Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen Allen Circuit Judge Thomas L. Ryan was beseeching the Legislature in the 1980s to create a senior judge program, he recalled that he and late Vanderburgh Circuit Judge William H. Miller gathered bipartisan statewide support for a vision: creating a pool of experienced jurists who could relieve congested courts and be tapped for their expertise.

“Senior judges are uniquely qualified to serve locally if the local judges recognize their aptitude to do so, but there are reasons why it doesn’t always happen that way,” Ryan said. He served 19 years as an elected judge, then another 14 as a senior judge in trial courts across the state, before he retired last year.

“The politics of supporting the viability of the service of a senior judge simply did not mature. It was unfortunate,” Ryan said of the program, now in its 25th year. “A lot of that was tied to compensation, and the unspoken controversy surrounding the presence of a stranger in my county when we’ve got an elected judge who should be there.”

Dickson

DicksonWhile Indiana’s senior judge program may not have flourished as Ryan envisioned, he’s hopeful and pleased it’s getting a fresh look from a committee announced last month, chaired by former Justice Brent Dickson, who is now a senior judge. The Supreme Court charged the seven-member committee with promoting the effective use of senior judges in trial and appellate courts, increasing participation of senior judges, and recommending expanded opportunities and uses for them.

Dickson said the group will have its first executive committee meeting Sept. 9. “We’re going to look and see if there are some ways we can improve senior judges’ compensation,” he said, calling that a first order of business. He said the group has received numerous ideas for expanding the use of senior judges, such as providing them e-filing training, using them to develop a best practices guide for courts, and assisting with judges who may be struggling with aging.

“Our plate is far from full and we’re hoping to develop ideas,” he said.

The senior judge program “does nothing better than to improve the trial courts and assist the trial courts that are already doing a good job,” said committee member and Senior Judge Cecile Blau of Clark County.

The senior judge program “does nothing better than to improve the trial courts and assist the trial courts that are already doing a good job,” said committee member and Senior Judge Cecile Blau of Clark County.

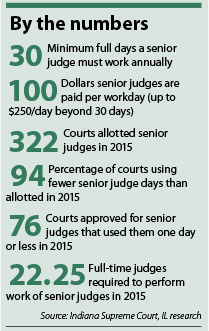

Senior judges work on average 40.75 full days a year, according to state court statistics. In addition to their state pensions of up to 60 percent of a comparable judge’s salary, they are entitled to pay of $100 per full day of service for the first 30 days worked, increasing afterward to as much as $250 per day, though that level of pay is seldom authorized. The most prolific senior judges topped out at about 88 workdays in 2015.

Advocates say senior judges are a bargain. The program cost the state a little more than $1.3 million in 2014, when senior judges did the work of 19.3 full-time judges — a comparative savings of almost $1.5 million.

This may be a good deal for taxpayers, but former Vanderburgh Superior judge, now retired former Senior Judge Scott R. Bowers, said it isn’t for the jurists. Low pay and the exploding cost of health care benefits are among factors causing jurists such as himself not to renew their senior judge status. Along with Ryan, Bowers is one of 14 senior judges who chose not to return in 2016, when five jurists — including Dickson and retired Court of Appeals Judge Ezra Friedlander — became senior judges for the first time.

This may be a good deal for taxpayers, but former Vanderburgh Superior judge, now retired former Senior Judge Scott R. Bowers, said it isn’t for the jurists. Low pay and the exploding cost of health care benefits are among factors causing jurists such as himself not to renew their senior judge status. Along with Ryan, Bowers is one of 14 senior judges who chose not to return in 2016, when five jurists — including Dickson and retired Court of Appeals Judge Ezra Friedlander — became senior judges for the first time.

“If they’re going to use senior judges, they ought to compensate them properly,” Bowers said. He said many judges in the past took senior status largely to retain health insurance for themselves and their families, but the state plan’s $8,000 deductible on family policies became too much sticker shock for some to continue just for that perk.

Senior Judge William E. Vance agreed he and his peers could be used more, and he acknowledged hearing complaints about low pay and rising benefit costs. However, “I don’t think you’re going to find too many senior judges who do that work for the compensation,” the former Jackson Circuit judge said. “I think most of us do it because we want to keep current, keep in touch, and develop relationships with other judges.”

Like many senior judges in more rural parts of the state, Vance travels to courthouses across several counties — in his case from Bedford to Greensburg. In such situations particularly, senior judges could be called upon more when judges have conflicts and need to remove themselves from cases. There are provisions for such appointments, but Vance said they’re seldom used. Using senior judges instead of special judges would be more cost-effective, he said, especially in smaller counties where a conflict for one judge is likelier to be a conflict for others.

Bowers said he took pride in the work he did as a senior judge — in one setting working three days a month to relieve a backlog of traffic cases. This helped move trial settings from about a year out to about six months. Bowers sees senior judges as a key to judicial efficiency. He reasons that a senior judge assigned a docket of non-violent criminal cases, for example, would help move cases faster, in turn relieving local jail crowding.

Senior judges also could be vital in handling politically charged cases such as annexations, Bowers said, because they don’t have to worry about the next election. “If you have something that’s especially the subject of political passion, it’s easier to focus on the law if you don’t have to have your livelihood on the line,” he said.

He said in recent years, he was assigned to work in courts whose allocation of senior judges was capped at 10 days per year. “So I was scrambling to get in 30 days by the end of the year. These were very busy courts, and they would have been glad to have me there a bit more.”

Courts are assigned maximum senior judge days based on weighted caseload statistics, with most allotted 10 to 30 days per year. A handful of courts with a caseload measure above 1.81 are permitted unlimited senior judge days. Most courts don’t use nearly all the senior judge days they could have, court stats show.

Ryan said he’s hopeful the committee will take a fresh look at a program he called practical and wise. “It’s a service that should be meticulously studied,” he said. “There could be a network of judges that are particularly capable of performing special services.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.