Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowYou know the investing climate is unusual when a stock’s dividend yields more than bonds issued by the same company.

Take Indianapolis-based oil refiner Calumet Specialty Products Partners LP, whose dividend-paying stock had an annualized yield in early December of 8.23 percent, while its bonds yielded 7.21 percent.

Many better-known, blue-chip stocks crossed the same threshold as bond prices continued to rise last year. An overheated fixed-income market would be yet another challenge for income-seeking investors, who’ve had few low-risk options in the era of rock-bottom interest rates.

“Without question, this is the hardest environment investors have seen, probably in our lifetime,” said Terry Weiss, president of Wallington Asset Management, an Indianapolis firm that handles more than $400 million for wealthy individuals. “And it’s coming at a difficult time because, what do you have? You’ve got a lot of people who are retiring.”

“Without question, this is the hardest environment investors have seen, probably in our lifetime,” said Terry Weiss, president of Wallington Asset Management, an Indianapolis firm that handles more than $400 million for wealthy individuals. “And it’s coming at a difficult time because, what do you have? You’ve got a lot of people who are retiring.”

Local investment pros have different strategies, but they offered a common thread of advice: Don’t assume fixed-income means no risk.

“The last place you want to experience a loss in your portfolio is in the portion you thought was the safe piece of it,” said Brad Cougill, a partner at Indianapolis-based Deerfield Financial Advisors, which oversees $476 million for clients.

Investors poured more than $456 billion into global bond funds through Dec. 5, and $72.4 billion of that went into high-yield funds, or junk bonds, according to Boston-based EPFR Global, which tracks fund flows.

Money gushed harder toward bonds than in 2009 and 2010, when the total inflow was $354 billion.

The risk for bond investors is that yields are so low, even a slight rise in interest rates could erase the return, and continually rising rates could erode principal.

Cougill thinks the bond market will see some volatility over the next year, and he dispensed the same advice about sticking to an asset-allocation strategy that one often hears in the context of stock-market swings.

“I think people need to be prepared for that and know what they’re going to do,” he said.

With top-rated bonds yielding less than 3 percent, high-yield, or junk bonds became more attractive in 2012. Many of those bonds were held in new mutual funds and exchange-traded funds (which trade like stocks).

Winthrop Capital Management in Indianapolis looked closely at funds yielding 6 percent and found that most of their holdings were rated B or BB and yielded less than 5.5 percent. The remainder, which drove the overall return, went to bonds with double-digit yields.

“That’s the toxic stuff, and it has a high probability of defaulting,” Winthrop President and Chief Investment Officer Greg Hahn said.

Hahn isn’t against high-yield investing, but he said, “The question to ask is whether you’re getting compensated adequately.”

From a historic perspective, the answer to that question is no, he said. The yield spread between 10-year Treasury bonds, the safest investment, and junk bonds was near its tightest level in a decade in early December, he noted.

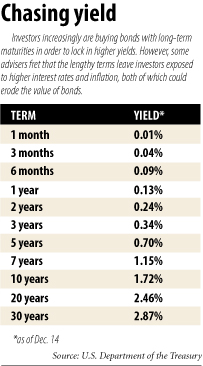

With interest rates near zero, the duration of a bond is as important to consider as credit quality, Weiss said. He doesn’t think interest rates will rise soon, but like other local wealth managers is careful not to invest in bonds going longer than five years.

Retail investors should look for bond mutual funds with durations no longer than five years, Weiss said. And given the low yields, he said, “I would be certain to be investing in mutual funds which have a very competitive fee structure.”

Fear of stocks justified?

The flight to fixed-income reflects a wariness of the stock market that’s persisted since the 2008 financial crisis.

“A lot of people are still running scared of the world, of the economy, of Washington,” said Don Woodley, principal at Woodley Farra Manion Portfolio Management in Indianapolis. “The safe industry is doing a bang-up business.”

Deerfield clients’ stock-market fears prompted the firm to adjust portfolios more toward high-quality bonds last year, Cougill said. As a result, total returns ranged from 5 percent to 8 percent.

“The stock market is up higher than that,” Cougill acknowledged. “But clients are saying, ‘Well that’s OK. We’d rather give up some of that upside.’”

Money flowed out of stock funds last year even as the Standard & Poor’s 500 posted double-digit returns. Investors pulled $67 billion out of equity funds through Dec. 5, according to EPFR Global, while the S&P 500 index returned 16 percent through Nov. 30.

Woodley, for one, thinks investors are missing an opportunity by sticking with what they see as safe havens. “Somehow people equate bonds with safety, and that’s not necessarily the case.”

Another option for investors looking for low-risk income is dividend stocks. Woodley, whose firm set up a dividend-stock mutual fund in 2011, looks for companies that not only pay dividends but increase them.

“It doesn’t have to be every year,” he said. “In a good year, they should be increasing their dividends and paying more and more to you.”

Utility stocks are an obvious source of dividends, and some yield 4.5 percent to 5 percent, Woodley said. (Dividend yield is the annual dividend per share divided by the share price.)

Utilities wouldn’t be attractive without the regular payments to investors. Earnings might grow 3 percent to 4 percent a year, Woodley said. “That’s good growth for a utility.”

Woodley also likes counter-cyclical companies like diaper and toilet-paper maker Kimberly-Clark, which has raised its dividend each of the last five years. The company’s earnings have also risen, an average 10 percent over five years, he noted.

“That growth is not spectacular. It allows an investor to rest comfortably,” he said.

Money managers like preferred stock because the dividends must be paid, even if earnings drop and the company cuts payments to common shareholders.

Preferred stock can seem as safe as a bond because it’s assigned a maturity date and par value, but there are risks, such as buying close to the call date, Woodley warned. “People can actually lose money if they buy the wrong preferred stock.”

Banking is another place to find rising dividends, though some money managers rule out the industry as too closely tied to potential economic shocks. For Hahn, who also likes preferred stock, banks are the only option to consider after utilities.

Each bank has a different risk profile, based on its particular niche and business strategy, Hahn said, so there’s no reason to rule them out.

“For decades, we just painted the brush over the whole industry,” he said.

When it comes to stocks in general, Hahn, who advises mostly institutional clients, is an uber-bear. At best, he thinks stocks will stay flat until global demand picks up, and he doesn’t think that will be in 2013.

“There really is no scenario we can come up with where stocks go on a roar,” he said.

Kip Wright, managing director at Kirr Marbach in Columbus, takes the opposite view.

“I think equities have the best potential going forward,” he said.

Finding sub-investment-grade bonds with upside potential became more difficult last year, he said. Yet investors still want returns of 5 percent to 7 percent, he said. “The only place you’re going to get those returns is by layering equities into your portfolio.”

Before the 2008 financial crisis, clients were willing to ride out events like the federal government’s fiscal cliff, Wright said. Lately, they can think only about locking in short-term returns.

“Looking for those guarantees are costing people a lot of money in this environment,” he said.•

This story originally appeared in the Indianapolis Business Journal.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.