Subscriber Benefit

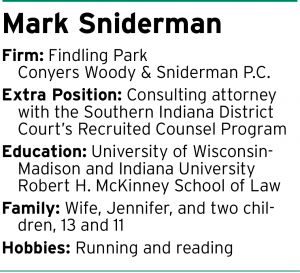

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWhen filing litigation, attorney Mark Sniderman lets the client tell the story.

The partner at Findling Park Conyers Woody & Sniderman in Indianapolis has increasingly shifted his practice to handling Section 1983 civil rights claims, usually on behalf of clients who may otherwise have no voice. He has been part of the legal teams that fought for marriage equality, voting rights and LGBTQ rights. Also, he has represented numerous inmates in lawsuits filed against state and federal correction officials.

Typically, the litigation begins with Sniderman settling in front of a computer to draft the complaint. The resulting document is clear and clean, free of heated language, hyperbole and jargon, because he knows this could be the client’s only chance to explain to the court what happened.

“Especially in the context of prisoner litigation … you might lose on summary judgment and never get to trial. You might lose on a motion to dismiss,” Sniderman said. “A person’s got a story to tell and this might be the only way to tell it officially. So let’s tell it, let’s tell the story in the complaint.”

Sniderman is taking that respect for the client’s story to his new role as consulting attorney for the United States District Court for the Southern District of Indiana’s Recruited Counsel Program. He will continue his private practice and serve in this new position, which started Feb. 1, on an as-needed basis, providing materials and offering guidance to attorneys in the program.

Lawyers who participate in the Recruited Counsel Program generally represent inmates whose complaints have survived a motion to dismiss. At the annual recognition breakfast that was held every year prior to COVID-19, the volunteer attorneys would speak about how much they learned, especially because many did not have much experience with civil rights cases or working with prisoners, and how rewarding the experience was.

The program was started in 2016 to help the Southern Indiana District Court handle the flood of prisoner litigation. Of the 3,116 civil cases filed from Dec. 1, 2020, to Nov. 30, 2021, in the Indianapolis-based federal court, 21%, or 660, were pro se prisoner civil rights cases, according to data provided by the Indiana Southern District Court.

Since the program’s inception, it has appointed attorneys for 499 cases. Sniderman has handled six of those.

Indiana Southern District Court Chief Judge Tanya Walton Pratt said Sniderman has the right mix of experience and skills for the new position.

“I think he’s going to be excellent,” Pratt said. “… When he interviewed (for the position), we could see he realizes how important and helpful it is to have an experienced lawyer to reach out to recruited counsel to advise.”

The chief judge noted Sniderman worked with James Chapman, an Illinois attorney who served as the consulting attorney for the Southern Indiana District Court until his death in 2021. Also, he has handled civil rights litigation along with medical malpractice and Eighth Amendment cases. Plus, he is “very committed to the fair representation” of the litigants.

“So we think he is just going to be a wonderful mentor to our pro bono attorneys,” Pratt said. “… He’ll be able to help lawyers with even the simple questions like, ‘How do I go to the prison and visit my client?’”

Two sides

Sniderman’s own journey to becoming a lawyer includes a flirtation with politics in his California home and a turn as the assistant coach of the men’s rowing team at his alma mater, the University of Wisconsin. He came to Indianapolis to become the national team programs manager for USRowing.

Along the way, he had friends who went to law school and, in the Circle City, he was impressed by the attorneys who were involved in matters like disputes over doping and team selection as the rowers prepared for the 2000 summer Olympics in Sydney. Finally, at age 33, Sniderman enrolled at the University of California Hastings College of Law before transferring to Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law.

seriously. (IL photo/Marilyn Odendahl)

Sniderman credits his classmates for inspiring him with their idealism, and he credits attorneys Terry Park and Stephen Caplin with giving him the courage to start his own practice before the ink was dry on his J.D. degree.

The first lawsuit he filed was against General Motors over an airbag that had injured a woman.

“It was eye-opening,” Sniderman said. “(I learned) the law is important and the facts are equally important. When you really get into the facts, you can represent your client well even against large corporations.”

When recounting his former cases and talking of the matters he has argued in court, Sniderman is always deferential and respectful of the lawyers and clients on the opposite side. Particularly with inmate litigation, he noted the problem is not Department of Correction personnel but rather is rooted in prisons turning into places where society tries to fix or ignore its inequities.

When recounting his former cases and talking of the matters he has argued in court, Sniderman is always deferential and respectful of the lawyers and clients on the opposite side. Particularly with inmate litigation, he noted the problem is not Department of Correction personnel but rather is rooted in prisons turning into places where society tries to fix or ignore its inequities.

“The older I get, the longer I practice, this is frustrating, but there’s always at least two sides to every case,” Sniderman said. “There are really talented and well-meaning people on all sides. It’s deeply important for me to remember that and to listen to the other side. It helps everybody.”

Robert Katz, professor at IU McKinney, witnessed how Sniderman listened and coaxed the opposing side to tell its story when he joined his former student-turned-friend in a class action against the DOC. The case, Stafford, et al. v. Carter, et al., 1:17-cv-289, pushed Indiana into providing prisoners with what is essentially a cure for hepatitis C.

Prior to the treatment, individuals with the blood disease had to suffer under a range of symptoms, but a new pill taken once a day for 12 weeks rid the body of the virus. Sniderman and Katz were part of a nationwide effort to force the states to offer the then-new standard of care to its prison population.

Katz remembered Sniderman deposing witnesses by asking a question, then asking it again and again, each time in a slightly different way. The purpose was to get a deep understanding of how medical care is given to the incarcerated. Then he was able to present the facts and convince the judge to rule for the plaintiffs.

“He’s the best attorney I’ve ever worked with,” Katz said. “Working with him has made me a better lawyer and, frankly, a better person. He’s demonstrated how someone can pursue their ideals through the law.”

Speaking of that case, Sniderman recited the names of the three named plaintiffs and highlighted that they repeatedly put the class’s best interest above their own in a way he had not seen before. The men had a story, and Sniderman made sure they could tell it.

“There’s value in telling the story,” Sniderman said. “I try to keep that in mind especially in prisoner cases. (The complaint) might be it. Let’s make a record of it. Win, lose or draw, let’s get it out there.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.