Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowPaul Henry Gingerich was 12 when Colt Lundy, 15, opened and closed the blinds inside his house in Cromwell, Ind., signaling the younger boy. Boosted by another 12-year-old, Gingerich climbed in through the window.

Lundy had a plan for the three boys to run away to Arizona, where his biological father lived. But first, he had to kill his stepfather, Phillip Danner. Gingerich later told authorities that he had hoped to persuade Lundy not to carry out his plan, according to court documents. But events quickly unfolded that April evening in 2010 that Gingerich later described as seeming “not real.”

Lundy slipped a 40-caliber Glock semiautomatic pistol into Gingerich’s hand. As Lundy trained his handgun on Danner as the man entered a doorway, Gingerich’s small hand rose likewise. Lundy fired. Gingerich says he closed his eyes and pulled the trigger. Danner was killed.

With Lundy behind the wheel of Danner’s car later that evening, he entered “Arizona” in a GPS and headed west. The boys were arrested after they stopped at a store in Peru, Ill., and a police officer grew suspicious about three children out in the middle of the night.

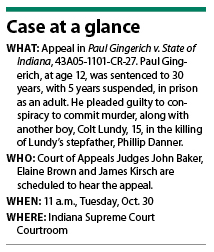

Gingerich, who had no juvenile criminal history, and Lundy were waived from juvenile court and sentenced by Kosciusko Circuit Judge Rex Reed to serve 25 years in prison as adults after they pleaded guilty to conspiracy to commit murder. Gingerich is believed to be the youngest person in Indiana sentenced as an adult. His appeal will be heard Oct. 30.

“I am very, very committed to this kid. He’s a good boy,” said appellate defense attorney Monica Foster, who argues that the trial court failed to determine Gingerich’s competency and denied him due process by rejecting his attorney’s pleas for a continuance after just four days to prepare for a hearing on whether Gingerich should be waived from juvenile to adult court. Foster argues that juvenile and trial court errors were so great that Gingerich’s plea agreement and conviction should be vacated.

Gingerich’s case has rallied those who question the merits of adult penalties for youthful offenders. Indiana Code 31-30-3-4, revised in 1997, allows that anyone over age 10 may be waived to adult court on a charge that would be murder if committed by an adult. That’s among the youngest in the nation, said Bill Glick, executive director of the Indiana Juvenile Justice Task Force Inc.

“It’s really completely inappropriate,” Glick said. “Especially given what we now know about adolescent brain development and youth brain development.”

“It’s really completely inappropriate,” Glick said. “Especially given what we now know about adolescent brain development and youth brain development.”

But prosecutors argue that Gingerich waived his right to appeal when his parents, Nicole and Paul Gingerich, consented to a plea agreement. “The waivers signed by the defendant and his parents were clear and unambiguous,” the state argues in court pleadings. “Enforcing the plea agreement entered into by a minor with the assistance of his parents and his lawyers is sound public policy. The defendant waived the right to challenge his conviction and to raise claims of legal and procedural error by pleading guilty.”

Gingerich’s parents signed a plea agreement after the state reduced the adult murder charge to conspiracy to commit murder, cutting the sentencing range by 20 years. “That he was looking down the barrel of a 45- to 65-year sentence must have weighed heavily on his and his parents’ thought processes,” the defense says on appeal. “A 12-year-old boy really has no meaningful ‘choice’ in this situation.”

Reed, the Kosciusko judge, said in court that the plea was sufficient to balance Gingerich’s age with the nature of the crime. “I have tried to explain that I believe the opportunity provided by the state of Indiana to go from a murder charge to a conspiracy to commit murder charge … offsets any aggravators or mitigators,” Reed said, according to court transcripts.

Before accepting the guilty plea, Reed rejected a defense request to put Gingerich’s case back in juvenile court. “I just don’t think I’ve got the discretion to say, ‘I don’t like this kind of a case, so I’m going to send it back,’” he said in court. Reed did not return telephone messages seeking comment.

Reed sentenced Gingerich to serve time at Wabash Valley Correctional Facility, which holds more than 2,000 adult felons in minimum and maximum security. Gingerich was 5-feet, 2-inches tall and weighed about 80 pounds at the time of his sentencing, and the Indiana Department of Correction instead placed Gingerich in the Pendleton Juvenile Correctional Facility.

Though Gingerich would have been sent to the youth incarcerated as adults unit at Wabash Valley, DOC spokesman Doug Garrison said there were a number of practical reasons not to place him there. “This kid would have been by far the youngest person over there, he’s very small in stature, and he’s better off for the time being with people closer to his own age,” Garrison said.

Garrison said there are 56 youths presently housed at the youth incarcerated as adults unit at Wabash Valley. According to DOC, 98 juveniles between age 15 and 17 have been sentenced as adults since 2010.

The case has generated several amicus briefs requesting Gingerich’s conviction be vacated. Michael Jenuwine of the Notre Dame Legal Aid Clinic filed a brief on behalf of Children’s Law Center, Inc., the National Juvenile Defender Center and Campaign for Youth Justice. He wrote that three U.S. Supreme Court decisions since 2005 “carved out separate jurisprudence with respect to children, differentiating them from adults based on their lessened culpability and greater amenability to rehabilitation.”

Another friend-of-the-court brief suggests that the process in Gingerich’s case moved far too fast, and that the defense attorney’s request for a continuance should have been granted. The Marion County Public Defender Agency said the four days Gingerich’s attorney had to prepare for his waiver hearing contrasted to the three months it is typically granted to investigate and prepare by gathering school and medical records and interviewing friends, family members and others.

The amount of time Gingerich’s attorney had to prepare for the waiver hearing interests Karen Grau, too. Grau is president and executive producer of Indianapolis-based documentary filmmakers Calamari Productions, which specializes in juvenile justice issues. She’s directed coverage of Gingerich’s and Lundy’s cases for about two years, including MSNBC’s “Young Kids, Hard Time.”

“The fact that Paul was so young when he was sentenced and the legal process was so fast,” Grau said, “that definitely warrants public exploration. How is that the case? Why is that the case?”

Grau and at least one other international documentary filmmaker have asked the COA for permission to record oral arguments in Gingerich’s appeal.

“The way Kosciusko County handled this from beginning to end was awful,” said Dan Dailey, who runs The Redemption Project. The nonprofit hosts a website – www.redemptionforkids.org – that raises money for Gingerich and other young offenders sentenced as adults.

“Paul is a Mr. Fix-It. He entered that house intending to de-escalate the situation and never really believed it was going to happen,” Dailey said. “His performance in prison reinforces that.” He said Gingerich is among the best students at Pendleton and is on the student council selected by facility staff.

Dailey said evidence about Gingerich’s character and more never got a day in court. He said Gingerich’s case remains rife with unanswered questions, particularly about motive. “The police never really figured out what happened,” he said. “The truth has never really come out.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.