Subscriber Benefit

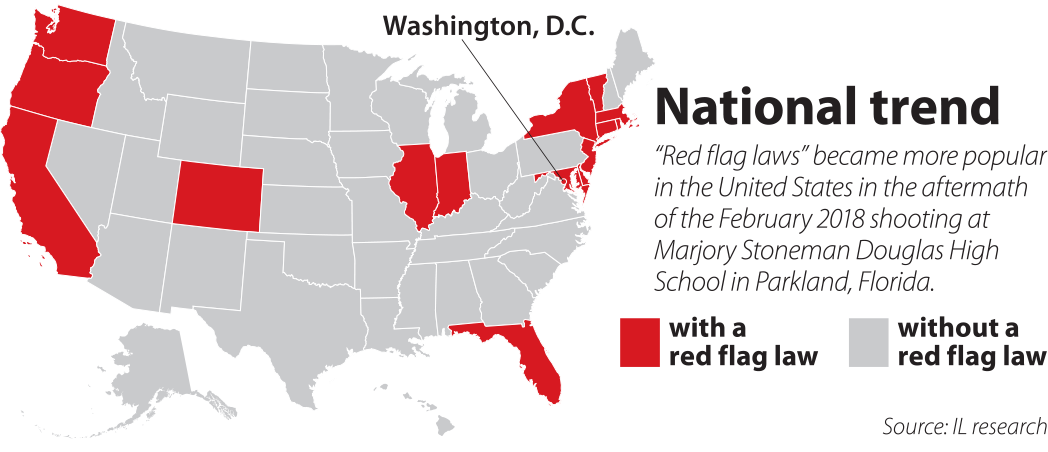

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn the aftermath of the February 2018 shooting at Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School in Parkland, Florida, legislatures across the country turned to the same gun policy to prevent mass shootings in their own states. Known as “red flag” or “extreme risk” laws, more than a dozen states have now enacted legislation designed to keep firearms out of the hands of those who are “dangerous.”

Indiana is considered a leader in the red flag law movement, as the Hoosier state passed its own version of the legislation more than a decade before the Parkland shooting. But with language that some experts considered overly broad and potentially unconstitutional, the Indiana General Assembly revisited that legislation, known as the Jake Laird Law, during the 2019 legislative session.

The result was an amended Hoosier red flag law aiming to protect due process while ensuring those who are a threat cannot access firearms. The bill, which became House Enrolled Act 1651, received bipartisan support among Hoosier lawmakers.

The result was an amended Hoosier red flag law aiming to protect due process while ensuring those who are a threat cannot access firearms. The bill, which became House Enrolled Act 1651, received bipartisan support among Hoosier lawmakers.

Gun rights advocates have raised concerns about red flag laws and their possible infringement on Second Amendment rights. But supporters say the bills that are being passed across the country are passing constitutional muster and are proven to save lives.

Leading from the heart

Codified at Indiana Code section 35-47-14, Indiana’s Jake Laird Law was enacted in 2005 in response to the fatal shooting of Indianapolis Police Officer Jake Laird in 2004. Laird was killed in the line of duty by Kenneth Anderson, who suffered from severe mental illness.

Relford

RelfordPolice had taken Anderson’s weapons from him prior to the shooting because of his mental health problems, but because he had not been convicted of a crime at that time, they had no choice but to restore his guns to him upon his release from treatment.

The original red flag law was written in direct response to that sequence of events, said Guy Relford, an Indianapolis-area attorney known as “The Gun Guy.” Law enforcement wanted a way to keep guns out of the hands of high-risk individuals like Anderson, so language allowing the removal of weapons from “dangerous” persons was drafted.

But opining that the 2005 General Assembly wrote the Jake Laird Law more with their hearts than with their heads, Relford said the original legislation was overly broad and, from his perspective, unconstitutional. The bill defined a “dangerous” person as someone who “may present a risk of personal injury to the individual or to another individual in the future,” and who “is the subject of documented evidence that would give rise to a reasonable belief that the individual has a propensity for violent or emotionally unstable conduct.”

