Subscriber Benefit

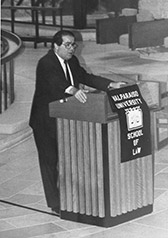

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia speaks at a function at Valparaiso University in 1996. (IL file photo)

Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia speaks at a function at Valparaiso University in 1996. (IL file photo)Supreme Court of the United States Justice Antonin Scalia was remembered as an intellectual judge who had a profound impact on the nation’s highest court, but also as friendly and personable in one-on-one conversations by Indiana judges and attorneys who had interactions with him.

Scalia died Feb. 13 at a Texas ranch at age 79, but his legacy will live on, according to many. Scalia is the first Supreme Court justice to die in office since then Chief Justice William Rehnquist in 2005. Before Rehnquist, the last justice to die in office was Robert Jackson in 1954.

Here’s what some Indiana judges and attorneys had to say about how they will remember Scalia:

Peter Rusthoven, partner, Barnes and Thornburg LLP

Rusthoven

RusthovenPeter Rusthoven’s first interaction with Scalia happened in the late 1980s, when the justices heard a case involving constitutionality of a control statute. Scalia wrote a concurrence, which Rusthoven said was right on.

“He cut to the point, what he found was absolutely controlling,” Rusthoven said.

His second was a decade ago when he met Scalia and his wife at a reception.

“He was gracious to a fault and very, very funny,” Rusthoven said. “It was fun watching his interactions with the other justices. Everyone just liked him and he treated everyone with the courtesy you would expect. He was very down to earth.”

Rusthoven said Scalia had the most impact of any Supreme Court justice in a generation.

“You had to take him on his terms, and he paid attention to what people who wrote the law actually said. Don’t use the law to say what you want it to say, that’s law.”

Loretta Rush, chief justice of the Indiana Supreme Court

Rush

RushChief Justice Loretta Rush admired Scalia and was effusive in her praise of him in an email to Indiana Lawyer.

“The originalist view Justice Scalia championed, and his rare gift for incisive prose and rigorous logic have been transformational across the ideological spectrum,” Rush said. “And it speaks volumes about his personal character that many of the most heartfelt tributes to him have come from the very people with whom he expressed the sharpest disagreement — ranging from his dear friend Justice Ginsburg to Professor Cass Sunstein, to name just two. The judiciary has lost a titan, but his legacy will be enduring.”

Gary Miller, Marion Superior judge

Miller

MillerMarion Superior Judge Gary Miller said he nearly dropped his phone when he got the alert that Scalia had died.

“I was definitely caught off guard,” Miller said.

Miller met Scalia two days before the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks at a professional responsibility conference on Long Island, he said, and he was very friendly.

“He was pretty charming, not like the stories of him with an attitude, not at all,” Miller said. “He enjoyed talking to people, talking to lawyers. It’s a different attitude with some people, and sometimes their impressions are not accurate.”

Miller said he knew Scalia could be sharp and pointed in an oral argument, so he understood how some people thought he could be a very gruff person, but that was not his experience.

He also said Scalia was very intellectual and it was always easy to follow his reasoning in a case.

“You may not agree, but you could always follow it,” he said.

Miller said the Supreme Court will miss Scalia’s constitutional interpretation.

Edward Gaffney, Valparaiso University Law School

Gaffney

GaffneyEd Gaffney had known Scalia for 40 years, beginning when they both worked at the Department of Justice together in the 1970s. Scalia then went to the University of Chicago Law School the same year Gaffney took a position at Notre Dame Law School.

“He had a focus on what was in the common good,” Gaffney said. “I think that’s overlooked, but it was especially so later in his career. He was so clearly a voice for limits on judicial power, very few Republicans see the advancement of that common good.”

Gaffney said Scalia was a proponent that justices shouldn’t do the heavy lifting on policy issues; that should be left to representatives to make that come to pass.

Gaffney also said Scalia had a great sense of humor, and that showed up in both his decisions and during oral arguments. He said his humor frequently interrupted people in their oral arguments, and it threw a lot of lawyers off their arguments.

