Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe dispute over judicial elections versus merit selection in Indiana’s most populous — and diverse — counties isn’t new, but it is ongoing.

Right now, the debate seems to be centered on Lake County, the state’s second-largest county both in terms of overall population and in terms of non-white population.

Since 2021, litigation has been ongoing to switch Lake County to judicial elections, as is done in 89 of the state’s 92 counties. There are also legislative efforts to do the same.

But most recently, a federal judge granted summary judgment to state defendants in the lawsuit alleging the county’s judicial selection system violates Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act. The legislative efforts aren’t faring much better, although it’s difficult to get an answer as to why.

Regardless, proponents of judicial elections say they are committed to the cause.

The arguments

The case in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Indiana — City of Hammond, et al. v. Lake County Judicial Nominating Commission, et al., 2:21-cv-160 — was initiated by Hammond Mayor Thomas McDermott and a local voter, Eduardo Fontanez. State Sen. Lonnie Randolph, an East Chicago Democrat, later joined the case as a plaintiff.

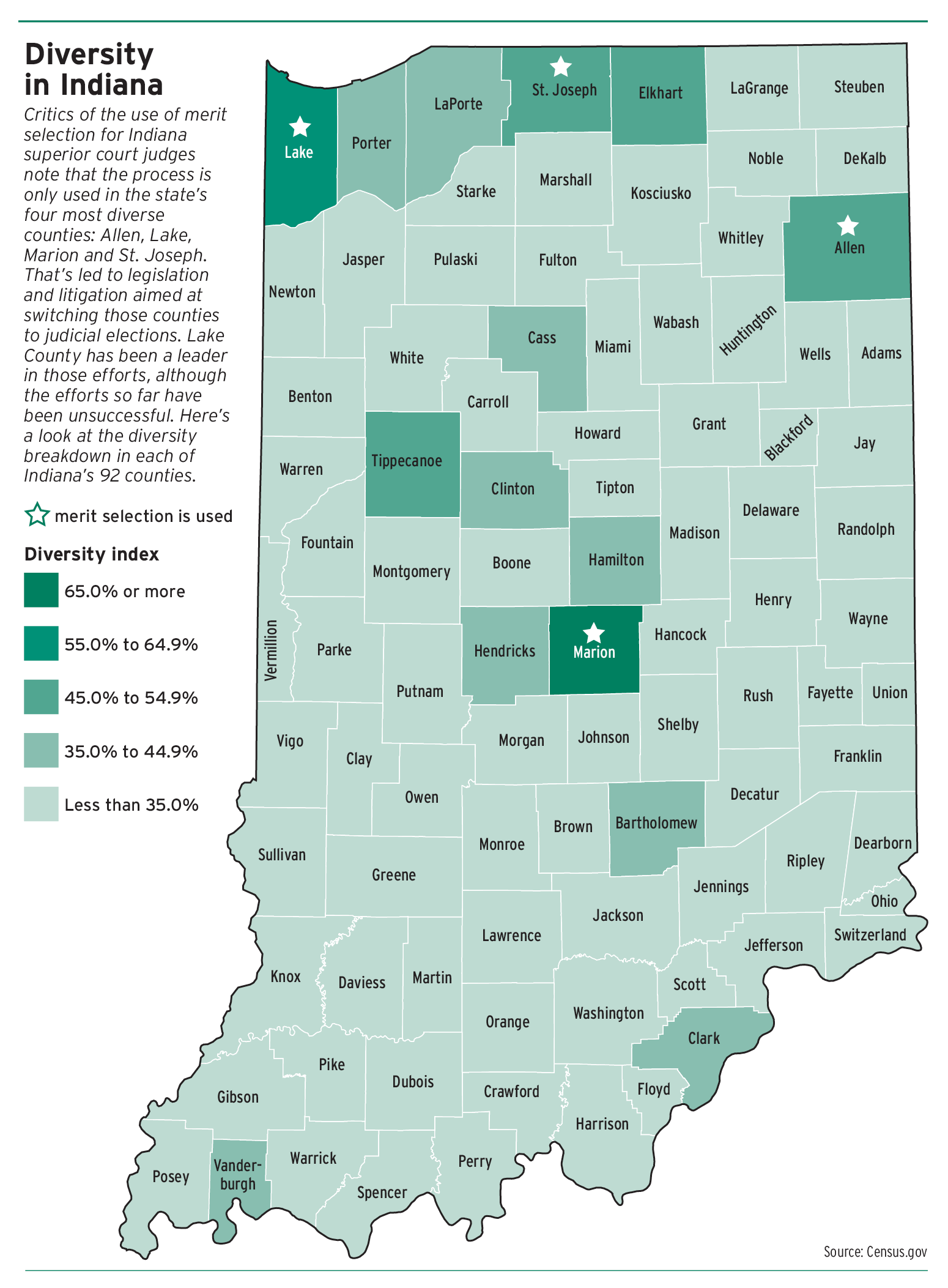

Their complaint, which was amended twice, alleged violations of the federal Voting Rights Act as well as the Indiana Constitution. Their argument is that voters in Lake County — as well as Marion and St. Joseph counties — are disenfranchised because they don’t get to elect their superior court judges.

