Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIndiana's legal community and child advocates say the state's juvenile justice system remains behind where it should be, but local efforts offer hope the system is heading in the right direction. However, getting around the current and all-too-familiar past state of affairs remains the largest obstacle.

"We're pretty much where we were," said Indianapolis attorney Terry Hall with Baker & Daniels, a court-appointed special advocate volunteer who also serves on the board of Kids' Voice of Indiana and an Indiana State Bar Association committee devoted to children's rights. "These juvenile justice issues ought to be on the front burner and are extremely important, but everyone's attention is often focused on problems that seem simpler to solve."

"We're pretty much where we were," said Indianapolis attorney Terry Hall with Baker & Daniels, a court-appointed special advocate volunteer who also serves on the board of Kids' Voice of Indiana and an Indiana State Bar Association committee devoted to children's rights. "These juvenile justice issues ought to be on the front burner and are extremely important, but everyone's attention is often focused on problems that seem simpler to solve."

Evidence of the Indiana system's flaws came to light forcefully in April 2006, when a study commissioned by the Indiana Juvenile Justice Task Force revealed the shocking depth of flaws in Indiana's juvenile justice system and how many kids don't have adequate access to counsel – half of youth routinely waived counsel and the rate was as high as 80 percent in some parts of the state.

Those on the front lines of the juvenile justice system say much still depends on the jurisdiction and whether money and resources exist to best help a child, in everything from public defense and representation to detention alternatives and incaration. They note that many successes exist, but those examples often get overlooked at the statewide level and consistency doesn't exist.

Still, the foundation is there and the legal community is as devoted as ever to build on those efforts already in place. As the state moves forward and looks at what other jurisdictions have done and are doing to reform their systems, Indiana is pushing to connect its scattered dots of local success even as it grapples with changes expected to alter key parts of the juvenile justice system in the coming year.

"Indiana has a long way to go in holistic training in juvenile training and ensuring performance standards of representation, to provide more uniform standards on the quality of representation kids can get," said Kim Brooks Tandy, a lawyer who serves as director of the Children's Law Center and was principal author of the 2006 assessment."First, a structure needs to be in place to create a will for change. These issues we've raised require a legislative response, but also a judicial and public defender response and help from bar associations. Someone has to move the train."

Connecting the dots

Judges, attorneys, and advocates at the local level are cautiously optimistic about where the state's juvenile system is heading, but all agree that the individual successes can be mirrored in other areas to help the entire system. They credit the Indiana Supreme Court in nurturing and encouraging innovation, as well as state and national groups that offer grants to pay for those programs.

For example, Marion County is being viewed as a model site for innovation with the creation of an initial hearing court. Juvenile Judge Marilyn Moores and her staff are working with the Annie E. Casey Foundation and a federal grant to find alternatives to detention and work to hit at the roots of juvenile crime.

Meanwhile, other counties are putting their own programs in place to help hit at the root of juvenile justice issues.

"You get some states that are controlling, but Indiana is like an incubator for juvenile justice innovations," Porter Juvenile Judge Mary Harper said. "It's fun, you get to be like an inventor."

Judge Harper is recognized statewide as one of those innovators, and her county's juvenile system has benefited from it. The judge, while proud that her county has as many juvenile public defenders as it does deputy prosecutors handling those types of cases, is most excited about the mental-health diversion program that the county helped establish and is now being used in various counties statewide.

Porter County's program started in 2005 and works to identify, treat, and track youth with mental illness and try to work them around the juvenile justice court system. It was modeled after a successful program in Pennsylvania that she'd first heard about at a summit the year before. She coordinated the project with the Indiana State Bar Association's Civil Rights of Children Committee, which remains involved and has helped establish this as a statewide model.

Federally funded with a grant through the Indiana Criminal Justice Institute, six counties are part of the project – Bartholomew, Clark, Johnson, Lake, Marion, and Porter counties; routine screening began for those counties' youth Jan. 1, 2008. The hope is to expand to five more counties by year's end.

Judge Harper sees this and other diversion programs the county offers as a way to help reform the system. She noted that it took seven years in Pennsylvania for 21 of that state's 23 detention centers to implement mental-health screening, so the progress so far can only be seen as a success.