Gaffney said Scalia was one of the fine writers in the history of the court.

“It’s not just wordsmithing, it’s a style of clarity that our progressive time would understand. He had a way of presenting what the premises of the argument were and could identify them and apply them as required to the facts of the case.”

He also said Scalia was rigorously consistent, not trying to decide too much.

“I remember a quote he had that I think sums him up. ‘If you’re going to be a good and faithful judge, you have to resign yourself you’re not always going to like the conclusion you’re going to reach. If you like them all the time, you’re probably doing something wrong.’”

Sarah Evans Barker, senior judge, U.S. District Court, Southern District of Indiana

Barker

BarkerJudge Sarah Evans Barker also had a couple of interactions with Scalia. She got to overhear a conversation between him and Justice Stephen Breyer over constitutional differences, which she said was quite a treat.

“It was fun and free-wheeling barbs,” Barker said. “He had a sharp wit, and he was as sharp as he was brilliant.”

Scalia was also a guest speaker at the 7th Circuit Judicial Conference when it was Indianapolis, and she sat at the head of the table next to him. The two had a pleasant conversation ranging on a number of topics.

“He was a wonderful guest,” Barker said.

Barker said Scalia talked about his clerks and why he has them, and he said it’s because he’s not good with computers and “needed them to format WordPerfect.”

Barker also discreetly handed Scalia Kleenex when he was low during the dinner. He at first bristled because he didn’t know what it was, but then thanked her.

Thomas M. Fisher, Indiana solicitor general

Fisher

FisherThomas Fisher argued in front of Scalia and the Supreme Court, and has a very vivid memory of his first time.

“During my first Supreme Court argument — which concerned the use of hearsay evidence at a criminal trial — Justice Scalia asked about supposed details of the case that he deemed particularly relevant, but that I did not recall. I had a panic-stricken moment where I thought, despite several weeks of exclusive focus on the case, ‘Oh my gosh, I forgot to read the case record!’” he wrote in an email to Indiana Lawyer.

“I felt the blood drain from my face in an instant, but just as quickly regained my composure and realized the justice was merely imagining details not in evidence. I did my best to correct the misapprehension (as gently as possible, mind you) and to use the discussion to my advantage, but Justice Scalia had a broader disagreement with my argument. He pressed me hard with many questions (as he is famous for doing); I had many answers, but none that satisfied him. Eventually Justice Ginsburg — a close friend of Justice Scalia outside the Court — came to my rescue, asking in effect, ‘Don’t you have another argument you would like to make?’ Boy, did I ever! The remainder of the argument went more smoothly, but alas we lost 8-1, without even getting Justice Ginsburg’s vote. The consolation was that the Court largely adopted the legal rule we proposed, though it did not apply to our case.”

Fisher had a more proud moment in August of 2015.

“I attended a Federalist Society conference in Colorado where Justice Scalia was one of the featured instructors. One day I was honored to be part of a small group lunch with the Justice, and was particularly proud when, having introduced myself as the Indiana Solicitor General, Justice Scalia responded that the development of the state solicitor role across the country was one of the most important advancements in Supreme Court practice during his time on the Court.”

Monica Foster, chief federal defender, Indiana Federal Community Defender

Foster

FosterMonica Foster argued a death penalty case in front of the Supreme Court and Scalia, and said she was terrified of him.

“I was arguing a death penalty case and I knew the chances of winning on the issue we had were not great, and that he would be the toughest to convince. He was not a great friend of people on death row attempting to vindicate their rights.”

Foster said she was so afraid of conceding something after Scalia asked her a question in oral arguments, she made a conscious decision.

“I decided I would repeat the question back to him, both to make sure I understood the question, and to buy myself time to come up with an answer.”

Although she did not win the case, but she was able to convince the Indiana Supreme Court to reduce the sentence to 60 years after a petition for post-conviction relief. Her client is still alive and well now.

“He was very, very bright man and it was one of the best professional experiences I’ve ever had,” Foster said. “I don’t get scared arguing too many cases, but there aren’t many who produce the kind of anxiety that he does.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.