Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAttorney Anthony Wagner sees the benefits of a booming economy when residents come to clear their financial debts.

Located in the Marshall County town of Bremen, Wagner, whose practice includes civil collections, said about half of those with past due obligations are either paying off the amount owed with one check or agreeing to an “aggressive payment amount.” He pointed to neighboring Elkhart County and its robust recreational vehicle industry as the reason for the flow of money into local consumers’ pockets.

Unemployment in the region is low, jobs are plentiful and wages are generous because of the strong demand for towables and motorhomes. In addition, northern Hoosiers, like many residents across Indiana, have gotten boosts from the government stimulus payments ,issued to buffer the negative impact of COVID-19, and the advances on the child tax credit.

Wagner said even the debtors who have their wages garnished do not always feel any pain, as their paychecks are hefty enough to absorb the punch.

However, the attorney also said he knows unexpected events and changes in circumstances can harm consumers regardless of how financially fit they are. He said he believes any downturn in employment in the region — whether an individual gets injured and is unable to work or the production lines slow and layoffs start — will quickly alter people’s ability to pay their bills.

“If the RV industry takes a hit, you would see a big spike in bankruptcies and collections,” he said.

Many Hoosiers are likely in the same precarious position of facing a debt collection if their paychecks get smaller or their bills get bigger.

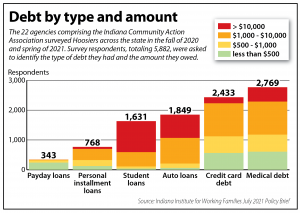

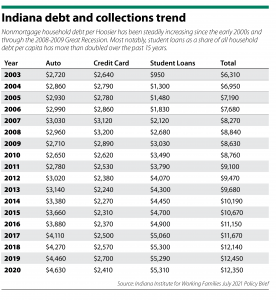

A July 2021 report by the Indiana Institute for Working Families found that from 2019 to 2020, debt levels in Indiana increased at a rate of 3.6%, which outpaced the national increase of 3.0%. In dollars, Indiana saw debt levels balloon by roughly $8 billion to $226.5 billion in 2020. This equates to $40,770 in household debt per Hoosier.

Andy Nielsen, senior policy analyst at the institute, noted a rising concern over what could be coming in 2022.

In response to the pandemic, the government implemented moratoriums and put a hold on payment obligations for things like mortgages and student loans. But those obligations are scheduled to return when the new year arrives.

Low- and moderate-income Hoosiers have been hit especially hard by the coronavirus-induced economic upheaval. Nielsen said households have been prioritizing what they are able to pay, with shelter, utilities and food usually at the top of the list. If another monetary stress, like a student loan payment, is tacked on, these households will have to make even more decisions about what they can pay.

“What we’re concerned about is how consumers are going to prioritize those things,” Nielsen said. “How they prioritize those payments is going to be a function, then, of what goes into the debt collection market.”

Legitimate debt

Legitimate debt

Banks, medical providers, car dealerships and other creditors have options for collecting debts. They can pursue payment themselves, turn the matter over to a debt collector to get the money for them or sell the bad paper to a debt buyer.

Also, unlike evictions, where landlords typically must file a petition with the court to remove a tenant, the process for getting a debt paid can happen without ever needing to involve the legal system. The holder of the debt can contact the consumer through a letter or phone call to try to collect.

Yet debt collections do share some commonalities with evictions — in particular, lopsided legal representation and few options for debtors.

A 2020 study of debt collectors’ impact on civil courts by the Pew Charitable Trusts found most plaintiffs in debt collection cases could afford to be represented by legal counsel, but consumers had an attorney in less than 10% of debt claims. This can open the collection defendants to undue harm, because Pew’s analysis showed the debtors with a lawyer were more likely to secure a settlement or win the case outright.

Robert Duff, an attorney with the Indiana Consumer Law Group, estimated his office is averaging two to three calls a day from consumers who are facing a debt collection. Often, the callers say they only learned they had been sued for a debt when they were notified of a proceeding supplemental being initiated in order to collect on a default judgment that had been entered against them.

In cases where a judgment has been entered, there may be little remedy a lawyer can offer. But according to Duff, prior to the judgment being issued, the debtor can push back by asking for proof that the debt is legitimate. Buyers will scoop up massive amounts of overdue accounts but do not always get the complete documentation that shows the consumer did incur the debt.

Duff said he believes debt buyers are being given a pass on the hearsay rules. Purchasers are being granted default judgments, and unless the consumer demands proof, the dockets are too full to ensure every claim has supporting evidence.

“Generally, it’s not the court’s job to police hearsay on its own; that’s the job of the opposing party,” Duff said, adding consumers would likely not know to object without an attorney. “But in the case of a default judgment, Rule 55(B) tasks the court with assessing the evidence to enable it to enter judgment. The sheer volume of defaults filed by debt collectors may make scrutinizing their evidence in each instance very difficult, but debt collectors should be held to the same standard any plaintiff would be.”

Solo practitioner Matthew Cree said he is seeing an increase in claims filed either outside of the statute of limitations or without proper documentation showing the plaintiff actually owns the debt.

Some of the individuals coming to Cree for legal help are facing collections from mortgage foreclosures that occurred during the Great Recession. As he explained, the properties were sold at sheriff sales for less than what was owed on the mortgage, so now as these families are more financially stable, they are getting billed for the deficiencies from the foreclosures, which he has seen reach $36,000 and $50,000.

Compounding the situation, debtholders are not always responding to debtors’ requests for proof. This is forcing consumers to go through the discovery process to make the plaintiffs show they have purchased the debt.

“Unfortunately, it is not illegal to file a claim” without proof of title or beyond the statute of limitations, Cree said. “It’s really up to the debtor and the debtor’s counsel to scrutinize the claim.”

Being represented

Creditors’ rights attorney Fred Pfenninger of Pfenninger & Associates has welcomed the transition to virtual hearings because more debtors are appearing at the proceedings and he is able to talk to them about clearing away the debt. He can find out where they are working, where they bank or just assess the potential for a payment plan.

“A lot of times, our biggest problem is we haven’t had any communication with them and we’re unable to discuss their finances and what they can pay or what they’re willing to pay to pay down the debt,” Pfenninger said.

Still, he said creditors generally want to move forward with getting a final order and wage garnishment from the court even if the debtor agrees to a payment plan. The debtholders, he explained, are trying to lower their risk of another creditor stepping in with a court order and intercepting the stream of income that would have enabled the consumer to pay off the first creditor.

Nielsen said he has seen the risk consumers face when they attempt to resolve their debt collection issues without an attorney or advocate. He has worked as a financial coach helping lower-income Hoosiers with their budget and debt problems.

Often, the consumers were having trouble communicating with the creditors. They would try to start a conversation, writing three or four times but getting no response. Or, if they did make contact, the creditor would not mention anything about settling the debt for less than what was owed.

Often, the consumers were having trouble communicating with the creditors. They would try to start a conversation, writing three or four times but getting no response. Or, if they did make contact, the creditor would not mention anything about settling the debt for less than what was owed.

That changed, Nielsen said, once he picked up the phone and the creditors realized someone else was paying attention. Just having an advocate, the consumers were able to get information about a payment plan and make a “better informed decision.”

Nielsen said he sees that the need for advocates and attorneys to help debtors is rising as consumer debt continues to grow and the deferments put in place at the start of the pandemic will be expiring soon. Some families will be fine, but he said he wonders if others have had enough time to catch up on their bills and prevent a crippling collection action.

“I think logic governs that if creditors are going to sue you,” Nielsen said, “they’re going to want full payment.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.