Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowYouth incarceration in Indiana has been on a steady decline for years, with experts in the legal field pointing to an emphasis on diversion and other patterns in youth behavior more generally as explanations for the downward trend. And recent legislative efforts may help sustain the momentum.

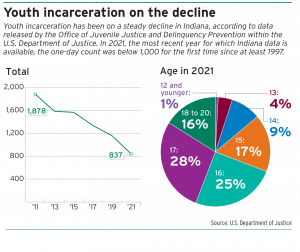

In 2021, the most recent year for which data is available, there were 837 youth in residential placement in Indiana, according to one-day data from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention within the U.S. Department of Justice. That was the first year with a count below 1,000 since at least 1997, although the DOJ data isn’t reported every year.

The count includes those who are younger than 21 and were in a facility at the end of the day on the census reference date, making it a snapshot look at youth incarceration.

The trend in Indiana matches what’s been happening throughout the rest of the country, which has seen a 60% decline in youth incarceration, according to The Sentencing Project.

Tracy Fitz, juvenile resource prosecutor with the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council, said one of the main reasons incarceration numbers have trended down is because overall crime rates have also dropped.

That was also one of the takeaways in a DOJ report from 2022, which reported that the number of juvenile arrests nationally decreased by 58% between 2010 and 2019, meaning fewer youth were processed through the juvenile justice system.

Fitz also pointed to adoption of the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, which began in Indiana in 2006 and focuses on reallocating public resources from mass incarceration to investments in youth, families and communities. The initiative is in 31 Indiana counties, according to the Division of Youth Services.

There are also efforts related to diversion that, even though they’re too new to make an impact on data that’s currently available, could play a role in future counts.

Formalized diversion efforts

Fitz was part of an oversight committee created by the Indiana Legislature in 2022 that was tasked with developing a plan for collecting juvenile justice data, establishing procedures for the use of screening tools and assessments, and creating a plan for diversion grant programs, among other things.

The committee’s final report, which it submitted to the Indiana General Assembly and Commission on Improving the Status of Children in June, said that while there are some “overarching” best practices for effective diversion programs, the grants should allow for flexibility because programs can vary widely by jurisdiction.

Even before this formalization of diversion efforts in state law, Fitz said about three-quarters of Indiana counties were implementing some type of diversion programs anyway.

Joel Wieneke, senior staff attorney with the Indiana Public Defender Council, said there are two especially good things about formalizing diversion efforts.

First, House Bill 1359, which established the oversight committee, requires the use of a risk-and-needs assessment tool, a risk screening tool and a diagnostic assessment when evaluating a child at various points in the juvenile justice system to identify their risk for reoffending.

Second is the data collection component, which Wieneke said will hopefully lead to a better understanding of what’s working and what isn’t.

The effects of that legislation are still to be seen, but Wieneke said he hopes the decrease in youth incarceration is because of more investments in schools and better community programs for youth — everything from Little League Baseball to the Boys & Girls Club.

“Hopefully the biggest reason why is kids are just doing less acts that would be crimes,” he said.

‘We are better serving our clients’

Diversion efforts in Marion County through the county’s Public Defender Agency are showing early signs of reducing detention in juvenile cases.

The agency’s Early Intervention Team, or EIT, funded by a grant through the Public Defender Commission, provides a team of an attorney, case manager and paralegal to clients in juvenile delinquency cases.

The agency’s Early Intervention Team, or EIT, funded by a grant through the Public Defender Commission, provides a team of an attorney, case manager and paralegal to clients in juvenile delinquency cases.

A report with preliminary data from the team says the effect on detention has been “large and statistically credible” at three points throughout the case: immediately after the initial hearing, 20 days after the initial hearing and at disposition.

For EIT clients, the rate of detention immediately following the initial hearing was 31% for the analyzed period, compared to 47% for non-EIT cases.

“It’s been very helpful,” said Jill Johnson, who works in the Marion County Public Defender Agency’s Juvenile Division. “… We are better serving our clients.”

Before implementing the program, Johnson said the agency wasn’t keeping its own data on things like detention rates and case length.

Now there’s a dedicated team to help figure out what youth and their families need, Johnson said, so they can put plans together and hopefully avoid detention.

“I think we’re doing a much better job of connecting with youth and their parents as soon as possible,” she said.

What role has COVID played?

Josh Rovner, director of youth justice at The Sentencing Project, said one important thing to keep in mind when looking at youth incarceration trends is that the COVID-19 pandemic likely played a factor.

Looking nationally, while there has been a steady downward trend for years, the numbers for 2020 and 2021 appear as outliers, dropping significantly more than any years before it.

In 2019, for example, the one-day data from the DOJ showed 1,155 youth in incarceration. In 2017, that number was 1,335. In 2021, it was 837.

“I think that reflects what a strange world we were living in in 2020,” Rovner said, noting that there were fewer occasions for kids to be arrested with so many schools and stores closed and people spending more time at home.

He compared it to being on a diet and then getting the flu, causing you to lose another 10 pounds. The weight loss was already there, but the additional 10 pounds represents an anomaly.

Rovner said he doesn’t want to make predictions about what will happen in the future but anticipates the counts for 2022 and 2023 to tick up, even if they’re still in line with the long-term trend.

Rovner said he also doesn’t like making predictions about how far down the incarceration numbers could go, partly because it’s dependent on local factors.

“I don’t know that there’s any natural floor or natural ceiling,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.