Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA 44-year-old federal law championed as a means of preserving Native American culture by preventing the removal of children from their homes and tribes is being challenged on constitutionality grounds — and the U.S. Supreme Court has agreed to hear it.

Justices at the nation’s highest court agreed on Feb. 28 to review the case of Brackeen, et al. v. Haaland, et al., 21-380, which centers on whether American Indians should receive preference in adoptions and foster placements of American Indian children.

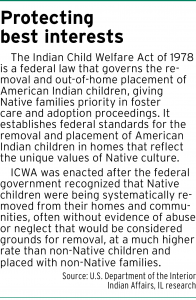

Taking center stage of the debate is the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978, or ICWA, a law enacted in efforts to rectify the mass removal of American Indian children from their families and placement in non-native foster and adoptive homes.

According to the U.S. Department of the Interior Indian Affairs, state and private adoption agencies removed as many as 25% to 35% of American Indian children from their homes in 1978. Of those, 85% were placed outside their families and communities even when fit and willing relatives were available.

Opponents of ICWA say the measure, among other things, is discriminatory for imposing “race-based” restrictions on foster care and adoption, which may not be in the child’s best interest.

American Indian leaders and tribes, however, consider the measure the “gold standard of child welfare practice.”

The Brackeens

U.S. Supreme Court justices agreed to hear Brackeen, consolidated with three other cases that target ICWA as unconstitutional. The arguments stem from a Texas couple who, in trying to adopt their foster child, ran into a roadblock with the child’s tribe.

Plaintiffs Chad and Jennifer Brackeen started adoption proceedings with the support of their foster child’s biological parents, but the child’s tribe had the right to intervene because the minor was identified as an “Indian child” under ICWA.

The law defines an “Indian child” as “any unmarried person who is under age 18” who is either a member or citizen of an American Indian tribe or is eligible for membership, or citizenship in a tribe and is the biological child of a member/citizen of a tribe.

The Navajo Nation notified the state court it had located a potential alternative placement for the Brackeens’ foster child with nonrelatives in New Mexico.

The Navajo Nation notified the state court it had located a potential alternative placement for the Brackeens’ foster child with nonrelatives in New Mexico.

The Brackeens argued that good cause existed to depart from ICWA’s preference for placing the child with an American Indian family because, among other things, the biological parents supported the Brackeens’ adoption petition.

A Texas court denied the Brackeens’ adoption petition in August 2017. They argued in a subsequent federal suit that ICWA violated the equal protection and due process clauses of the Constitution. The Brackeens were joined by states including Texas, Louisiana and Indiana, which all argued ICWA violated the guarantees of states’ rights as provided by the 10th Amendment.

The U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Texas ruled for the plaintiffs, but the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals reversed in August 2019. It held, in part, that ICWA’s definition of “Indian child” was not a race-based classification but a political classification subject to rational basis review.

The case then fractured the full 5th Circuit on rehearing as it struck down certain provisions of ICWA in an April 2021 decision. The en banc court splintered in a complex 325-page decision that ultimately concluded Congress had the authority to enact ICWA but that some of its provisions were unconstitutional.

“The en banc Fifth Circuit’s fractured opinion shows that legal uncertainty permeates child-custody proceedings under ICWA,” the Brackeen petitioners wrote in their cert petition. “Only this Court can definitively resolve what law applies to ‘Indian’ children— ICWA, or an individualized consideration of the child’s best interests under state law.”

Where it stands

Arguments in the case will take place during the high court’s next term and will feature two main questions:

• Whether ICWA’s placement preferences — which disfavor non-American Indian adoptive families in child placement proceedings involving an “Indian child” and thereby disadvantage those children — discriminate on the basis of race in violation of the U.S. Constitution.

• Whether ICWA’s placement preferences exceed Congress’ Article I authority by invading the arena of child placement — the “virtually exclusive province of the States” — and otherwise commandeering state courts and state agencies to carry out a federal child placement program.

Hoover Hull Turner LLP attorney Che’lee John, a citizen of the Diné, said that although ICWA has been challenged numerous times on the basis of an improper classification, the Supreme Court has continually affirmed that the relationship between the federal government and American Indian tribes is not based on race and ethnicity.

“And that comes from the trust and treaty relationship that the federal government has had with tribes since time immemorial and even predating the United States,” John said.

“That has always been the purview of the federal government — that it is the federal government who is the non-American Indian entity that is responsible for working within kind of regulating tribes, not states or individual parties,” John continued. “And because of that, I don’t suspect that the argument based on equal protection will be successful, just because that has been long standing.”

Indianapolis attorney Travis Lovett, a member of the Echota Tribe of Cherokee Indians, said Brackeen is yet another case layered on top of a decade of debates concerning ICWA.

“That debate typically hinges on arguments concerning fairness, race and what is best for the child. But you’ll seldom hear the debate hinging on procedural process or tribal sovereignty,” Lovett said.

The measure is not about fairness or race, he opined, but rather about following civil procedure as set forth by Congress to prevent the eradication of American Indian culture via the adoption of American Indian children by non-American Indian families.

When Lovett read the argument that giving preference to American Indian families and foster homes violates equal protection rights under the Constitution, he scratched his head in confusion.

Citing Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974), Lovett said the Supreme Court has already held that Indian preference is permissible because it stems from the trust relationship between the federal government and Indian tribes.

“Congress, through its plenary power over Indian affairs, has spoken and set forth a process that must be followed,” Lovett said, “regardless of personal opinions underpinning the ICWA.”

Protecting culture

Dan Lewerenz, a staff attorney for the Native American Rights Foundation, said American Indian Country is largely united in supporting ICWA.

“This is telling,” said Lewerenz, who is a member of the Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska. “The plaintiffs seem to think of themselves as being advocates for the best interests of Indian children. But you can tell by the alignment of Native people in the case that the plaintiffs think they know better than Native people do, because the entirety of American Indian Country is arrayed against the plaintiffs in this case.”

Indiana, which joined the litigation early on, did not file or join a cert petition before the U.S. Supreme Court. The Indiana Attorney General’s Office was unavailable to comment on the case or its stance on issue.

John said there is some concern of “slipping back” to the era of mass removal of American Indian children in assimilation efforts.

“But I think that right now, it’s pretty speculative,” she said. “And I think that there’s a lot of non-American Indian support for these regulations.”

In Lovett’s opinion, the challenge underpinning the Brackeen case “poses disruption and threatens Congress’ well-established intent to preserve Indian culture by keeping Indians, Indian.”

“The culture does not sustain itself,” Lovett said. “Indian people themselves must keep the culture, which is achieved by handing it down generation by generation.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.