Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowPublic water systems, manufacturers and farmers across Indiana and the nation are expected to face the most impact from new federal environmental standards that limit the presence of so-called “forever chemicals,” also known as per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances or PFAS.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took a historic step in April to protect communities from PFAS exposure, with the federal agency releasing a final rule that established legally enforceable limits on the level of PFAS found individually and as compounds in drinking water.

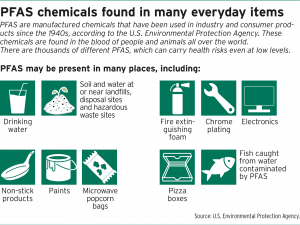

The chemicals can be found in a wide variety of everyday items, ranging from non-stick pans to microwave popcorn bags. But for all their beneficial uses, PFAS don’t break down easily and are also linked to various forms of cancer, heart and liver ailments and immune and developmental damage to children.

Michael Nelson, president of Indianapolis-based Nelson Law Group LLC and an environmental law attorney, said now that the rules have been established, businesses and public water systems will begin feeling the effects.

The EPA has estimated the annual cost to industry for compliance at $772 million.

The first to feel the pinch from the Biden administration’s PFAS road map will be the companies that use PFAS compounds in products they manufacture.

Nelson said that could include materials like fire extinguishing foam or non-stick cookware.

“I think those are going to be the biggest ones,” Nelson said.

In its announcement of the new drinking water standard, the EPA estimated that between 6% and 10% of the 66,000 public drinking water systems subject to this rule may have to take action to reduce PFAS to meet the new standards.

According to the agency, all public water systems have three years to complete their initial monitoring for these chemicals and must inform the public of the level of PFAS measured in their drinking water.

Where PFAS is found at levels that exceed these standards, systems must implement solutions to reduce PFAS in their drinking water within five years.

Nelson said it will be expensive for those water treatment systems that are forced to take action under the new standard.

He said those systems and the local municipalities they serve will likely try to identify where the PFAS contaminants came from.

Will Gardner, an Indianapolis partner in Taft Stettinius & Hollister LLP’s Environmental Practice Group, said the impact of any PFAS-related legislation or new federal rules varies, with some industries more affected than others.

One of those is farming, Gardner said, where PFAS chemicals sometimes show up in biosolids used as fertilizer by farmers all over the country.

“It’s kind of part of the life cycle now,” Gardner said of the chemicals.

Although environmental law attorneys and industries most likely to be impacted by the EPA’s new PFAS standard knew the new rules were coming, the recent announcement has sparked a lot of discussion with clients, Gardner said.

“We’ve been getting questions from clients from all over the place,” Gardner said.

In general, companies are taking a closer look at their manufacturing processes and how forever chemicals are used, he said.

How prevalent are PFAS chemicals?

The Indiana Department of Environmental Management defines PFAS as a class of synthetic organic chemicals that contain fluorine.

There are more than 3,000 PFAS, with some of them having been in use since the 1940s in products like textiles, paper, cookware, firefighting foams, and electronics.

Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) have been among the most used PFAS.

Those are two of the five “GenX Chemicals” cited by the EPA that will have limits under the drinking water standard.

In its announcement, the EPA stressed that the final rule would reduce PFAS exposure for about 100 million people.

The agency also announced there would be almost $1 billion in new funding available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to help states implement PFAS testing and treatment at public water systems and to help owners of private wells address contamination.

The agency also announced there would be almost $1 billion in new funding available through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law to help states implement PFAS testing and treatment at public water systems and to help owners of private wells address contamination.

The EPA rule has drawn strong opposition from many business and advocacy groups.

Tom Flanagin, the American Chemistry Council’s senior director of product communications, emailed a lengthy statement to Indiana Lawyer on behalf of the organization.

The ACC said that while it strongly supports the establishment of a science-based drinking water standard for PFOA and PFOS, the council feels the recent rule announced by EPA “takes an unscientific approach that is unacceptable when it comes to an issue as important as access to safe drinking water.”

It described PFAS as integral to thousands of products Americans use every day.

“PFAS chemistry is also critical to innovation. It’s not just about current uses, it’s also about enabling the safe use of PFAS in a manner that supports innovation and new product development. Some of the recent developments in battery technology, medicine, medical products, semiconductors and alternative energy rely on fluorochemistry,” the chemistry council’s statement read.

