Subscriber Benefit

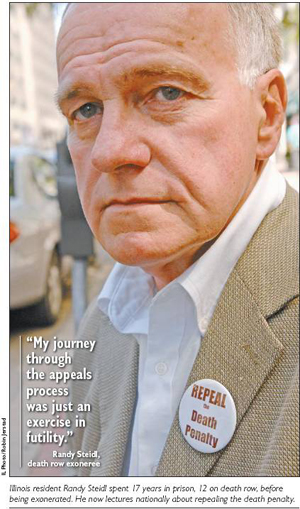

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn his years on death row, Gordon “Randy” Steidl watched a dozen men walk to their executions. The Illinois man said he would have made a similar final walk if it weren’t for a federal judge, who overturned his double murder conviction that had put him behind bars for a crime he didn’t commit.

For more than a decade, Steidl had unsuccessfully tried to prove his innocence from prison. But with that federal judge’s finding and a subsequent decision not to retry him, Steidl became the 18th person in Illinois and 123rd nationally to be released from death row.

Ultimately, he won his freedom after a life-changing 17 years of incarceration, 12 of which were spent on death row before he was moved after being granted a new sentencing hearing.

Steidl’s story is one that shares common elements with a growing trend of wrongful convictions being found as flaws in the criminal justice system are exposed.

“We have an adversarial system that isn’t always about justice, it’s about revenge,” Steidl said. “The death penalty is the ultimate hate crime, and it gives the public that pound of flesh they want because of what happened. But we shouldn’t always execute… we want an eye for an eye, and that isn’t what our courts should be about.”

Using his case as a way to send a message, the Indiana Coalition Acting to Suspend Executions thinks Steidl’s story can illustrate why this state should impose a moratorium on the death penalty. It’s a move recommended by an American Bar Association Panel in 2007 but one that hasn’t yet taken hold here even as national numbers reflect the criminal justice system is turning away from executions.

As part of a yearlong campaign statewide, the group referred to as InCASE is questioning the state’s current death-penalty system and educating people about its use.

“The stakes are very different with death penalty cases and exonerations,” said Will McAuliffe, the group’s executive director. “Being locked up for something you didn’t do is a nightmare, don’t get me wrong, but it’s even more horrific when there’s a ticking time clock on your life and the time you have to prove your innocence is fading away.”

Currently, a total of 135 people have been exonerated from death row nationally, including two on Indiana’s death row. Those figures are minimal compared to the larger number of wrongful non-capital convictions, which continues to grow as DNA evidence and other aspects of cold cases are explored.

The Indiana Public Defender Council reports that since 1977, out of the 93 death sentences that have been handed down in this state, only 19 of those individuals have been executed — eight since Gov. Mitch Daniels took office in 2005. The last Hoosier execution was in 2007 when Michael Lambert was lethally injected for fatally shooting a Muncie police officer 16 years earlier.

The two-year lapse in executions is evidence of what McAuliffe and others say is a national trend. States are moving away from the death penalty, both the carrying out of executions and the judges or juries ordering death sentences. Part of the trend involves the high costs presented to cash-strapped counties, and the legal system’s recognition that sometimes justice can go wrong, advocates say.

The two-year lapse in executions is evidence of what McAuliffe and others say is a national trend. States are moving away from the death penalty, both the carrying out of executions and the judges or juries ordering death sentences. Part of the trend involves the high costs presented to cash-strapped counties, and the legal system’s recognition that sometimes justice can go wrong, advocates say.

“It sounds like an impossible thing to those outside the legal world, but we get it wrong,” McAuliffe said. “That’s why we want a moratorium. Death is much more concrete than any prison sentence, and we want an honest exam of the system. It’s perfectly appropriate to approach capital punishment with a degree of humility without saying the sky is falling.”

An ABA panel report in February 2007 showed Indiana’s process isn’t fair or accurate, and is in need of reform on multiple fronts. The report described the system as being so random that it’s known in legal circles as the state’s second lottery, but that hasn’t resulted in any substantive changes so far. Legislation calling for a moratorium failed, and the Indiana Supreme Court has upheld these sentences.

