Subscriber Benefit

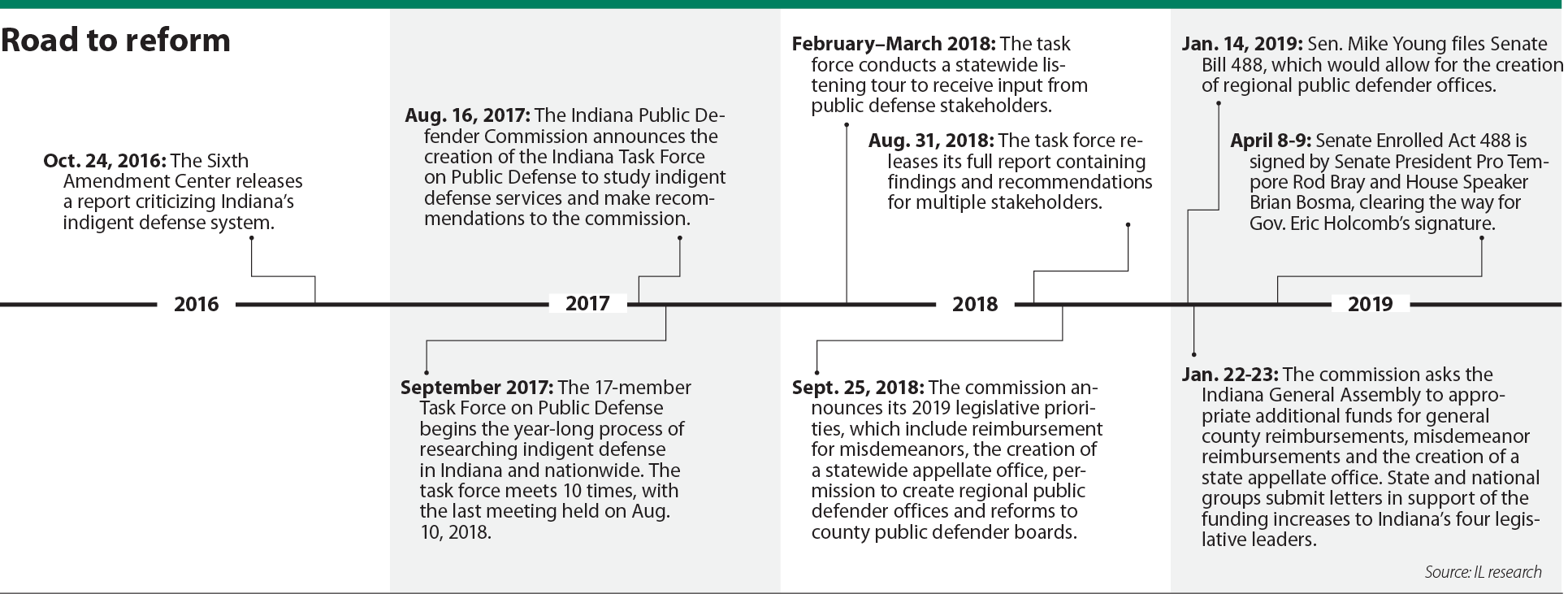

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the 2½ years since the Sixth Amendment Center released a report strongly condemning indigent criminal defense in Indiana, public defenders have pressed for reforms. Now, those efforts are beginning to bear fruit as the Indiana General Assembly takes action on reform legislation.

The process has been admittedly slow. The Indiana Public Defender Commission presented three key issues to the Legislature for consideration this year, but as the 2019 session nears its end, only one request seems to be a sure thing.

Even so, indigent defense reform advocates are optimistic. They saw the need to improve Indiana’s public defense even before the Sixth Amendment Center report, and they’re pleased other stakeholders are beginning to follow suit.

The key to maintaining that progress, defense advocates say, is for state leaders to realize that the responsibility to provide quality public defense falls to the state, even in a county-based public defense system such as Indiana’s.

Landis

Landis“There is a growing recognition at the state level that providing effective representation to those accused of crimes is a state responsibility,” said Larry Landis, vice chair of the Public Defender Commission and retired executive director of the Indiana Public Defender Council. “That’s what the Supreme Court says — the Sixth Amendment applies to the states, not counties, so it’s a state responsibility and a state constitutional right.”

