Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe Now

When Sen. Karen Tallian, D-Ogden Dunes, resigned in the middle of her term from the Indiana General Assembly in November 2021, she actively recruited another attorney to take her place.

The solo practitioner served in the Senate for 16 years and said she wanted a lawyer as a replacement because of the benefit attorneys bring to the legislative process.

Looking at a photo of the lawyer-legislators taken her first year in the Statehouse, she noted the need for the statutory knowledge attorneys bring, particularly in committees on the judiciary and corrections and criminal law.

“I don’t think it’s going to get rid of partisanship,” Tallian said of adding more lawyers to the Legislature. “I think it would add to the general understanding and knowledge base.”

Tallian’s seat has been filled by an attorney, Rodney Pol Jr., and while the number of lawyer-legislators in the Indiana legislative body has not changed, it remains low.

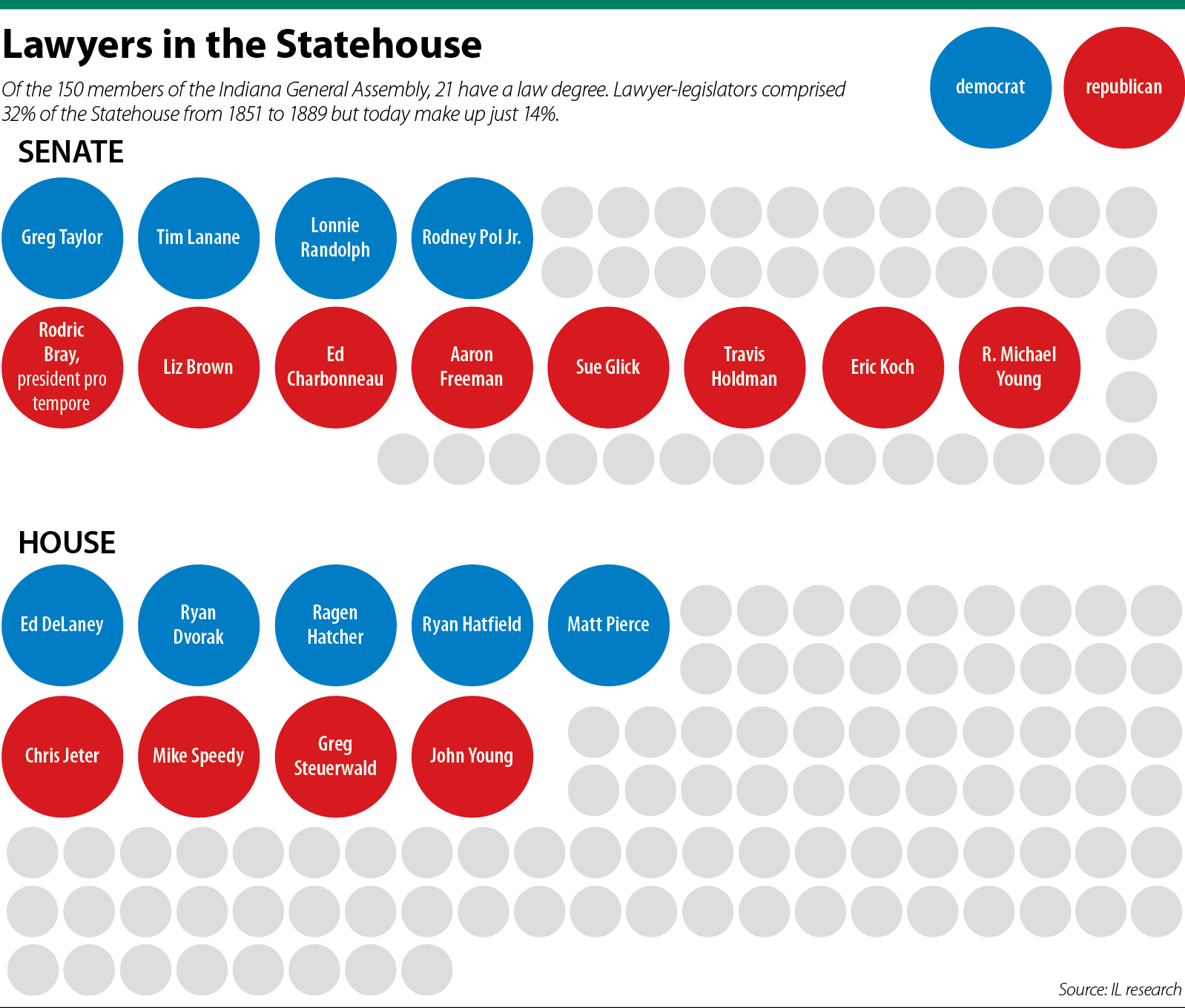

As the General Assembly reconvenes, just 21 of the 150 members — or 14% — have a J.D. degree. Comparatively, from 1851 to 1889, when individuals became lawyers by reading the law, 32% of the Legislature was comprised of attorneys, according to “The Centennial History of the Indiana General Assembly, 1816-1978” by Justin E. Walsh.