Judge Harper sees this and other diversion programs the county offers as a way to help reform the system. She noted that it took seven years in Pennsylvania for 21 of that state's 23 detention centers to implement mental-health screening, so the progress so far can only be seen as a success.

"You can adjudicate a case, but you need to get relatively close to right and almost exactly identify the needs of the child," Judge Harper said. "There's more involved than litigating a case. At a minimum, if you can't keep a child from getting involved in the juvenile justice system and can't divert them successfully, you're a lot closer to a disposition by virtue of what's already done in that diversion program."

While not an exact result of the 2006 report, the mental-health diversion program is directly tied to the same issues and ultimately fit into what juvenile judges and the ISBA committee are working to improve.

While not an exact result of the 2006 report, the mental-health diversion program is directly tied to the same issues and ultimately fit into what juvenile judges and the ISBA committee are working to improve.

"Everything ties together when it comes to juvenile justice," said Amy Karozos, a staff attorney with the Youth Law T.E.A.M. of Indiana and former state public defender who currently chairs the ISBA Civil Rights of Children Committee. "They may not understand implications of what they're doing, but there's a big picture we're all somehow working toward and will eventually be able to see."

Aside from working on the juvenile mental-health screening project, the ISBA committee is also studying the access to counsel report and other initiatives statewide and hopes to connect the dots of these local efforts, Karozos said. It is also monitoring work and issues being considered by the Indiana Supreme Court's Juvenile Justice Improvement Committee, she said.

The committee is studying those issues and plans to make recommendations to county bar associations about better addressing those points, she said.

"We want to keep this issue of juvenile justice on everyone's mind," Karozos said. "There's no timeline. It's a continuing thing, seeing where opportunities for change are and trying to assist that change."

Reforming the system

Reforming the system

Indiana isn't alone, according to those at the national level, and some describe the entire public defense system for juveniles as shamefully inadequate. Jurisdictions are struggling with similar issues nationally, but Indiana can be viewed as further along than some because at least it has pieces of a funding system in place.

Statewide, juvenile judges are pressured by the increasing caseloads that mostly remain unexplained – such as the 30 percent increase in CHINS cases seen in Marion County the first four months of this year. The state saw about a 19 percent increase in new juvenile filings from 1997 to 2007 and the steady increases are mirrored at the local level, though funding typically decreases and the local excitement about innovative improvements can be limited by reality.

To make necessary reforms, a state needs to have the legislative, political, and financial support in place, according to Tandy. Indiana hasn't yet reached that point.

Last year, the General Assembly failed to pass legislation that would have changed juveniles' access to counsel and also prevented juveniles from making statements during mental-health screenings, assessments, and treatment as evidence in a delinquency hearing or adult-court hearing.

Those advocating change hope Indiana adopts methods used in other jurisdictions across the country, such as mandating juvenile representation or creating statewide offices to oversee juvenile public defense and reform.

Tandy and others are encouraged by findings in a local government-reform report released in December that included a push for a state-funded public defender system. While many of the recommendations weren't included in the current property-tax legislation, juvenile justice advocates are encouraged that the issue has at least been raised in the report entitled "Streamlining Local Government," which included the support of Chief Justice Randall T. Shepard, a co-author with former Gov. Joe Kernan.

That could lead to change in coming years, the chief justice and juvenile justice advocates say.

"We're getting better, but there's always room for improvement," Vanderburgh Juvenile Judge Brett Niemeier said.

Sooner, not later

But the philosophical talk of reform and exchange of ideas is now weighed down by coming changes from recently adopted legislation, which was part of a property-tax law passed by lawmakers and signed by the governor in March.

