Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIndiana’s growing attorney shortage is becoming more acute in rural areas, as new lawyers tend to locate in larger cities.

The Indiana Supreme Court and the Indiana State Bar Association are taking big and small steps to help bridge the gap, from making more people eligible to take Indiana’s bar exam to studying the root causes of a shortage that could lead to a lack of access to the legal system.

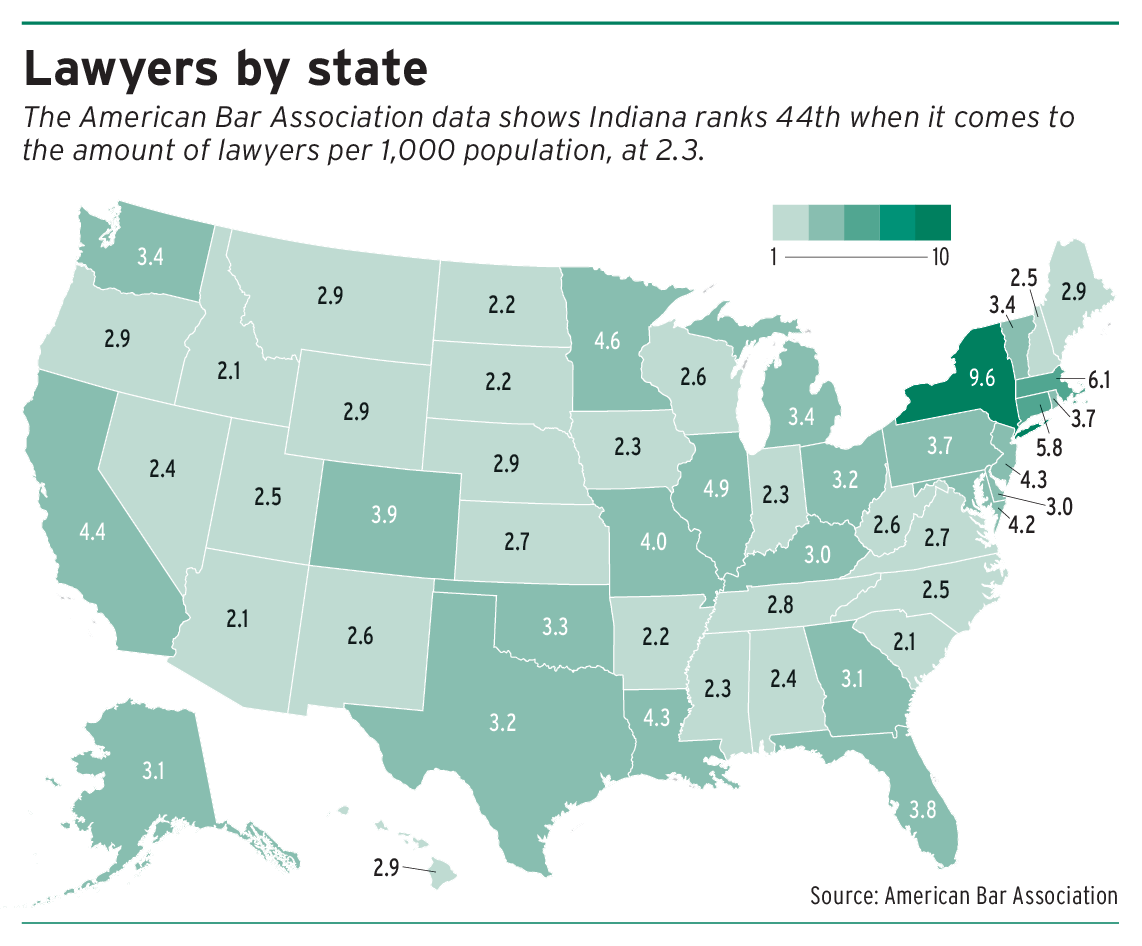

Indiana ranks among the lowest states in the nation in terms of the number of attorneys per capita.

According to the 2023 American Bar Association Profile of the Legal Profession, Indiana has the 44th lowest number of attorneys per capita at only 2.3 per 1,000 residents.

The lowest number reported among the states is 2.1 lawyers per 1,000 in Idaho, Arizona and South Carolina.