In those three counties — as well as in Allen County, though only in cases of a vacancy — superior court judges are selected first by going through an interview process with the local judicial nominating commission, which selects finalists. Those finalists are then sent to the governor, who makes the final selection. Then, the selected judges periodically appear on the ballot for retention votes.

In all other Indiana counties, superior court judges are elected.

The plaintiffs allege that system is an act of voter discrimination because it is only used in Indiana’s most diverse counties.

But in court documents, the state asserted, “For over a century, Indiana’s judges at all levels were selected by Hoosiers through partisan elections. This system led to criticism regarding impartiality, judicial independence, and the continued ability to select high quality trial judges.”

Further, a 1972 study found, “The majority of Lake County attorneys and judges … interviewed were dissatisfied with partisan election of judges in Lake County, which … contributed to an attorney-managed administration of justice, unequal caseloads among Lake County judges, inconsistent application of Indiana’s trial rules, and an excessive number of cases being sent by Lake County judges to venues in outside counties,” according to the affidavit of Jerold A. Bonnet, general counsel in the Indiana Secretary of State’s Office.

“A merit selection process is essential in a highly populated and highly diverse jurisdiction like Lake County to provide safeguards for limiting political influence in Lake County superior courts,” Bonnet’s affidavit said.

Bonnet’s affidavit was cited multiple times in Judge Philip P. Simon’s ruling granting summary judgment to the state defendants — though not necessarily in a positive way.

“Let’s not beat around the bush: the reference to ‘diversity’ is a not so subtle reference to race,” Simon opined. “The State thus appears to acknowledge that the ‘diversity’ of Lake County, meaning the significant presence of racial minorities among its electorate, is a reason that superior court judges are not chosen by election but by a merit selection process instead. In the language of §2 (of the Voting Rights Act), the State of Indiana has imposed a procedure on Lake County that denies its citizens the right to vote for superior court judges on account of race or color.”

But that wasn’t the end of the analysis.

While the plaintiffs relied on Brnovich v. Democratic National Committee, 594 U.S. 141 S. Ct. 231, to support their claim of a VRA violation, the state argued, ultimately successfully, that Quinn v. Illinois, 887 F.3d 322 (7th Cir. 2018), is controlling. Quinn upheld the practice of allowing the mayor of Chicago to appoint the members of the Chicago School Board, rather than ruling that those members should be elected.

While Simon agreed that Quinn controlled, he did so with obvious reluctance.

“With respect, I find the Seventh Circuit’s reasoning in Quinn, and the case which it cites, to be unsatisfying, especially in light of Brnovich … ,” he wrote. “Nonetheless, Quinn is controlling law and I am not free to disregard it where it plainly applies.”

Hammond Mayor McDermott, speaking with Indiana Lawyer in January, said the plaintiffs were actually encouraged by Simon’s comments, even if his ruling was ultimately against them.

A common misconception about the litigation, McDermott said, is that his goal is to get rid of merit selection.

“In reality, my goal is to just be treated like the rest of the state,” he told Indiana Lawyer. “If that means the whole state goes to merit selection, if that’s what’s decided, God bless them.”

IL reached out to spokespeople for the Attorney General’s Office — which represented the state and secretary of state — after Simon’s ruling was handed down but received no response.

Legislative efforts

The courts aren’t the only place Sen. Randolph has been advocating for a switch to judicial elections in his county.

This year, he authored Senate Bill 25, which would mandate election of Lake Superior Court judges — the seventh year in a row he has introduced such legislation, according to his office.

Each year, the legislation has died without a hearing.

Speaking to Indiana Lawyer, Randolph said he has never been able to get answers to two questions: why his judicial election bills don’t get hearings, and why only select counties are mandated to use merit selection.

“What’s that little saying? ‘If there’s smoke, there’s a chance for fire somewhere,’” Randolph said.

This year’s SB 25 was assigned to the Senate Elections Committee, which is chaired by Sen. Mike Gaskill, R-Pendleton. Indiana Lawyer reached out to Gaskill for comment on why the legislation was not given a hearing this year or in years past but did not get a response.

Three years ago, the predicate for the lawsuit came in the form of House Enrolled Act 1453, which changed the composition of the judicial nominating commissions in Lake and St. Joseph counties.

That bill — authored by Rep. Mike Aylesworth, R-Hebron — mandated that the JNCs be comprised of seven members each, with three appointed by the governor, three appointed by the county commissioners and one Indiana Supreme Court justice.

At least one member of each JNC must be an attorney, whereas before, multiple attorney members were mandated.

Also, before, attorneys were able to elect or appoint JNC members.

When HEA 1453 was introduced in 2021, Aylesworth described the bill as a “simple reset” based on feedback he’d received from local lawyers who felt the judicial selection processes in Lake and St. Joseph counties were unfair and politically biased.

IL requested an interview with Aylesworth to discuss whether those attorneys were happier with the changes made under HEA 1453, but the lawmaker did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

What’s next?

An appeal of Simon’s order was docketed in the 7th Circuit on Jan. 29 as Case No. 24-1125. No other substantive filings had been docketed at IL deadline.

While the plaintiffs are hopeful that the 7th Circuit will use their case to revisit Quinn, McDermott said they are in it for the long haul regardless.

“The four counties with the highest African American concentration are treated discriminatorily, and that’s not acceptable,” McDermott said. “We’re going to keep on pushing, and if that requires us to go to the Supreme Court, we’ll keep pushing.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.