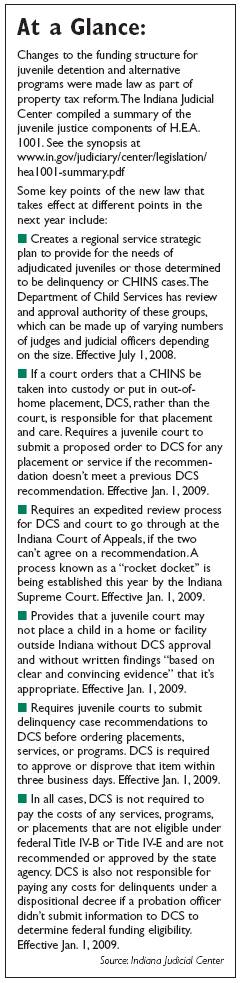

Effectively, House Enrolled Act 1001 shifts juvenile detention costs from the counties to the state and gives the Indiana Department of Child Services more oversight authority of juvenile delinquency, status, and child welfare cases. An expedited "rocket docket" appeals process is being established for the Indiana Court of Appeals, which will allow the DCS and trial courts to get a quick review of any decisions made if they don't agree. Most juvenile justice-related changes take effect in January 2009.

Juvenile judges, attorneys, and advocates are concerned about what the new law will mean for children in the system, while the law's proponents emphasize how this will expand Indiana's ability to collect federal reimbursements for a $440 million system and make the process more efficiently centralized through the state agency.

DCS Director James Payne, who presided over Marion Superior's Juvenile Court for about 20 years before Gov. Mitch Daniels appointed him to lead the agency in 2005, said the legal community has little to worry about.

"This isn't going to be as fearful as they're talking about," he said. "The fact is, courts can still do what the courts want to do under any interpretation. I don't think it ties (judges') hands, it just adds a review and evaluation component."

Payne emphasized that this legislation wasn't quickly thrown together; it was discussed extensively with judges, attorneys, probation, and service providers. He said the new law will present a more coordinated system for looking at what's best for families and children, and courts will have final say in all but the estimated less than 15 percent on which the DCS and courts don't agree.

Payne emphasized that this legislation wasn't quickly thrown together; it was discussed extensively with judges, attorneys, probation, and service providers. He said the new law will present a more coordinated system for looking at what's best for families and children, and courts will have final say in all but the estimated less than 15 percent on which the DCS and courts don't agree.

When asked about the agency's ability to handle the additional responsibility, the judge said: "Only time will tell."

But jurists have expressed concerns, questioning whether the state agency has the ability to handle this expanded role and whether funding for local programs that have been successful – such as diversion options – will remain available.

For instance, in Vanderburgh County, Juvenile Judge Niemeier said at least one of his programs could be in danger. He runs a school-release facility that's similar to an adult work-release program, offering about 12 beds for non-secured youth allowing them to travel back and forth to school or outpatient-treatment programs, the judge said. But it's not eligible for federal grants – a key component of H.E.A. 1001.

"We're wondering and speculating if it can continue," he said. "It's not enormous, but it keeps them local and provides for that need we have here."

Judge Niemeier also wonders about being able to continue using two case managers from a local counseling center, currently paid for by the DOC. They have about 10 kids each and that funding may go away, though the judge is prepared because the county recently hired a therapist for the court to rely on and that can accommodate the needs.

More significantly, the judge wonders what impact the state detention funding will have because DOC placement currently is being offered free to counties, but there will be tighter controls on options for treatment and detention alternatives.

"Judges may be more apt to send kids to the DOC to save money," he said. "I hope that's not the case, as this could result in shorter stays and I don't think that's in the best interest of kids or safety of communities."

Indiana now ranks fourth in the number of juveniles being sent to state facilities, according to a national report, "Geography Matters: Child well-being in the states," issued in April by the national child advocate group Every Child Matters Education Fund.

Allen Superior Judge Charles F. Pratt, who chairs the Juvenile Justice Improvement Committee, said this new law won't be much different than current practice as long as judges properly understand what's happening, and the committee must work to educate the bench and bar.

"This is a departure from practices we've had in the past, and so there's concerns that this would limit courts' discretion," Judge Pratt said. "But a close reading and knowing the underlying intent shows that there's enormous opportunity to create a partnership between juvenile courts and the DCS in a systematic way. There's been a barrier between these two systems, and if embraced properly this can create an opportunity to work together more efficiently for the benefit of children."

While much remains uncertain, those attorneys on the front lines point out that Indiana entities must work together on these new changes and always work toward meaningful reform, not just putting new laws on the books.

"What kind of reform do you want?" Karozos asked. "That's what everyone needs to be asking."

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.