Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowNo one ever wants to remove a child from their parents’ household.

When there are allegations of abuse or neglect in a home, child welfare officials, caseworkers and judges have to make tough, complicated decisions about what is ultimately best for the child, said Rep. Ryan Lauer, R-Columbus, a member of the Indiana House of Representatives’ Family, Children and Human Affairs Committee and author of several bills designed to protect children.

When there are allegations of abuse or neglect in a home, child welfare officials, caseworkers and judges have to make tough, complicated decisions about what is ultimately best for the child, said Rep. Ryan Lauer, R-Columbus, a member of the Indiana House of Representatives’ Family, Children and Human Affairs Committee and author of several bills designed to protect children.

Lauer said the legislative, judicial and executive branches of government, including the state’s Department of Child Services, work hard to figure a balance between respecting people’s constitutional rights as parents and protecting children when they are in an abusive environment.

“There’s obviously a point where the state needs to be involved. That has to be balanced with parental rights,” Lauer said.

Still, some parents who have been investigated by DCS, whether in Indiana or other states, would like to see more oversight of the child removal process.

For example, in one high-profile case in Massachusetts, Sarah Perkins and Joshua Sabey’s children were removed from their home in the middle of the night after child welfare officials in that state responded to a call from a hospital about one of the children’s rib fracture.

It took Perkins and Sabey four weeks to reunite with their children.

Caleb Kruckenberg, an attorney with the nonprofit Pacific Legal Foundation, is now representing the Massachusetts couple in a parental rights case spurred by the removal.

According to Kruckenberg, a doctor found the rib fracture, which had healed and was believed to have happened accidentally when the couple’s son was removed from a car seat.

“It was really news to everyone,” Kruckenberg told Indiana Lawyer.

Kruckenberg said the Massachusetts Department of Children and Families investigated for a week and the couple were led to believe nothing was wrong.

Then DCF officials showed up at 1 a.m. on a Saturday morning with police and took the children from the home.

After finally reuniting with their children, the couple filed their federal lawsuit for compensatory and punitive damages against individual social workers, police officers and the city of Waltham, Massachusetts.

Kruckenberg said he and his clients want the lawsuit to put a spotlight on the processes states are using for emergency removals and what he believes is a lack of judicial oversight in those cases.

“Suddenly it’s put on the parents to justify the return of their children,” he said.

Indiana examples

Tom Blessing, a partner with Fishers-based Massillamany Jeter & Carson LLP, recently handled a case similar to the one in Massachusetts.

In that case, Blessing represented Adam Huff and his wife, Laura Hope Huff, in a child removal case involving the Indiana Department of Child Services.

DCS reached a $1.375 million settlement earlier this year with the Indianapolis couple after the Huffs filed a federal lawsuit and alleged the department violated their constitutional rights when it wrongfully took their two children from their home.

The Huffs filed their lawsuit in 2020 in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana against DCS, a DCS supervisor and two DCS case managers.

Blessing said a family member made a report that one of his clients had abused one of their kids. He said DCS initially told his clients everything was fine.

“My clients assumed that was the end of it,” Blessing said.

But then, Blessing said, DCS came back out to the Huffs’ home later that week. A DCS case manager allowed the children to stay at the home as long as the father wasn’t there.

He said a judge issued a detention order, putting the kids into a shelter.

“They didn’t have a lawyer (yet). They weren’t allowed to ask questions, things we usually associate with due process,” Blessing said.

A few months later, and a few days before a child in need of services factfinding hearing, DCS dismissed all charges against the Huffs. The children were returned to their home after having spent about four months in DCS custody.

“The whole experience was a nightmare for the family,” Blessing said.

Blessing said he thinks there needs to be fundamental changes in training for DCS workers, adding that there are likely lawyers in the Indiana Attorney General’s Office who could provide that training.

The announcement of the Huffs’ settlement came about six weeks before the parents of a child who was removed by DCS for three months as an infant reached a $750,000 settlement with the agency.

In an email to Indiana Lawyer, Brian Heinemann, Indiana DCS deputy director of communications, declined an interview and also declined comment on both settlements.

The process

Heinemann gave Indiana Lawyer the guidelines and rules DCS staff members must follow in a removal situation, what they’re trained to look for and how the removal process works.

According to the guidelines, DCS will remove a child from a parent, guardian or custodian if the following situations occur:

• A reasonable person would believe the child’s physical or mental condition is seriously impaired or seriously endangered due to injury by the act or omission of the child’s parent, guardian or custodian, or

• The child’s physical or mental condition is seriously impaired or seriously endangered as a result of the inability, refusal or neglect of the child’s parent, guardian or custodian to supply the child with necessary food, clothing, shelter, medical care, education or supervision, and

• The coercive intervention of the court is needed to protect the child.

When it is determined an involuntary removal of a child is necessary, the DCS family case manager will:

• Obtain supervisory approval prior to removal of any child from their parent, guardian or custodian.

• Determine if there are any barriers to communication with the parent, guardian or custodian and take necessary action to make appropriate, reasonable accommodations.

