Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIt was a tragedy that sent shockwaves through the federal judiciary.

The 20-year-old son of New Jersey Judge Esther Salas, Daniel, was gunned down in his own doorway in July. His father and the judge’s husband, Mark, also was shot, though he survived.

The gunman was Roy Den Hollander, a self-described “anti-feminist” lawyer who posed as a FedEx deliveryman to gain access to the home. Den Hollander later died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound, but the aftershocks of his attack reverberate.

“He was a lawyer — that’s another aspect of the tragedy that makes it troubling,” said Jane Magnus-Stinson, chief judge of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana.

Magnus-Stinson and other Hoosier federal jurists say they live daily with the reality of threats to their safety, though that reality usually seems distant. But when shootings like that at Salas’ home occur, the threat hits home.

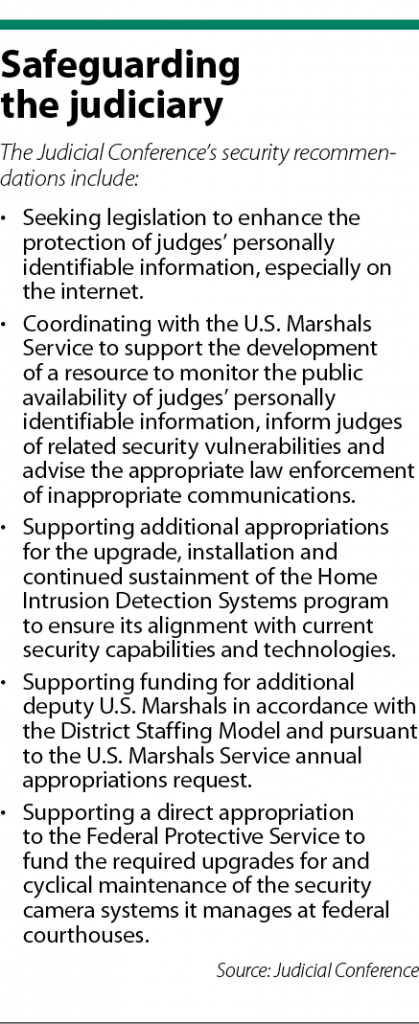

That’s why the federal Judicial Conference has adopted a series of recommendations aimed at improving the safety of the federal bench. The recommendations focus on protecting personally identifiable information in the digital age and ensuring adequate funding is allocated to the U.S. Marshals and other safety measures.

“While some of these recommendations are in response to the tragic attack on Judge Salas and her family, all are of critical importance and are long-standing issues of concern,” said David McKeague, judge of the 6th Circuit Court of Appeals and chair of the Judicial Conference’s Judicial Security Committee.

Taking it seriously

Northern District of Indiana Chief Judge Jon DeGuilio doesn’t like to discuss specific threats because he doesn’t want to give anyone any ideas. But he acknowledges that all judges — including state court judges — are aware that their work will anger people.

Indeed, Magnus-Stinson was a state court judge when she received a threat to herself and her family. The man likely had a mental illness, the chief judge said, and she theorized that he just wanted to go back to prison. Even so, she reported the threat to law enforcement, and now she’s part of a victim notification system that tells her when he’s released into the community.

That’s her motto any time she receives an alarming letter or other threat, Magnus-Stinson said — tell law enforcement. That way, even if a threat turns out to be benign, she’ll have done her due diligence to protect herself, her family and her colleagues.

The Marshals Service is tasked by law with protecting the federal judiciary, but Magnus-Stinson said the service is “woefully underfunded.” Courthouse exteriors are protected by the Federal Protective Service, while outside bollards, parking lot gates and other building safety features come from the General Services Administration.

All three of those agencies offer protection outside of Article III, McKeague said. To that end, the Judicial Conference’s recent funding requests for the Marshals Service and the Federal Protective Service underscore the dire need for additional judicial protection.

“The courts have never been involved in trying to ask for more money for other agencies,” he said. “This is very different from anything we have ever done.”

A new threat

A new threat

According to Michael Kanne, judge of the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals, federal judges are safest when they’re in a courthouse or federal building. Out in the community, they’re more vulnerable.

Kanne previously chaired the Judicial Security Committee, and during his time as chair, he worked with Congress to appropriate funds for a judicial home burglar alarm system. But according to McKeague, those systems are now outdated, which is why the conference has requested funding for an upgrade.

Today, there’s a new kind of threat to judges out there: the internet. DeGuilio noted that Den Hollander used online resources to find Salas’ home and plan his attack.

“The less information out there the better,” Kanne said. “But it’s very difficult. You can find out stuff about almost anybody online.”

When speaking on judicial security issues, Kanne has advised jurists not to create Facebook pages and even to keep photos of themselves off of the internet. Court personnel should take similar steps, he added.

Both DeGuilio and Magnus-Stinson agreed that cybersecurity should be a priority for judicial safety. But the challenge, DeGuilio said, is helping judges find the websites where their personally identifiable information is located.

Even if such data can be located, Kanne said getting it off the internet is its own challenge.

“I’m not sure how you go about doing it, because there’s the First Amendment you run up against,” he said. “But first of all, you have to start with judges and judicial personnel not voluntarily putting it out there.”

Staying vigilant

As the Judicial Conference begins its lobbying efforts for security reform, there are also efforts at the state level that could help ensure judicial safety.

Magnus-Stinson pointed to the Illinois Judicial Privacy Act, which prevents the release of the personally identifiable information of judges and their families. Under the law, judges can request that public agencies remove such information from the web. She expects there to be lobbying for similar legislation in Indiana soon.

Judges are generally vigilant about their self-protection, Magnus-Stinson said. But even so, more safety resources are always welcomed.

“We’re worried not just about ourselves. We’re worried about our families, we’re worried about our staff,” McKeague said. “We want to make sure we’re safe, but we also want to make sure our families are safe, so that they don’t pay the price of a job we swore to do to uphold the Constitution.”•

— Associated Press contributed to this report.

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.