Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

Chances are the two teenagers are strangers and haven’t met even though they share a common bond through Indiana’s

juvenile justice system.

Robert Neely, 16, and Trevor Bridger, 17, both live in Elkhart County and have their own tales of how it took incarceration

to teach them a lesson. Both have been locked up in juvenile detention centers and spent time at the same Department of Correction

facility in South Bend, ordered by the same juvenile Magistrate Deborah Domine. They’ve been out since January and are

now hoping to complete their probations this year so they can leave the juvenile justice system behind.

This is the story of two young men who’ve gone through a local system the same as thousands of juveniles; they are

just two of the 82 youth sent to state-run juvenile facilities from Elkhart County, last year’s figures show. Both say

detention taught them a lesson they might not have learned any other way. While both speak positively of the actions their

juvenile magistrate took in helping them reform their lives, their intersecting storyline splits when it comes to their experiences

with counsel as they maneuvered through the county’s court system.

Their stories come at a time when Indiana ranks fourth in the nation for the number of youth being locked up, the state’s

juvenile justice system is lagging in what many call meaningful statewide reforms, and children’s access to quality

representation varies significantly from county to county and sometimes within the same juvenile court system.

Starting over

Neely grew up on the east side of Chicago. His dad is deceased and his mom still lives in Chicago. But Neely

Neely grew up on the east side of Chicago. His dad is deceased and his mom still lives in Chicago. But Neely

came to northern Indiana about three years ago to start over and live with his older sister, who’s now 26 and has held

guardianship for him for about seven years. Aside from Robert, she also takes care of their younger 14-year-old sister, two

10-year-old siblings, and her son and baby.

Neely has a history in both Indiana and Illinois’ social services systems and first made court appearances in Chicago

when he was 9 or 10. But his first Indiana court appearance came a few years ago before Magistrate Domine on a stolen property

charge.

Neely has been locked up in county juvenile detention about 10 times, ranging from about two weeks to four months, for various

things including possession of stolen property and probation violations that came from drug use and running from foster homes.

He has also been placed in group and foster homes after his sister declared he wasn’t listening or following rules,

and that he was at times too defiant for her to handle.

“I’ve never been out for a whole five months since I’ve been here,” he said. “I’ve spent

half my life being locked up.”

Magistrate Domine gave him a few chances, but his defiant attitude combined with drinking and marijuana use put a damper

on his progress and led to a seven-month stint at the South Bend Juvenile Correctional Facility last year. Neely would have

been one of the 126 juveniles the state reported being in the facility at the end of December. He was there from June 2007

to January 2008.

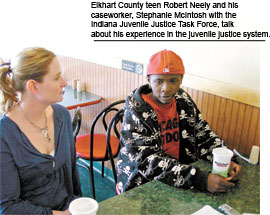

But since his release, Neely’s court-ordered family therapist Stephanie McIntosh with the Indiana Juvenile Justice

Task Force sees the teenager as a success story. She works with the Family Support Services that provides an intensive homebased

intervention designed as an alternative to out-of-home placement, offering treatment for youth and their families in the least

restrictive environment within the community. McIntosh met with him periodically when he was locked up last year and then

has been meeting weekly, sometimes going out to eat.

“Even thought it’s tough, rough, and it’s hard, there’s a lot of progress going on here,” she

said.

His last court appearance was in early February after his DOC release a couple weeks earlier. He’s looking forward

to his next hearing June 4 because he hopes to be released from probation; Neely hopes the court sees how he’s been

clean for a year, is doing well in school, and is working to change his ways.

Eventually, he’d like to enroll in a technical school to do some welding work or some skill such as advertising or

design, Neely said.

“I’ve been through it all, so now I’m trying not to go back to it because I’ve come from it,”

he said. “I came up here to start over, but didn’t. Now I’m starting from scratch and doing it myself. I’m

seeing where life takes me.”

Getting 'it'

A couple miles away from the pizzeria where Neely shares his story, Bridger sits at the kitchen table with his mom and court-ordered

family caseworker to talk about his experiences in the system.

The teenager first entered the system a couple years ago – a sex-related charge was dismissed and he was charged on

a residential entry offense. A February 2006 arrest for shoplifting led to a felony theft charge, and he was put on probation

for a year. But Bridger said he kept hanging out with the wrong crowd, smoking marijuana, and failing drug tests last year.

