Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the weeks before the Indiana Bar Exam, Christopher Engel’s life fell into a predictable pattern – wake up, study, work out, study, dinner, study.

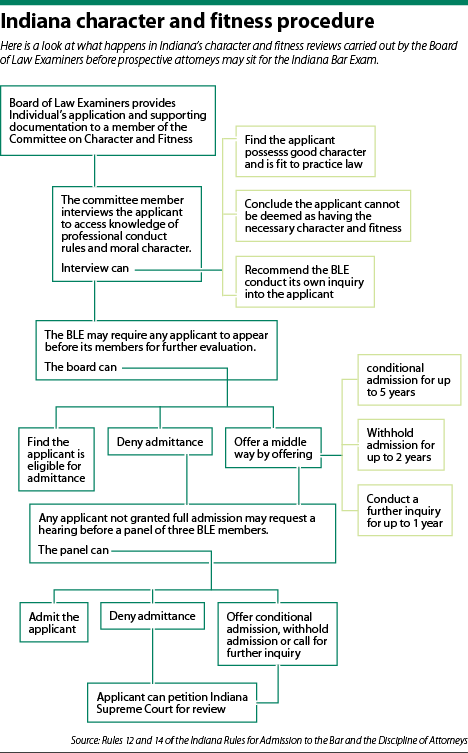

The two-day test was the focus for several weeks, but before he could sit for the bar, he had to complete a character and fitness interview. An attorney reviewed his record and asked him questions to judge his moral character and fitness to be a lawyer.

Engel acknowledged that in the worry of completing his final semester and preparing for the bar, he does not remember much about the interview.

He does not recall the evaluation being as stressful as the exam because, except for a speeding ticket in North Carolina he got at age 18, he had no serious transgressions to explain. His character and fitness interview was more of a discussion with the lawyer imparting advice of how to meet the demands of the legal profession.

“I found it to be a very positive experience,” said Engel, an associate at Krieg DeVault LLP.

Engel

EngelEvery jurisdiction evaluates applicants for character and fitness, according to the 2018 Comprehensive Guide to Bar Admission Requirements published by the National Conference of Bar Examiners in collaboration with the American Bar Association. But Bradley Skolnik, executive director of the Indiana Office of Admissions & Continuing Education, said Indiana is among a handful of states that mandates all applicants for the bar undergo a character and fitness review.

Likely, the newest pool of law school graduates preparing for admission are like Engle, focused on the actual test. Even so, Skolnik sees the evaluation as just as essential as the actual bar exam.

“It’s important that lawyers have not just the requisite knowledge of the law and a reasonable ability to represent a client but also demonstrate that they have the necessary character and integrity to be members of the bar,” Skolnik said. “While the bar exam probably is the most visible thing the Board of Law Examiners does, character the fitness is every bit as vital in protecting the consumer.”

Questioning past behavior

Applicants to the Indiana Bar can be denied admission if the BLE believes they do not have the integrity required for the profession. A parking ticket might not be a problem, but a slew of parking tickets can raise concerns. Likewise, criminal matters, civil lawsuits or academic issues that led to probation or questions about the person’s honesty can give the board pause.

In recent years, character and fitness interviewer Mary Nold Larimore has noticed more law school students getting involved with the criminal justice system for underage drinking while studying for their bachelor’s degrees. She attributes the increase to the stricter approach colleges are taking toward students consuming alcohol.

For the most part, Larimore said, applicants with an underage drinking citation are embarrassed and regret that it happened.

Larimore, partner at Ice Miller LLP, views such matters in context, looking at what the applicants did to address the situation and how have they behaved since. With all the individuals she interviews, she wants to see a seriousness and understanding of the obligations placed on lawyers.

“Everybody makes mistakes in life,” Larimore said, noting it is important to see “what has been their approach to that mistake, how have they handled it and how would they handle it in the future.”

Although the BLE does not track the number of applicants who are stopped because of character and fitness doubts, Skolnik said it’s a small percentage. The board does have the option of offering conditional admittance or delayed admission instead of a denial.

“I think we have one of the better processes in the country,” Skolnik said of Indiana’s character and fitness interview. He added he sees the evaluation as demonstrating to the applicants that lawyers are held to high standards of conduct.