McAuliffe admitted a moratorium is a long shot, but he said the primary goal of his group’s campaign is to put a human face to those being put on death row, and those who can speak best about the potential mistakes that happen in the criminal justice system.

That’s where Steidl comes in. Through a partnership, InCASE and the non-profit Witness to Innocence project seek to expand the dialogue about death-penalty use nationally. McAuliffe said Steidl’s story is important to share because it involves common wrongful-conviction issues such as inadequate representation, faulty eyewitness testimony, police and political pressure, and the eventual intervention of an outside group to assist with representation in exposing the flaws.

“People have to talk about these people and what’s happening in our legal system, but it has to be outside the legalese and court opinions,” McAuliffe said. “We need to hear these stories firsthand.”

Steidl recalled how he was tied to the July 1986 murders of a newlywed couple, who were stabbed about 54 times and then left in a burned home in Paris, Ill., before being found by firefighters. He didn’t know either victim and had an alibi, but police questioned the then-35-year-old in what he thought was just an attempt to get more information from locals; he was by definition “no choir boy” having had some misdemeanor run-ins with the law previously. Several months passed, and in February 1987 he was arrested for the murders.

Within 97 days, Steidl was arrested, tried, convicted following a nine-day jury trial, and sentenced to death in a case that didn’t have any DNA or forensic evidence and relied mostly on eyewitness testimony. He lost seven state appeals, with two evidentiary hearings failing to change anything and every state judge denying his requests for a new trial.

“My journey through the appeals process was just an exercise in futility,” Steidl said, noting that in late 1996 the Illinois Supreme Court did grant a new sentencing hearing on grounds of ineffective trial counsel assistance.

That resulted in a re-sentencing of life without parole, after prosecutors decided not to pursue the death penalty again, he said.

Because witnesses began recanting statements, the Illinois State Police began investigating the case again and uncovered mistakes in the process and how Steidl and his co-defendant had been wrongfully targeted and convicted, he said.

The Center on Wrongful Convictions at the Northwestern University School of Law took his case and helped persuade a federal judge to change course. In June 2003, U.S. District Judge Michael P. McCuskey in the Central District of Illinois ordered a new trial and the state’s attorney general later decided not to appeal that decision or pursue the case against Steidl. In his opinion, Judge McCuskey wrote that acquittal was reasonably probable if the jury had heard all the evidence.

The Center on Wrongful Convictions at the Northwestern University School of Law took his case and helped persuade a federal judge to change course. In June 2003, U.S. District Judge Michael P. McCuskey in the Central District of Illinois ordered a new trial and the state’s attorney general later decided not to appeal that decision or pursue the case against Steidl. In his opinion, Judge McCuskey wrote that acquittal was reasonably probable if the jury had heard all the evidence.

“They spent $3½ million to try and execute me, and I knew it was going to be tough to get another look after being affirmed so many times in state courts for 14 years,” Steidl said. “But finally, a real judge looked at the case and did what was right by the law. If we didn’t have the federal judiciary, I’d either be dead or still on death row.”

Steidl was released from prison May 28, 2004.

Since then, he’s been working in the manufacturing business and has reconnected with his family, all while traveling throughout the country to tell his story about his wrongful capital conviction. He spoke at the Indiana University School of Law — Indianapolis in early September to discuss his ordeal, and he plans to travel with InCASE to other parts of the state in the next year. He advocates that life without parole is a more just sentence, given the examples of wrongful convictions being found nationally.

Without knowing a true number of convicts who may have been wrongfully convicted or executed for those crimes, Steidl and McAuliffe say it’s impossible to know the true nature of justice delivered in our nation’s courts.

They find hope in the reforms happening, but argue that more must be done.

“These incremental reforms are part of this bigger picture of acknowledging the system isn’t perfect and that we’re looking for ways to fix it,” McAuliffe said. “But maybe we can explore whether we should be executing people in the meantime while we are looking at these reforms.”

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.