The council added that the Biden Administration’s Department of Defense has said that losing access to PFAS “would greatly impact national security.”

It also cited objections raised by the semiconductor industry, AdvaMed, a trade association representing advanced medical technology companies, and the U.S. Chamber of Commerce.

“Consumers should also know that PFAS chemistries in commerce today have been reviewed by regulators before introduction, are subject to ongoing review, and are supported by a robust body of health and safety data,” the chemistry council said in its statement. “PFAS chemistries are being regulated at the state and federal levels, including through the actions described in EPA’s PFAS Strategic Roadmap, and there has been significant work to address potential concerns with PFAS through Congressional action.”

State also taking aim

In Indiana, Attorney General Todd Rokita announced a lawsuit in April against 22 companies that, contrary to law, continued manufacturing substances known as “forever chemicals” despite these same companies possessing overwhelming evidence the substances posed serious health risks.

The lawsuit was filed in Shelby County, where a 2022 site investigation at the Shelbyville Army Aviation Support Facility found that PFAS contamination was likely caused by defendants’ aqueous film-forming foam — a product used for firefighting training and emergency response.

The companies have violated state and federal environmental regulations, according to the lawsuit, in addition to other laws such as the Indiana Deceptive Consumer Sales Act and the Indiana Product Liability Act.

“We’re taking action today to hold these companies accountable for their clear violation of laws designed to protect human health,” Rokita said in a news release. “For decades, they sought to hide research showing that their products were extremely dangerous to people everywhere, including Hoosiers. And they did it so they could make million-dollar profits at the cost of our health and well-being.”

According to Rokita, testimony from former employees and other evidence have shown that over several decades companies actively sought to hide internal research highlighting their products’ harm to consumers.

“Addressing the PFAS emergency that Defendants have caused requires substantial effort and expense to investigate, treat, and remediate the contamination,” Indiana’s lawsuit states. “The Defendants who created and profited from the creation of this problem must pay to address the PFAS contamination throughout the State.”

Rokita said that, elsewhere in the state, Grissom Air Reserve Base and Fort Benjamin Harrison are likewise contaminated as a result of AFFF, with elevated levels of PFAS detected in soil, sediment, surface water, and/or groundwater near fire training areas, fire stations and hangars.

The attorney general noted that IDEM sampling conducted between March 2021 and December 2023 revealed levels of PFAS above EPA Health Advisory Levels in public drinking water in the following counties: Bartholomew, Carroll, Cass, Clark, Crawford, Decatur, Elkhart, Floyd, Gibson, Harrison, Jackson, Jefferson, Johnson, Lake, Laporte, Madison, Marion, Perry, Posey, Scott, St. Joseph, Sullivan, Vigo and Warrick.

As the regulatory agencies catch up with the science, Gardner said he expects to see other PFAS chemicals come under closer scrutiny as well.

Gardner said that, for a long time, there had not been federal regulations for PFAS and states were operating in a vacuum in terms of how to regulate chemicals.

A lot of states have taken a more aggressive stance in terms of PFAS regulations.

Now, there is a definitive EPA standard for drinking water for specific PFAS chemicals, Gardner said, which takes some pressure off of states to develop their own rules.

He said the screening levels for PFAS, as noted in the EPA’s drinking water standard are extremely low, measuring in the parts per trillion.

Treating and mitigating groundwater can be very expensive, Gardner said.

PFAS chemicals are being found everywhere, Nelson noted, including places people wouldn’t think it would exist.

Some owners of commercial and industrial properties may have unknowingly purchased property with PFAS contamination and may have to test it before they can sell their sites.

Potential buyers may also ask themselves if they need to test a property before they buy it, Nelson said, especially if they plan on owning a site for an extended period.

“I think that’s going to slow down a lot of transactions,” Nelson said.

The science on PFAS is also still evolving.

In conversations with environmental consultants that he works with, Nelson said he’s learned there’s literally hundreds of PFAS compounds, but there aren’t tests for all of them.

“I’m not even convinced we know the best way to clean (some of) them up,” Nelson said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.