Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen Tippecanoe County Prosecutor Patrick Harrington used to visit law schools, he would have upwards of 10 ready-to-graduate students wanting to interview for jobs in his office. Now he might have two or maybe four students who are interested, and sometimes they confess they are talking to him only to practice their interviewing skills.

Harrington does not fault the students and the new lawyers who do not want to work in a prosecutor’s office. However, he said he is frustrated at what he sees as an escalation of the inability to recruit and retain attorneys.

“We need to have talented attorneys to do this work,” Harrington said. “It’s the most challenging work you can do.”

A look at the help wanted ads on the websites of both the Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council and the Indiana Public Defender Commission show many open positions in large and small county offices as well as state agencies. Most are entry-level jobs that do not require any previous experience beyond having a J.D. degree along with a license to practice in the state and being in good standing with the Indiana Supreme Court.

The increased difficulty that prosecutors and public defenders are having in finding attorneys is believed to reflect a shortage of lawyers in Indiana. About a decade out from the Great Recession — when law schools were criticized for oversaturating the job market— the situation, at least for the public sector in Indiana, appears to have gone in reverse.

During testimony before the Interim Study Committee on Corrections and Criminal Code in August, the Public Defender Commission highlighted the shortage.

“We are way understaffed in terms of attorneys for the state,” Andrew Cullen, the commission’s public polic and communications director, told the committee. “There used to be a time where we always thought we had too many attorneys. We are not there anymore.”

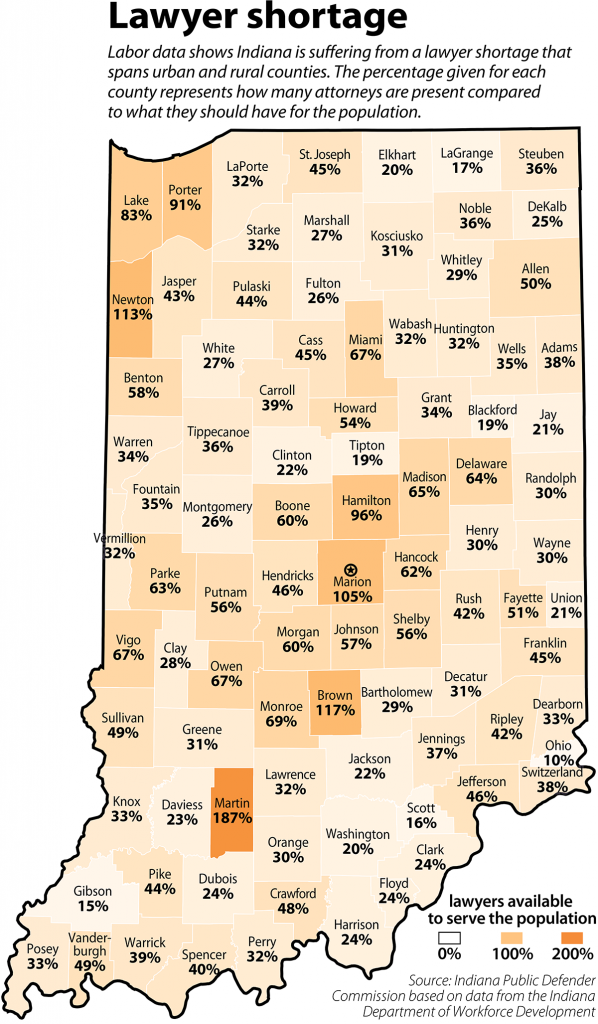

The commission reviewed occupational data from the Indiana Department of Workforce Development and found the state has a “far lower level of attorneys in the workforce in comparison to the nation,” according to Torrin Liddell, the commission’s research and statistics analyst. On average, the data indicate Indiana has just 36% of the recommended numer of attorneys per capita relative to the national average.

Harrington said he sees the shortage as increasing the possibility for mistakes.

Talking to a group of students at Indiana University Maurer School of Law, he was asked about wrongful convictions. Harrington replied that when prosecutor’s offices are fully staffed with highly trained attorneys doing their jobs correctly, the cases that lead to innocent people being incarcerated do not get filed. With enough attorneys, the offices are able to investigate, review the evidence and filter out the questionable cases, he said.