His first probation violation was a result of school tardiness, Bridger said. Part of his probation also involved not regularly

attending school and being late; he’d have to spend a day in juvenile detention if he was late to class. He racked up

about eight tardy violations so he spent a cumulative five days in detention, he said.

After his release, he returned a month later for violation of house arrest. Two days after that release, Bridger said he

was arrested after failing a drug test and that put him back in detention for a month before being sent to the DOC. Diversion

program options didn’t work out, and he was sent to a South Bend juvenile facility from June 12, 2007, to Jan. 14, 2008.

“I just didn’t take it seriously. It was all a joke,” he said. “All my friends had been locked up,

and I said I’d never be locked up. Next thing you know, I’m sitting in JC three times and then to the DOC.”

Bridger was supposed to be released in September and was counting down the days. However 15 days before his expected release

he stole some food because he was hungry; that violated a DOC rule and cost him three additional months of detention.

“I stole a cookie. One cookie. A moment of sugary pleasure … cost me three more months,” he said.

His new December release date also was postponed a month, but Bridger said the additional time taught him the most.

“That helped me more understand the consequences and what can happen. It taught me patience and helped me become more

mature,” he said.

Bridger earned an honors GED in the state facility, and he’s now taking part-time college courses at Ivy Tech Community

College and plans to enroll full time in the fall. He hopes that he’ll be released from probation by the end of this

month.

“It happened for a reason and I finally got ‘it,’” he said, noting that DOC taught him a lesson.

“You have to really want it, and you have to get ‘it.’ People who don’t, they need to go (to DOC)

and experience it.”

Legal experiences

The pair’s experiences with legal counsel varied, though.

Neely said he sees his courtroom and legal experience as a positive one. He described his public defender as nice, fair,

and always willing to discuss what was happening with the teenager before they entered the courtroom.

“He was nice and tried his best to not just keep me out of jail but to do better,” Neely said about his public

defender.

The two would meet at the detention center before court to talk about the case and make sure Neely understood what would

be happening in court, the teenager said. It seemed the attorney had reviewed his case before meeting. The attorney always

seemed to be preparing him for the outcome, flat out telling him if there was no chance Neely would be able to go home or

avoid jail. Before leaving court, the public defender would always ask Neely if there was anything he wanted to ask or say

to the judge.

Magistrate Domine “was cool” because she gave Neely several chances before sending him to the DOC, he said. She

always emphasized that what was happening in the home was important and played into his case, he said.

“Everyone helped me understand, but I was at the point where I took everything for granted,” the teenager said.

“I was just focused on getting out and not what could happen in the future that might put me back in jail.”

McIntosh feels fortunate to have worked in the Elkhart County courts because they’re reasonable and fair, and different

from what she’s experienced in other jurisdictions where detention alternatives vary and similar options don’t

exist. That’s what helped Neely, she said.

He hasn’t thought about what he might change if he could altar the legal system, but the teenager said nothing stands

out because he feels he was treated fairly by everyone involved.

“I can’t say there’s things I wouldn’t do, but I don’t know what I would do,” he said.

“If I had a wand, I’d show you and I wouldn’t have been there in the first place.”

In contrast, Bridger and his mom, Sharon, said they’d have much to change with the system.

At first, Bridger stayed in juvenile detention about a month longer than expected because his court date kept getting pushed

back. It would be rescheduled for the following Thursday, but then he would learn just before then that it was again continued

for the next week.

Bridger’s original public defender would inform him of the change, but that’s about all, Bridger and his mom

said. The lawyer didn’t seem briefed on anything.

Sharon Bridger said her repeated phone calls to the public defender often went unreturned, and she wasn’t able to get

answers about her son’s case.

His mom was searching for a local residential drug rehab to use rather than having her son sent to the DOC or a 30-day commitment

program, but she said that wasn’t available and her insurance wouldn’t pay for that type of program.

“There needs to be more creative options available,” she said.

She turned to other parents of youth in the juvenile justice system, and she said at one point someone told her what to expect

from the legal system.

“I’ve talked to a lot of parents … many seemed to feel that it didn’t really matter if you had an attorney

or not,” Sharon Bridger said. “The judge operated a certain way and nothing would change that.”

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.