Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIt all began in September 1962, when Atlanta insurance salesman George Burnett was accidentally connected to a phone call between University of Georgia athletic director James Wallace “Wally” Butts, Jr. and legendary University of Alabama coach Paul “Bear” Bryant. Burnett began taking detailed notes when he heard Butts, Georgia’s former football coach, seemingly divulge information about the Georgia team that would help Alabama later defeat the Bulldogs 35-0 in the 1962 season opener.

Burnett initially kept quiet about what he heard, but his eventual revelations gave way to a controversial expose and a United States Supreme Court case that reshaped American libel law. In a new book, “Fumbled Call: The Bear Bryant-Wally Butts Football Scandal That Split the Supreme Court and Changed American Libel Law,” a Hoosier author and journalism professor dives into the complicated case and examines its implications today — including the possibility that maybe justice wasn’t served.

“It was controversial, and I’m not the only one who has written about this case,” author and Ball State University professor emeritus David Sumner said. “There have been a lot of different authors and a lot of different views of this case, and I’ve seen some of that, but I try to get to the bottom of it.”

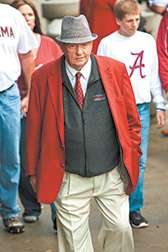

University of Alabama football coach Bear Bryant, above, settled with the Saturday Evening Post out of court, while Georgia coach Wally Butts proceeded to the Supreme Court. (Shutterstock.com photo)

University of Alabama football coach Bear Bryant, above, settled with the Saturday Evening Post out of court, while Georgia coach Wally Butts proceeded to the Supreme Court. (Shutterstock.com photo)Libel law revisited

Sumner first learned of the case of Curtis Publishing Company v. Butts, 388 U.S. 130 (1967), during a graduate school media law class. The case came on the heels of New York Times Co. v. Sullivan, 376 U.S. 254 (1964), which held that the First Amendment protects the publication of even false statements about public officials unless the statements are made with actual malice.

The New York Times case has become the standard of libel law, but the Curtis Publishing court expanded on the 1964 holding. The divided court ruled that public figures who are not public officials can recover libel damages if a false report is published that is based on “highly unreasonable conduct constituting an extreme departure from the standards of investigation and reporting ordinarily adhered to by responsible publishers.” In Butts’ case, the court determined Curtis Publishing, owner of the Saturday Evening Post, had acted highly unreasonably when it published a story stemming from Burnett’s allegations.

But something about the Supreme Court’s divided ruling didn’t add up for Sumner. Notably, there was evidence that Butts and Bryant — as well as three college football players — perjured themselves throughout the legal proceedings. Those inconsistencies intrigued the longtime journalism professor, so he decided to dig into the case records and draw his own conclusions from the facts.

“I’ve studied this case extensively, I’ve been going through all the court records, the transcript of the whole trial,” Sumner said. “I probably know more about this case than anyone else.”

Digging deep

Though Sumner’s opinion of the Bryant-Butts scandal leans toward a cover-up, “Fumbled Call” does not draw any conclusions for its readers, he said. Instead, Sumner strove to present the facts clearly and accurately to allow his readers to develop their own informed opinions.

Getting those facts meant frequent trips to Georgia, hours spent combing through trial records and newspaper articles, and in-person interviews with sources who either lived through the drama or knew a lot about it. A self-described archives nerd, Sumner took four trips to archive centers in Georgia to read court documents and depositions, then followed up case research with extensive media law studies.

Sumner was also asked to sit on a media law panel for a Georgia State Bar conference in February 2016, when he met Emmet Bondurant, an Atlanta attorney who worked on the Curtis Publishing case as an associate. The conference proved particularly fruitful for Sumner’s work on “Fumbled Call,” because he was able to connect with Georgia natives who could recall specific details from the game and its aftermath. One man at the conference, for example, said his father-in-law attended the game and came away thinking something was off.

“I was surprised the response was so positive in Georgia,” Sumner said. “It’s very well remembered there.”

General appeal

Sumner spent about five years researching, writing and editing “Fumbled Call” before North Carolina-based McFarland Publishing released the book in March. The book quickly became the top release in Amazon’s “Courts and Law” section, but readers say Sumner’s narrative appeals to both lawyers and laypeople.

Peter Canfield is a partner at Jones Day in Atlanta and is one of the organizers of the panel Sumner sat on at the Georgia Bar Media & Judiciary Conference in 2016. Like Sumner, Canfield said the conference benefitted “Fumbled Call” by introducing the author to primary sources who could revive the 55-year-old drama.

According to Canfield, those introductions paid off via a narrative that paints a picture of the importance of football in the south while also folding in the complex details of an important legal case. Though the key players changed their stories throughout the proceedings, Canfield said “Fumbled Call” walks readers through the twists and turns of the Curtis Publishing case without losing them along the way.

While many Georgia football fans still remember the ill-fated 1962 Alabama game, fewer recall the winding road the case took to get to the Supreme Court, Canfield said. But with “Fumbled Call,” the importance of the Curtis Publishing decision is once again a topic of discussion, he said.

Even from a non-legal perspective, Duke Haddad — a friend of Sumner’s who is also a prolific writer — said “Fumbled Call” makes the legal aspects of the narrative easy to digest and follow.

As a football official and Bear Bryant fan, Haddad read the book to learn more about the football side of the scandal but soon found himself contemplating the First Amendment issues the court would have to decide.

Though Haddad said nonlawyers could get bogged down in trying to figure out what libel is and how judges’ ideologies can affect court decisions, he said the book discusses those issues at a high enough level that readers only have to contemplate them if they choose. Otherwise, Haddad said from his experience, nonlawyers can take the legal aspects in stride and instead focus on the fate of the key players.

Legal takeaways

As a journalist, Sumner said the Curtis Publishing decision on libel law resonates with him professionally. The Saturday Evening Post made some mistakes in its reporting about the Bryant-Butts scandal, but Burnett’s notes are evidence that the conversation the two men had was not an innocent chat, Sumner said.

In light of those contradictions, Sumner said the court could have gone either way, a fact further evidenced by the 5-4 vote. Given that, Sumner said the decision underscores the fact that libel law is tricky to navigate and can often be fluid and subject to judicial perceptions.

That fluidity is what makes “Fumbled Call” interesting for all readers, Sumner said, whether they’re football fans, lawyers, both or neither.

“I feel like it shows all the complications and nuances of how a case proceeds to a trial, during a trial and after a trial,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.