Causes and consequences

Of Indiana’s 92 counties, just four meet the 100% threshold, indicating they have enough attorneys to handle the legal needs of their residents, according to the Public Defender Commission. Liddell cautioned that the data may be faulty for counties with smaller populations that are showing more than ample attorneys, such as Brown and Martin, which register at 117% and 187%, respectively.

Also, he noted, the needs of each county are different. Some may be well-served by less than 100% of the national average while others might require more.

“But I can say with pretty good certainty that 36% is not enough,” Liddell said.

While the shortage cannot be linked to a single cause, both Liddell and Harrington pointed to two probable sources: declining law school enrollment and low compensation.

The total number of students matriculating has fallen by more than 150 over the last decade at IU Maurer as well as Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law, according to the American Bar Association. Also, while the enrollment at Notre Dame Law School has remained within the 500- to 600-student range, the entering classes in the past two years have each had roughly 50 fewer students than the 2019 first-year class.

Compounding the decrease is the closure of Valparaiso Law School in 2020.

Salaries for public sector lawyers have traditionally been lower than their counterparts in law firms, but prosecutors and public defenders contend new lawyers are facing even more difficulty stretching their paychecks, especially if they have student loan debt and are married with children. Moreover, while government attorneys usually get a nominal raise every year, private practice attorneys can get large boosts in pay plus bonuses.

Compensation surveys from the National Association for Law Placement illuminates the disparity. The national median prosecutor and public defender entry level salary was $56,200 and $58,300, respectively, in 2018. Comparatively, attorneys in the private sector in 2017 were making $58,000 at the smallest firms and $180,000 at the largest firms.

Some suggest the public sector could attract more law school graduates by offering a student loan forgiveness initiative that is more robust and less bureaucratic than the current federal program. In addition, they believe law schools could help stir interest by cultivating externships in county prosecutor and public defender offices so students could get an understanding of what the work entails.

To Cullen, the consequences of doing nothing to address the shortage could potentially lead to a less safe society. The criminal justice system relies on dedicated, well-trained public defenders who are not overworked, he said. If the offices are not fully staffed, jails could become overcrowded and justice will not be quick and efficient.

Change in attitude

IU McKinney has charted an uptick in the number of graduating students entering the public sector. The amount has grown from 55 in the class of 2017 to 68 in the class of 2020.

Whittley Pike, senior associate director of professional development at the law school, attributes the interest in government work to the state agencies being near the school and having open entry-level positions. Also, the alumni who work in the public sector often interact with students.

As the students prepare to graduate and enter the workforce, Pike will have conversations with them about public versus private sector salaries and how the pay compares to the workload and expectations of the jobs. Another aspect they talk about is the trial work experience that comes with employment in prosecutor and public defender offices.

Students will reconsider their plans over the course of their studies for what they want to do with their J.D. degrees, which Pike said is a natural part of their learning experience. How many IU McKinney graduates make a career in the public sector is uncertain, but Pike has seen a lot of students who, rather than thinking long-term, are trying to evaluate what is in front of them.

“I’ve certainly seen people who are just very excited about the public interest work that they’re going to do and they really believe in the change that they feel like they can make in their community,” she said. “I also have students who say, ‘I’m so happy I have a solid offer for now and I don’t have to worry about what I’m going to do in the next couple of years. It gets me closer to my long-term goal of private practice.’”

Retention is also a problem.

Allen County Prosecutor Karen Richards said her office is “woefully understaffed,” but what she really needs are lawyers experienced in putting together and presenting cases. The workloads are getting heavier because crime is up, and the amount of evidence to sift through has increased from police reports and photographs to social media posts, cellphone data and body camera video.

“This is a tough job,” Richards said. “It’s not for everybody, and finding those few people that it’s a good fit for is not easy.”

The Allen County office is focused on cultivating its own crop of experienced attorneys. Currently, the office has a group of 30-year-old lawyers who have been working there and, Richards said, are “really, really coming along nicely.” The opportunity to try cases is a key incentive, but the office also tries to foster loyalty by covering continuing legal education training, mentoring young attorneys and offering social activities.

Yet, in recruiting new lawyers who can be nurtured into seasoned deputy prosecutors, Richards said she has been noticing a change in attitude that may make retention even more difficult.

“I think they’re interested in money. I think they’re interested in amount of time they have to work,” Richards said. “… I think young people are much less willing to put their private lives on hold for their work life. That may be good, that may be bad, but that doesn’t always fit with the way it works around here.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.