Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAn ongoing assessment of the Monroe County Prosecutor’s Office is giving officials a look at how prosecutorial decisions have impacted racial and ethnic disparities.

Prosecutor Erika Oliphant worked with researchers from the Indiana University Public Policy Institute. The prosecutor’s office also partnered with the local branch of the NAACP.

Oliphant credited the NAACP and other groups in Monroe County for their work in studying disparities, which she said was mostly a volunteer effort.

There was some talk about adding a position in the prosecutor’s office to collect and distribute data, but Oliphant said she thought it would make more sense to go outside the office and rely on academic researchers.

Eric Grommon, who led the research team, said the research is split into two projects.

The first, which was funded by the county, centered around data, with a goal of figuring out the landscape of information available.

The Monroe County Prosecutor’s Office has a final report from the first project, which also includes recommendations.

Oliphant said she wants to release the report once she’s able to put together an accompanying response, which she hopes to have completed in the “next couple of months.”

What researchers found

Grommon, an associate professor at the IU O’Neill School of Public and Environmental Affairs at IUPUI, which houses the Public Policy Institute, described some of the research findings to Indiana Lawyer.

Researchers dug through the Indiana Prosecutor’s Case Management System, or INPCMS, along with the office’s informal worksheets to track case information.

Grommon said researchers were at the prosecutor’s office every Friday for about six months to go through physical case files.

The available data allowed researchers to get a good look at charging decisions and how cases were resolved — which Grommon called the “two anchors” of data at the beginning and end of a case.

There wasn’t much data, however, on how prosecutors worked through those cases from accessible INPCMS records.

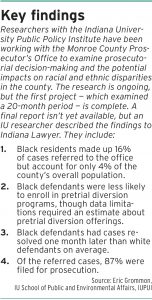

When looking at cases referred to the office in comparison to the overall population of Monroe County, Grommon said Black residents were overrepresented. Those residents made up 16% of referrals but only account for 4% of the county.

While Grommon said there was little evidence of disparities in charging decisions, case disposition and sentencing, that doesn’t mean there are “no disparities.” Instead, he said the overrepresentation that existed for Black residents on referral is being “reinforced” as the cases move forward.

Researchers also found that Black defendants were less likely to enroll in pretrial diversion programs, but there wasn’t data available on diversion program offerings. Grommon said researchers reached their conclusion by estimating that at least 70% of offers result in an enrollment.

Black defendants also had cases resolved one month later than white defendants on average — a disparity Grommon said is partly attributable to the prosecutor’s office, but also other parts of the justice system, such as defense counsel and judges.

The project also included surveying community stakeholders, with respondents pointing to the prosecutor’s office and, to a lesser extent, judges as having the power to address disparities.

Recommendations to come out of the research included revisiting how a person’s criminal history is accounted for, Grommon said. That includes putting more weight on convictions, as opposed to a person simply being arrested or having a case that was ultimately dismissed.

Another recommendation involves looking at how the prosecutor’s office screens referrals from law enforcement.

In the 20-month period researchers looked at, 87% of referred cases were filed for prosecution.

While Grommon said there isn’t a good source for national averages, he said one study of 15 prosecutor’s offices suggested the filing rate should be around 72%.

What’s next?

What’s next?

The second project, which started in 2022 and is scheduled to conclude by the beginning of 2025, builds off the first project, which included only criminal cases.

The second project also includes traffic cases and has a larger scope, going back through the last 10 years.

Also part of the second project is the creation of a public dashboard with INPCMS data so that people can see what the prosecutor’s office is doing. There are other offices across the country doing that already, Grommon said, but none in Indiana.

Additionally, the second project includes researchers working with officials in Lake County to explore the referral and processing of criminal and traffic infraction cases through the Lake County Prosecutor’s Office.

Though Oliphant is still drafting a response to specific recommendations, she said the prosecutor’s office has already started trying to track pretrial diversion program offers.

INPCMS is designed for case management, Oliphant said, not necessarily data collection.

But one nice thing about the system provider, she said, is that it can be customized for local needs, so the prosecutor’s office requested a simple toggle button in the system to mark if someone is eligible for a diversion program and if an offer is made.

‘Having that vision is unique’

Oliphant didn’t have to open her office to scrutiny from academic researchers who might go on to uncover some unflattering things, but she said she’s hopeful the work will help people understand that the office is trying to improve lives.

“I personally think it’s the right thing to do,” she said, “and this job isn’t really about me.”

Still, Oliphant said there will probably always be people who think she’s not doing enough or only paying lip service to problems.

“I can’t control how people feel and what they think about it,” she said.

Grommon credited Oliphant for “being vulnerable here.” He said Oliphant made it clear she wants to help initiate change.

“Having that vision is unique,” he said.

Oliphant recently received an award from the School of Public and Environmental Affairs for her work in promoting equitable justice: the John L. Krauss Award for Public Policy Innovation, named in honor of John Krauss, who founded the Public Policy Institute in 2008.

Being a prosecutor can feel like a thankless job, Oliphant said, so it was an honor to be recognized.

“I definitely felt like this was something where a large group of people should be recognized for this work,” she said, “… This was very much a group, a community project.”

Tom Guevara, director of the Public Policy Institute, said it’s important to recognize research that can inform public policy. Previous awards have gone to former Central Indiana Community Foundation President and CEO Brian Payne and the Indianapolis-Marion County City-County Council.

Oliphant emphasized that an award, although nice to receive, doesn’t mark the end of anything.

“I don’t think this work is done,” she said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.