Indiana has a part-time citizen Legislature, so different backgrounds and experiences are vital to ensure the interests of all Hoosiers are represented. Currently the House and Senate includes medical professionals, small business owners, consultants, educators, real estate brokers, financial advisers, funeral directors and farmers.

Former Speaker Brian Bosma, who served 34 years in the General Assembly, said having members from different walks of life is critical because they can offer their unique perspectives while the laws are being crafted. However, practicing attorneys are especially beneficial to the process.

“They bring to the process a more intimate knowledge of the statutes that the General Assembly is dealing with; they’ve had to apply them in many cases to real-life situations where people may be in distress over one matter or another,” Bosma said. “They see that very practical application of the Legislature’s work on Hoosiers.”

Examining every word

The legal knowledge lawyers bring to the Legislature, Tallian explained, can stir some frustration among their nonattorney colleagues. Attorneys will dig into the minutiae of proposed bills and look for conflicts with other statutes, which can be tedious and, in the former senator’s case, would cause other legislators to exclaim, “Tallian, are you picking at words again?”

Tallian would continue undeterred. There were times when she would find the language in the draft gave the bill a different meaning or would have a different impact than intened by the authors.

Tallian would continue undeterred. There were times when she would find the language in the draft gave the bill a different meaning or would have a different impact than intened by the authors.

“I have always tried to explain bills in common language,” Tallian said. “I always try to translate those concepts into the most understandable language. (But) you can’t write it that way because then you’re going to go to court and argue every single word. So it has to be written precisely.”

An example of the need for precision came when the General Assembly waded into the issue of medicinal marijuana in 2017. House Enrolled Act 1148, which drew wide bipartisan support, created a limited exception for the use of substances containing cannabidiol for patients who suffered from treatment-resistant epilepsy.

However, about six months after the bill was signed into law, then-Indiana Attorney General Curtis Hill issued an opinion highlighting conflicts between the new law and other sections of the code. He concluded that although the law allowed for the use and possession of CBD, it did not provide a regulatory scheme for the manufacture, distribution and sale of cannabidiol substances.

The attorney general said he was sympathetic to what the law was trying to address and acknowledged cannabidiol has been considered by some to cure numerous afflictions.

“One hopes, for the sake of those who are suffering any of these maladies, that it can be so,” Hill wrote in his official opinion on HEA 1148. “But hoping and wishing are not the proper role of government. Our job is to place our fellow citizens on notice about what the laws passed by their representatives really mean.”

Sen. Sue Glick, R-LaGrange, a former prosecutor-turned-solo practitioner joined the Legislature in 2010. Like Tallian, she emphasized the skills lawyer-legislators have in being able to read and think critically about statutes and proposed statutory revisions that come every session.

Glick keeps a copy of the Indiana Code book on her desk so she can explain problems or inconsistencies with bills to her nonlawyer colleagues. She has seen confusion on the faces of some of the members who are nonlawyers when the lawyer-legislators delve into the details of a bill.

Yet, Glick pointed out, the laws passed through the Statehouse will be interpreted by the courts, so the wording has to be clear.

“We were trained to look at all the various interpretations,” Glick said of lawyer-legislators when they look at the ways the bill could be interpreted and whether it will do what the drafters intended. “That’s something a lot of people don’t understand. They say, ‘Well, it’s the law, there’s no choice in the matter.’ … That’s what we really get involved with, and the minutiae is difficult for some people to understand.”

Impacting Hoosiers’ lives

Since joining the Legislature in 2018, Rep. Ragen Hatcher, D-Gary, has paid particular attention to the language in bills as well as to the contradictions the measures could have with other parts of the Indiana Code. Like Glick, she noted the courts will be carefully reading and interpreting the laws crafted by the Legislature so she wants to be catch the potential problem areas.

An attorney and former member of the Gary City Council, Hatcher said she is well aware of how the actions of the Legislature impact Hoosiers. When bills are filed that tweak or clarify a provision of a law passed in a previous session, she sees the time and resources someone may have wasted because the wording was not right the first time.

“Those are the things that I find myself really looking for when I’m reading things because every time we have to come back and correct it, it means that somebody has gone through the process, either in court or in some form of litigation and then gotten caught up by the statute,” Hatcher said. “I try to read them as thoroughly as possible to try to interpret the language, how it could be interpreted later.”

Mark Palmer was a lawyer-legislator for a handful of terms in the 1980s, and he has since returned to the Statehouse as a lobbyist with his own company, Market & Capitol Advocacy, LLC.

Palmer said he does not miss being a member of the House, but he does enjoy the times when he sees the lawyers in the General Assembly pull out their code books and begin dissecting a bill. To him, that is the process of lawyers making better legislation for Hoosiers.

“About 95% of the bills that go through the Legislature aren’t really political. Somebody is trying to solve an issue at home or an issue that the state needs addressed,” Palmer said. “So (the lawyer-legislators) have these very robust debates … in terms of what a definition means or a code section means or how to tie it into other code sections. Those are the things that serve as a comprehensive knowledge or comprehensive experience that, I think, other legislators often rely on in making their judgment about things.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.