But the shortage is much more severe in some rural counties, especially as a steady stream of baby boomers retire.

In southeastern Indiana, for example, the number of attorneys in Dearborn County is 95% below the national average–the lowest in the state.

Fast-growing Hamilton County in the Indianapolis suburbs ranks the highest at 62% above the national average.

Implementing change

A recent change to increase the number of Indiana lawyers that has received the most attention is the allowance of graduates of non-ABA-accredited law schools to petition to take the state bar.

But the state’s high court also decided last month to allow applicants who completed their legal education outside the U.S. and obtained a graduate degree from an ABA-approved law school in a program based on American law to petition to take the state bar exam.

Indiana Board of Law Examiners Executive Director Brad Skolnik said that change for international students promises to be significant.

“One thing we do see is that there are a number of graduates from the three Indiana law schools, who are foreign educated, who will now possibly be able to be admitted in Indiana,” Skolnik said. “A number of them bring some skills and talents, they may speak a foreign language or whatever. So they may be able to help the community, certain underserved communities, too.”

He said he’s not sure how long it will take to go through every new petition, but hopes to move as quickly as possible with the requests and make sure that potential applicants are informed on a timely basis.

Skolnik also noted that each application will go through the same level of care and scrutiny as other applications.

“They will still then be subject to the same level of scrutiny in terms of character and fitness, passing the [Multistate Professional Responsibility Exam], as well as achieving a successful score on the bar exam,” Skolnik said.

Applicants requesting a waiver, if approved, would be able to take the February 2025 Indiana bar exam.

Another change coming this year will allow the bar admission ceremony to be held in April rather than May, allowing newly-minted lawyers to get an earlier start on entering their profession.

Skolnik said he often hears from prosecutors and public defenders who say they need new attorneys to start right away.

“Unfortunately, there’s nothing we can do, but now we’re addressing that. So they can get that person on board and working three weeks earlier,” Skolnik said. “I think that’s a really positive thing.”

Skolnik said another pressure point is the increasing difficulty in assuring that he has lawyers to serve as fitness and character interviewers for the bar in every county in the state.

“We’re already beginning to feel the pinch in terms of there being fewer lawyers practicing in rural communities,” Skolnik said. “When our character and fitness interviewers retire, there are not that many lawyers in the community left who could fill that position.”

Finding more solutions

ISBA President Tom Felts said his association plans to create three focus groups to study issues related to the access to the justice system.

The first group will look into broader pathways to admission and legal education.

Another group would consider legal models that could allow some people to offer certain types of legal assistance without being full-fledged attorneys.

A third group would examine the root causes of the lawyer shortage.

Felts said the groups are being established “because we think that we as an association of lawyers really are well suited to be able to really address what the practice of law is like in these areas and what lawyers can do to incentivize lawyers to move to these areas and help with the issues as they are presented to us.”

Justin Forkner, chief administrative officer for the Indiana Supreme Court, said the high court also is working to do more to get ahead of the issue before it becomes severe.

“The problem is that you get fewer younger lawyers coming in, and you have older lawyers retiring out,” Forkner said. “At some point that wave is going to crest and collapse over. If we haven’t put ourselves in a position to be ahead of it, I wouldn’t say we’re at a crisis point now. But there will be one.”

He said the high court is working on forming a group to explore the issue more deeply.

Forkner pointed to South Dakota as a possible example, noting that the state has a stipend model that it uses to incentivize lawyers to practice in rural areas.

“I think all those sorts of things will be on the table,” Forkner said.

He said conducting video proceedings via the internet also is a game changer that can allow an Indianapolis lawyer to more comfortably accept a case from one of the far-flung corners of the state.

Another option Forkner mentioned was a federal grant program that provides student loan repayment assistance for state and federal public defenders and local prosecutors who agree to remain employed in those fields for at least three years.

He said Indiana hasn’t participated in that program for several years but is considering it.

“We can focus that on rural county service in particular, so the courts working with the Public Defender Council, the Prosecuting Attorneys Council to figure out the best way to structure that and get that money out to lawyers who are really practicing in areas and in a field where we need them,” Forkner said. •

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.