Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn hindsight, attorneys say, the footnote in the brief to the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals filed by the Health & Hospital Corporation of Marion County provided the clue for what has since come.

The original lawsuit was brought on behalf of the now-deceased Gorgi Talevski, an elderly dementia patient in northwest Indiana who, according to the complaint, had been chemically restrained and mistreated in a care facility owned by HHC. Specifically, the complaint sought to remedy Talevski’s situation by using 42 U.S.C. § 1983 to enforce the rights listed in the Federal Nursing Home Reform Act.

After the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Indiana dismissed the case, Arnold & Porter stepped in to represent the Talevski family pro bono and filed an appeal to the 7th Circuit.

HHC, in response, hired Washington, D.C., attorney Lawrence Robbins of Friedman Kaplan. He has argued 19 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and more than 60 before various U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals, according to his biography.

HHC, in response, hired Washington, D.C., attorney Lawrence Robbins of Friedman Kaplan. He has argued 19 cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and more than 60 before various U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals, according to his biography.

The brief Robbins and his colleagues filed with the Chicago-based appellate court included a footnote that broached what many contend is settled law.

Courts have for decades upheld an implied right that individuals can bring lawsuits under Section 1983 to enforce spending clause statutes like Medicaid. The footnote, however, questioned whether Section 1983 provides a private right of action because when it was passed in 1870s, contract law did not permit a third-party beneficiary to sue to enforce the terms.

“Although HHC recognizes that those arguments are foreclosed by the Supreme Court and Seventh Circuit precedent,” the footnote stated, “we believe a majority of the current Supreme Court might reach a different result if it were to revisit this issue.”

The 7th Circuit reversed the dismissal, and HHC turned to the Supreme Court.

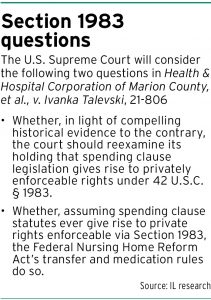

In its petition for a writ of certiorari, HHC elevated the footnote into its statement and broadened the scope of the legal arguments. Namely, the petitioner asked the court to reexamine its precedent around privately enforceable rights under Section 1983.

Since the Supreme Court granted cert in HHC, et al. v. Talevski, 21-806, organizations and individuals across the country have submitted briefs urging the justices to follow precedent and keep the private right of action.

“It would be devastating for vulnerable individuals if the petitioners’ wishes are granted,” Daniel Hatcher, Fort Wayne native and University of Baltimore School of Law professor, said. “By no longer having any additional federal cause of action, it makes it even harder for them to support their rights. And it would give a green light to state agencies to mimic what Indiana has done … to use vulnerable residents as a source of funds while they’re languishing in poor care while stripping them of federal protections.”

Poverty revenue

Hatcher, a former attorney at what is now Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath LLP, filed briefs critical of HHC at both the 7th Circuit and the Supreme Court.

Citing investigative reporting by The Indianapolis Star, Hatcher asserted the government agency has been purchasing for-profit nursing homes across the state and leveraging those facilities to significantly increase federal matching funds from the Medicaid program. In turn, he wrote in his SCOTUS brief, HHC has facilities “consistently rated as some of the worst in the country,” while shifting money to unrelated projects.

Hatcher called the money from the HHC scheme “poverty revenue.”

Hatcher called the money from the HHC scheme “poverty revenue.”

“They’re using the most vulnerable as a source of generating and maximizing revenue from the federal government and then misusing those funds,” Hatcher told Indiana Lawyer. If the Supreme Court rules in favor of HHC, “it would open the door for further misuse of federal funding streams and it would cause increased harm to the vulnerable resident and severely reduce their causes of action.”

HHC did not grant Indiana Lawyer’s request for an interview. However, in its petition to the Supreme Court, HHC stated Section 1983 lawsuits have burdened state and local governments with litigation costs and hefty damages.

“In reaching its erroneous result,” HHC asserted, “the Seventh Circuit in one fell swoop federalized medical malpractice law for patients in nursing facilities throughout its jurisdiction, sweeping aside carefully chosen state policies in favor of a one-size-fits-all resort to Section 1983.”

Widespread harm

Supporters of Talevski are concerned about the ripple effect of a possible adverse ruling. Abolishing the implied right, they say, will harm beneficiaries of Medicaid and other programs because those individuals will lose their ability to litigate.

Echoing other lawyers, Melissa Keyes, executive director of Indiana Disability Rights, acknowledged preparing and litigating such a case would take resources and skills that the vulnerable might not ordinarily have. Even so, access to the courts is an important enforcement tool, especially because the agencies running the program often do not have the ability to police all the organizations receiving the funds.

“I’m not saying that these are all slam-dunk cases and it’s the Wild, Wild West of 1983 cases getting approved by the courts,” Keyes said. “… I think it allows for some more impartiality, another review, to make sure that the state’s doing what it’s supposed to be doing with the money that Congress has given it to run that program.”

Indiana Attorney General Todd Rokita’s office filed a brief supporting HHC and in a statement argued against the implied rights.

“When individual beneficiaries bring unauthorized lawsuits to enforce federal grant conditions, they invite unelected federal judges to interfere with how state and federal officials carry out the jobs the public expects them to perform,” Rokita wrote. “The proper functioning of democracy requires that such judicial interference not occur unless Congress has expressly authorized it.”

Seeing an opportunity

The questions posed by HHC will not be new to the Supreme Court.

Sarah Somers, managing attorney for the North Carolina office of the National Health Law Program, said the legal theory curtailing private enforcement of Section 1983 has been bubbling and developing among conservative judges and scholars for 20 years.

A case from Louisiana, Gee v. Planned Parenthood of Gulf Coast, Inc., attempted to get the Section 1983 issue before the Supreme Court in 2018. The petition for cert was denied, but Justices Clarence Thomas, Samuel Alito and Neil Gorsuch dissented.

Adding to the familiarity is a precedent-setting case, Gonzaga University v. Doe, 536 U.S. 273 (2002). The lawyer arguing in that case against enforcement of statutes under Section 1983 was John Roberts, who is now the chief justice of the U.S. Supreme Court.

Somers speculated the supporters of HHC would like fewer requirements on how they spend federal dollars or are against spending clause programs and do not want private individuals to have enforcement rights.

“It’s been a long time in the making and all the dominoes are kind of falling,” Somers said. “We are optimistic. We think the briefs are terrific supporting enforcement, but we are concerned because we can see who’s on the court.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.