Three asks

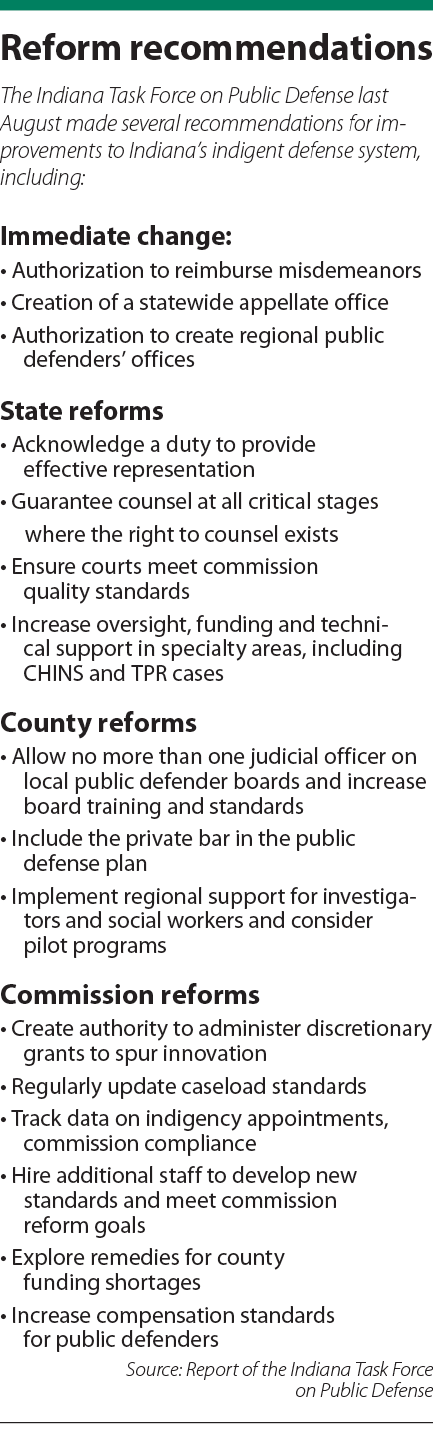

After the release of the Sixth Amendment Center report in October 2016, a Task Force on Public Defense was formed to study the provision of indigent defense services in Indiana and nationwide and to make recommendations on how to improve the Hoosier public defender system. The task force — led by retired 7th Circuit Court of Appeals Judge John Tinder — released its report in August 2018, and from that report came three key priorities for the 2019 legislative session.

Rutherford

RutherfordFirst, the Public Defender Commission wanted to authorize counties to form regional public defender offices. According to commission chair Mark Rutherford, smaller counties with limited resources often struggle to provide adequate indigent defense. But by forming a regional office, Rutherford said those counties can share resources to improve their work.

Second, the commission asked for additional funding to allow it to reimburse misdemeanor defense. Right now, the commission reimburses 50 percent of the cost of capital defense and 40 percent of the cost of other defense services. But misdemeanors are not currently part of that funding formula, a fact defense advocates say creates another hurdle on the journey toward constitutionally adequate defense.

Finally, the commission is pursuing the creation of a centralized appellate defense office. Like a regional public defender office, the appellate office would allow counties to share appellate defense resources and more easily locate qualified appellate attorneys.

Sharing resources

Young

YoungOf those requests, legislation that would allow for the creation of multicounty public defender offices has gained the most traction at the Statehouse. Indianapolis Republican Sen. Mike Young authored Senate Bill 488, which authorizes counties to pass ordinances allowing for regional public defender offices and lays out criteria for creating multicounty public defender boards.

Two key issues underscore SB 488. First, according to Rutherford, small counties often cannot incur the cost of providing full defense services, including hiring support staff, investigators, clerical workers, etc.

Second, according to Young, many counties — especially those that are strapped financially — have a system in which the judge contracts with a known pool of defenders. Even though the judges and defenders in those situations may act ethically, the optics of a defender arguing before a judge who appointed him aren’t great, Young said.

But under SB 488, counties that set up regional defenders’ offices can share funds, resources and even attorneys, which in theory would help lighten caseloads and offer more services for indigent clients. That could lead those counties to a point where they are able to comply with the commission’s caseload requirements, Landis said, thus allowing them to begin receiving state reimbursement. The bill requires just one of the counties’ auditors to handle reimbursement for all counties in the agreement.

But under SB 488, counties that set up regional defenders’ offices can share funds, resources and even attorneys, which in theory would help lighten caseloads and offer more services for indigent clients. That could lead those counties to a point where they are able to comply with the commission’s caseload requirements, Landis said, thus allowing them to begin receiving state reimbursement. The bill requires just one of the counties’ auditors to handle reimbursement for all counties in the agreement.

“What it does is it guarantees the perception that everyone has their day in court and in a fair and open hearing, and no allegiance other than to the client-attorney relationship,” Young said.

SB 488 passed out of both the Indiana House and Senate without a vote in opposition. At IL deadline, Gov. Eric Holcomb had not yet signed Senate Enrolled Act 488.

‘Misdemeanors matter’

The commission’s funding requests, however, aren’t progressing as well. Both the House and Senate versions of the state’s next biennial budget allocate $22.82 million to the commission, which does include additional funding for the existing county reimbursement scheme.

But what both budgets currently lack is the $5.7 million requested per fiscal year for misdemeanor reimbursement.

To both the commission and the Public Defender Council, gaining the ability to reimburse misdemeanors is key. Bernice Corley, Landis’ successor as head of the Public Defender Council, said that although misdemeanors may carry little to no jail time, their impact on a person’s life can be profound.

A family can be completely disrupted if a parent has to spend even one night in jail for a misdemeanor charge, Corley said. And if that person is convicted, it could negatively impact their ability to drive or get to work, among other possible implications.

“Misdemeanors matter,” Corley said.

The problem, Corley said, is that because many public defenders are overworked, they can develop a “processing mentality” when it comes to misdemeanors: negotiate a plea, then move on to the next case. Rutherford agreed, adding that the question shouldn’t be, “Will you take a plea?” Instead, he said, the question should, “Are you guilty, and what’s the appropriate sentence?”

Reimbursing misdemeanors can help eliminate the processing mentality by giving counties the opportunity to come into commission compliance, Corley said. Getting the reimbursement requires compliance with commission standards concerning caseloads and staffing.

s “They can give an actual defense,” she said, “not just be a processor.”

Crossroads

Legislators also have not included the commission’s request for an additional $4.9 million per fiscal year to create the statewide appellate office. That concept was also presented via House Bill 1453, but the bill never received a hearing in the Committee on Ways and Means.

The idea, Landis said, would be for the statewide office to be a counterpart to the attorney general’s appellate office. During its work, Landis said the task force frequently heard from judges who struggled to find qualified appellate defense lawyers, prompting the idea for an appellate office.

As the commission continues to work on public defense reform, Corley said the state is at a crossroads: it can either pay the cost of indigent defense now via funding requests and legislation, or it can pay the cost later via lawsuits that force reform. She and the other reform advocates are hoping the former comes true.

“We hope the state realizes it’s the right thing to do,” Corley said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.