• Obtain a court order authorizing the removal unless emergency removal is necessary to protect the immediate health and safety of the child.

• Request a law enforcement agency presence at the removal. DCS will not remove a child without law enforcement present, unless an emergency removal is necessary.

Legislative efforts

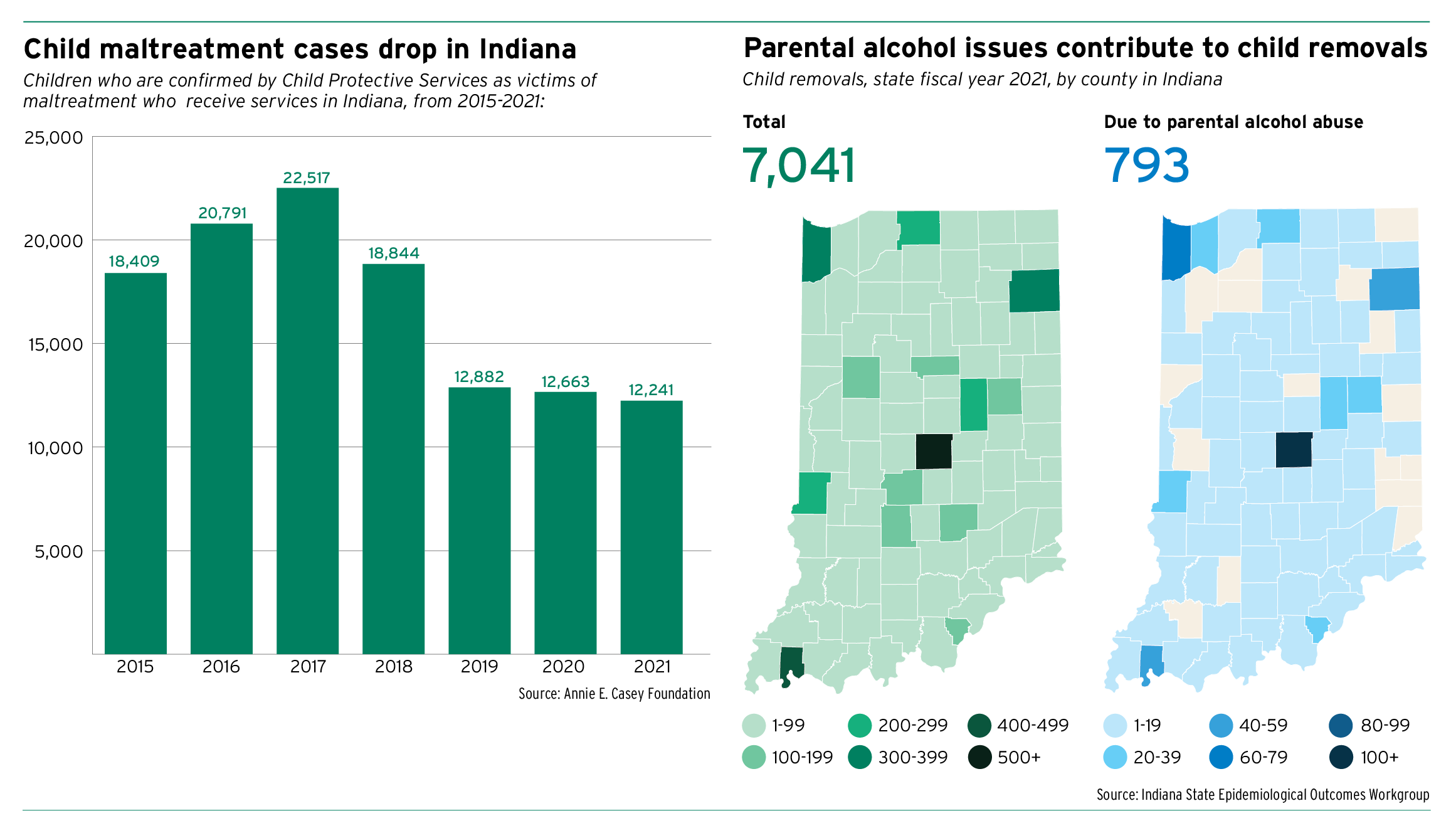

A total of 60 Indiana children died from neglect or abuse in 2021, according to the 2021 Annual Report of Child Abuse & Neglect Fatalities in Indiana.

Of those 60, 38 children died from neglect and 22 from abuse, the report said.

In 2022, Rep. Lauer authored House Enrolled Act 1247, requiring additional data to be collected for the report, including whether the child had any history with DCS and whether abuse or neglect was substantiated.

Lauer has also introduced pieces of child placement legislation, including a bill that tried to shorten the length of time to permanency in terms of getting foster children into adoption.

The representative said he would continue to work as a legislator to protect children.

In any case involving DCS, he said, there’s a natural tension when minor children are involved.

“Every case is an individual case,” Lauer said. “Sometimes it’s hard to lift up the veil in cases with jaw-

dropping issues.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.