Even though he was tripped up by the character and fitness evaluation, Jon Olinger agreed the process is necessary because it underscores the responsibility lawyers carry.

Olinger, 53, was a real estate agent for many years prior to going to law school. Helping people make what often was the most important transaction of their lives was demanding work but it did not have the level of stress he now feels as a lawyer. His clients today are facing the possibility of losing custody of their children or going to jail.

The potential consequences of the work attorneys do require the legal profession to uphold the qualities of fairness, trustworthiness and duty, Olinger said. “I want to be in a profession that polices itself and has standards,” he said.

Attorney discipline

Attorney discipline

Olinger, a 2016 graduate of now-defunct Indiana Tech Law School in Fort Wayne, was denied admission due to character and fitness concerns the first time he applied.

He believes the interviewer recommended him, but two weeks later, he was called to Indianapolis to appear before the full Board of Law Examiners. His application, he speculated, raised a lot of questions because he did not include details such as his multiple eviction lawsuits he initiated as a landlord.

Before the full BLE, Olinger sat at one end of a long table staring at the members seated all the way around. For 10 minutes, they peppered him with questions, an experience he compared to making an oral argument before an appellate court.

The process was the same the next year when he applied again. After the one-on-one interview, he had to meet with the BLE, but having provided in-depth explanations on his application, he said, the entire event had a friendlier feel.

Olinger was admitted in 2017 and is a solo practitioner.

“I can’t really blame anybody but me,” he said of initially being denied admission. “It would have been nice having more guidance in filling out the application, but I didn’t ask.”

Karol Krohn, one of the estimated 240 Indiana lawyers who volunteer to do the character and fitness interviews, points to the change in attorney discipline cases as putting more emphasis on the need for reviewing an applicant’s record and personal behavior. The discipline cases, she said, seem to have swung from acts that merit a slap on the wrist to egregious, even criminal, conduct.

New attorneys entering the post-recession market are more vulnerable to running afoul of the professional rules because with fewer law firm positions available, many are having to open their own practices. They lack mentors to guide them.

In this atmosphere, Krohn, deputy consumer counselor for the Office of the Utility Consumer Counselor, questions the applicant not only about any misdeeds but also tries to learn why they want to be a lawyer and what they did in law school. She then writes her evaluation and makes a recommendation to the BLE.

The board provides a second layer of review, either accepting the assessment of the interviewer or undertaking its own examination of the applicant’s character and fitness. Krohn appreciates the extra look given to every evaluation.

She recalled one young woman who had no red flags on her application. The woman did well in the interview and eventually was working in a J.D.-advantage job when she was killed while driving drunk.

“It was terrible,” Krohn said, noting the young woman was intelligent, enthusiastic and gave no indication of having bad judgment. Even today, Krohn wonders if she missed something and continues to ask herself, “What could I have done?”

Nothing better

Applicants prevented from joining the bar because of character and fitness issues can try to get the determination reversed. They can request a hearing where they can present evidence and examine witnesses before three members of the BLE. If that fails, they can file a petition with the Indiana Supreme Court.

Kansas attorney Bryan Brown turned to the courts when he was denied admission to the Indiana Bar. The BLE had concerns about his character and fitness but Brown claimed he was targeted because of his religious beliefs. He filed unsuccessful lawsuits in state and federal courts as well as three petitions for Writ of Certiorari with the U.S. Supreme in 2010, 2012 and 2016.

At present, the BLE is not considering any changes to the character and fitness evaluation, according to Skolnik. The last change came after a federal court found in 2011 that Indiana’s question about mental health was “overly broad” and violated the Americans with Disabilities Act. Since then the inquiry has been narrowed to asking if the applicant has been diagnosed or treated for a mental health condition within the last five years.

Larimore devotes part of her interviews to getting the applicants to think about their future reputations and the adjectives they would want used to describe themselves as attorneys. A lawyer, she explained, does not pedal widgets but instead sells trust, judgment, experience and wisdom. Once attorneys misstep, the damage to their reputations can be long-lasting.

The character and fitness evaluation is not perfect, but Engel said he cannot think of a better system. Determining whether someone will act morally when dealing with clients and opposing counsel is difficult to do in a comprehensive way during an hour interview.

“I think the profession itself is one long character and fitness interview,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.