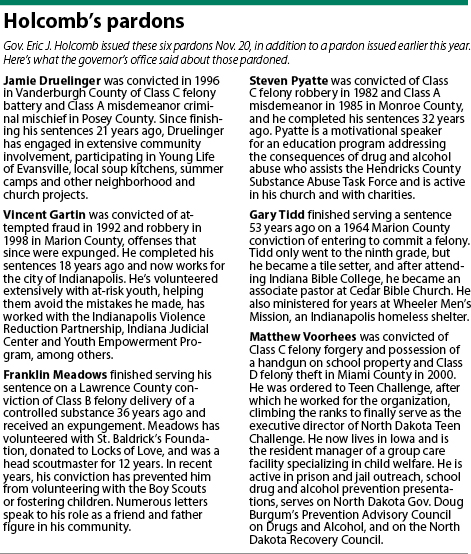

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowGov. Eric Holcomb issued six pardons on Nov. 20 — twice the absolutions granted by his predecessor, now-Vice President Mike Pence, during his four years as governor.

“While we cannot comment on the decisions made by previous governors … with seven pardons granted in his first year to date, Gov. Holcomb is not setting an unusual pace or precedent,” said Stephanie Wilson, Holcomb’s press secretary.

Records provided to Indiana Lawyer by the Indiana Register, Indiana Archives and Records Administration and Holcomb’s office demonstrate Pence’s three pardons in four years was an exceptionally low number compared to pardons issued by other governors in the past two decades.

“Gov. Holcomb’s decisions to grant pardons are based on 1. whether the individual in question has turned his or her life around and 2. whether the individual has made extensive and positive contributions that have benefitted his or her community,” Wilson said.

Pence did not reply to a message seeking comment sent to the White House Press Office.

Holcomb’s office detailed the stories of the six men he pardoned. But it was Holcomb’s first pardon as governor that highlights his differences with Pence on granting reprieves.

The Keith Cooper case

Keith Cooper was convicted of Class A felony robbery in 1997 and sentenced to 40 years in prison after he was accused of breaking into an Elkhart apartment in a robbery where Michael Kershner was shot and wounded. Kershner and other witnesses initially identified Cooper and Christopher Parish as the perpetrators, as did a jailhouse informant.

But over time the case fell apart. Witnesses recanted, and evidence pointed to another man. All witnesses — including Kershner — ultimately recanted their testimony against Cooper, and a deputy prosecutor testified for his exoneration. DNA evidence from the crime scene also vindicated Cooper, according to the Exoneration Project at the University of Chicago. A hat the shooter left behind contained DNA matching that of Johlanis Cortez Ervin, imprisoned for an unrelated murder conviction in Michigan.

Cooper was released after co-defendant Parish’s conviction was reversed by the Indiana Court of Appeals in 2005. Their wrongful convictions were based on false testimony by a jailhouse snitch and erroneous witness identifications that were manipulated by Elkhart Detective Steve Rezutko, who had previously been demoted for engaging in a pattern of similar misconduct, according to the Exoneration Project.

Parish sued the city of Elkhart and Rezutko over his false arrest and conviction and ultimately won a settlement of $5 million in 2014, according to the National Registry of Exonerations.

The robbery victim, Kershner, also testified to the Indiana Parole Board in favor of Cooper’s exoneration. The parole board unanimously recommended Cooper’s pardon in 2014. Pence declined to grant Cooper’s pardon request in September 2016, arguing Cooper first had to exhaust his remedies in court.

While Cooper in 2005 chose the certainty of his immediate release from prison over the prospect of a retrial, he continued to carry the stigma of a convicted felon. After his release from prison, he launched a mission to clear his name.

Feb. 9, Holcomb finally pardoned Cooper.

“Mr. Cooper’s pardon was never ‘rejected’ by then-Gov. Pence, Gov. Pence simply never made a decision on Mr. Cooper’s petition before leaving office,” said Charles F. Miller, a member of the Indiana Parole Board. “When he left office, Gov. Holcomb made the decision to grant. It is often the case for governors to leave some pardons undecided to be considered by their successors.”

Elliot Slosar served as Cooper’s attorney at The Exoneration Project. He said the difference between how the two governors handled Cooper’s case came down to a matter of character.

“In our experience, Gov. Holcomb seems to be a man of incredible courage and will do the right thing when presented with an opportunity to do so,” he said. “I think it just shows that one person, Gov. Holcomb, is there for the right reasons and is willing to use his executive power for the good of citizens in Indiana, and that Gov. Pence, in all of these moves that he made, (was) politically calculated for his next adventure.”

Slosar said he felt misled by the Pence administration and found it “shocking” that he failed to act.

Holcomb, Slosar said, “is looking at these pardon petitions as he should: With an open eye and an open heart, and is willing to make a courageous decision, and Gov. Pence was obviously not able to do that.”

Expungement’s role

Expungement’s role

Indiana enacted a sweeping expungement law in 2013 that allowed individuals to erase their criminal records. The goal of the statute was to give ex-offenders who had not committed another crime a second chance. The law was revised in 2014.

Miller said this change has opened another avenue for those who might have otherwise only considered asking for a pardon.

“Previously, only a pardon removed or hid the conviction from a criminal record so employers or the public could not see the petitioner was convicted of a crime. Now that petitions have the easier (and less discretionary) expungement route, parties will usually choose that route instead,” he said.

Slosar, though, said a gap in the expungement statute in Indiana meant that there was no requirement of the actual arrest being removed from Cooper’s record post-pardon.

“Even though Keith was granted an actual innocence pardon, we had to ask the court to not only expunge the conviction from his record, but the arrest from his record as well,” he said. “And, that has a lot of meaning for Keith and people like (him) because every time they are driving in a car, a police officer could do a search of the plate and look at arrests that somebody has on their background, regardless of whether those arrests resulted in a conviction. You could essentially become part of a criminal investigation based on an arrest which in our case the governor acknowledged resulted to a wrongful conviction. The arrest should have never happened in the first place. … I hope that it can be fixed at some point so that pardons not only result in the expungement of a criminal conviction, but in arrest as well.”

Reasons for hesitancy?

Frances Lee Watson is a clinical professor of law at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law and directs the Wrongful Conviction Clinic. Watson served as Slosar’s Indiana counsel in Cooper’s case.

Watson said worries over potential political blowback may be one reason governors are hesitant to issue pardons.

“Politics as it is, you don’t want the headline that says the person you gave the break to messed up again,” she said. “If you give a pardon, commute a sentence, give somebody a break, the last thing you want is for that person to make headlines doing more bad acts,” which could have negative political implications. “It’s the same thing with a judge letting somebody out on bond.”

Slosar said he agreed, but said such considerations shouldn’t have prevented Pence from granting Cooper’s actual innocence pardon.

“I think generally governors take those kinds of risks into account before they make a decision,” he said. “Around the country governors have issued actual innocence pardons. … And it happens because courts are known to fail people, especially those who are wrongfully convicted.

“In Keith’s case, it wasn’t really an issue because he had never been convicted before of a felony and he has never been convicted after his release of a felony. Gov. Pence had a decade’s worth of evidence to show that Keith Cooper wasn’t going to commit a crime or do anything that would embarrass him. … He was innocent before he went in and was just as innocent after he came out.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.