Powell

Powell“‘May present a risk of personal injury in the future’ — that could apply to every human being on the planet,” Relford said, adding that it is difficult to define “emotionally unstable.”

Filling the gaps

Relford raised a constitutional challenge to the original language in 2013, but the Indiana Court of Appeals rejected his arguments, brought under Article 1, Sections 21 and 23 of the Indiana Constitution and the Fifth Amendment, in its decision in Redington v. State, 992 N.E.2d 823 (Ind. Ct. App. 2013), trans. denied.

Then after Parkland, legislatures began looking to the Jake Laird Law as a model of red flag law legislation. Dave Powell, executive director of the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council, said he has received requests for copies of Indiana’s statute from his counterparts in multiple states wanting to use the Hoosier law as the foundation for their own red flag bills.

That spotlight on Indiana’s law — one of only five in place before Parkland — made the shortcomings in the Jake Laird Law more evident, said Rep. Donna Schaibley, the Carmel Republican who authored HEA 1651. One of the biggest issues Schaibley wanted to address was the ability of “dangerous” people to obtain firearms after they are determined to be a threat.

“That was a little bit of a gap in our law,” Schaibley said. “…We don’t want individuals who are dangerous to have access to firearms if they have mental stresses.”

Schaibley

SchaibleyTo fill that gap, HEA 1651 makes it a Class A misdemeanor for a person who is found to be dangerous to knowingly or intentionally possess a firearm. Further, a person who knowingly or intentionally provides a firearm to a statutorily dangerous person commits a Level 5 felony.

But Powell noted that before HEA 1651, there was no way for gun dealers to know if a person was statutorily prohibited from having a gun. The law deals with that information gap by requiring court clerks to report a “dangerous” determination to NICS, the National Instant Criminal Background Check System, which is accessible by gun dealers.

Constitutional concerns

Relford agreed the General Assembly needed to address the access “dangerous” individuals have to firearms, but his primary concern was the language that defined what it means to be dangerous. Though his constitutional challenge in Redington did not succeed, he still believed the statute was overly broad.

Thus, he worked with Schaibley to redefine “dangerous” as a situation in which “(i)t is probable that the individual will present a risk of personal injury… .” Requiring a “probability” of risk inherently requires actual proof of a future threat, Relford said, rather than a blanket possibility that someone might become a threat at some point.

Additionally, the language regarding “emotionally unstable” people was reworked to include individuals who are “the subject of documented evidence that would give rise to a reasonable belief that the individual has a propensity for violent or suicidal conduct.”

According to Schaibley, statistics show that more than half of all people whose guns have been removed pursuant to the Jake Laird Law have been suicidal, but not a threat to others. Thus, replacing “emotionally unstable” with “suicidal” puts the law’s focus in the appropriate place, she said.

Sufficient due process?

Nico Bocour, the state legislative director for gun reform organization Giffords, said extreme risk laws nationwide are receiving bipartisan support. Even so, gun rights organizations have raised concerns about whether the laws provide appropriate due process and go far enough to protect Second Amendment rights, Bocour said.

Bocour

BocourRelford likewise noted the individuals subjected to red flag law confiscations have not actually been committed of a crime. Thus, their gun rights should only be limited while they are actually a threat.

To that end, HEA 1651 inserts due process language into the existing law, including a requirement that police file an affidavit supporting a seizure within 48 hours. If there is not probable cause to support the seizure, law enforcement must now return the firearms within five days of the court’s order.

If a “dangerous” individual petitions for the return of their weapons before one year has passed, he or she has the burden to prove they are no longer dangerous. However, if more than a year has passed, that burden shifts to the state to prove the individual is still dangerous. Additionally, during the time the weapons are held, the law now requires law enforcement to use “reasonable care” in storing the guns.

Courts have repeatedly upheld extreme risk laws, Bocour said, and data has shown the laws have, in many instances, averted legitimate threats. To that end, she expects bipartisan support to continue growing for such legislation, despite the due process concerns that have been raised.

Gov. Eric Holcomb signed HEA 1651 into law May 6, and the emergency act took effect immediately.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.