Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowLeaders from all three branches of Indiana government rallied last month to discuss ongoing statewide efforts to address the growing mental health needs of Hoosiers — and to promote a new way of working together.

Roughly 1,000 attendees, representing each of Indiana’s 92 counties, gathered Oct. 21 for a mental health summit at the Indiana Convention Center in downtown Indianapolis.

Hosted by the Indiana Supreme Court, the summit offered a wide array of breakout sessions for discussion on issues related to mental health, crisis intervention teams, behavioral health clinics, trauma-informed care and more.

Indiana Chief Justice Loretta Rush gave remarks at the event, as did Justice Christopher Goff, Gov. Eric Holcomb, Lt. Gov. Suzanne Crouch, House Speaker Todd Huston, R-Fishers, and Senate President Pro Tem Rodric Bray, R-Martinsville.

This is a unique time in history, Rush told Indiana Lawyer. At the same time the suicide hotline 988 is rolling out nationwide, jails are packed with people who are experiencing a mental health crisis.

“Locking them up and having them locked up and then locked up and then locked up and locked up on these misdemeanors, we’ve got to do better,” Rush said. “You’ve got to divert them, and we’ve got to get the infrastructure in place.”

That means creating a targeted state infrastructure with three basic principles: someone to contact, someone to respond and a safe place to go for help.

With local justice reinvestment advisory councils, also known as JRACs, in place, judicial leaders at the summit emphasized that Indiana communities now have the chance to collaborate to accomplish meaningful work toward addressing the mental health crisis.

Rush pointed to the hundreds of professionals and stakeholders from across the criminal justice and behavioral health continuum present at the summit who were seeking solutions.

“People care about people in their communities with mental health (problems),” Rush said. “In this time where people seem to be fighting about everything, is this an issue we can get done?”

What is JRAC?

Joining forces and getting things done is exactly what Goff said he believes can, and will, happen when communities utilize the full benefits of their local JRACs, as well as the statewide JRAC, which he chairs.

JRAC stems from efforts at the national level to implement the Justice Reinvestment Initiative, which seeks to address the effects of decades of tough-on-crime policies by incarcerating fewer people and reinvesting the savings into local communities to address the root issues.

Indiana implemented its own version of JRI in 2015, calling it the State JRAC Statute. Its goal is to review and evaluate state and local justice systems and make recommendations regarding best practices and criminal justice funding awarded to local communities.

But the deinstitutionalization of low-level, nonviolent offenders at the state level presented challenges at the community level, Goff said. As such, strong local partnerships were encouraged through local JRACs.

Last year, Holcomb signed House Enrolled Act 1068 into law, creating a framework for justice stakeholders to convene regular meetings and conduct reviews of systemic practices in their communities.

The law also provides a direct link between the state and local JRACs, Goff said, allowing the state group to be more responsive to the needs of individual communities.

During the daylong summit, Goff led panel discussions regarding the use of local JRACs to improve community responses to mental health through evidence-based best practices in behavioral health treatment and community-based sentencing alternatives.

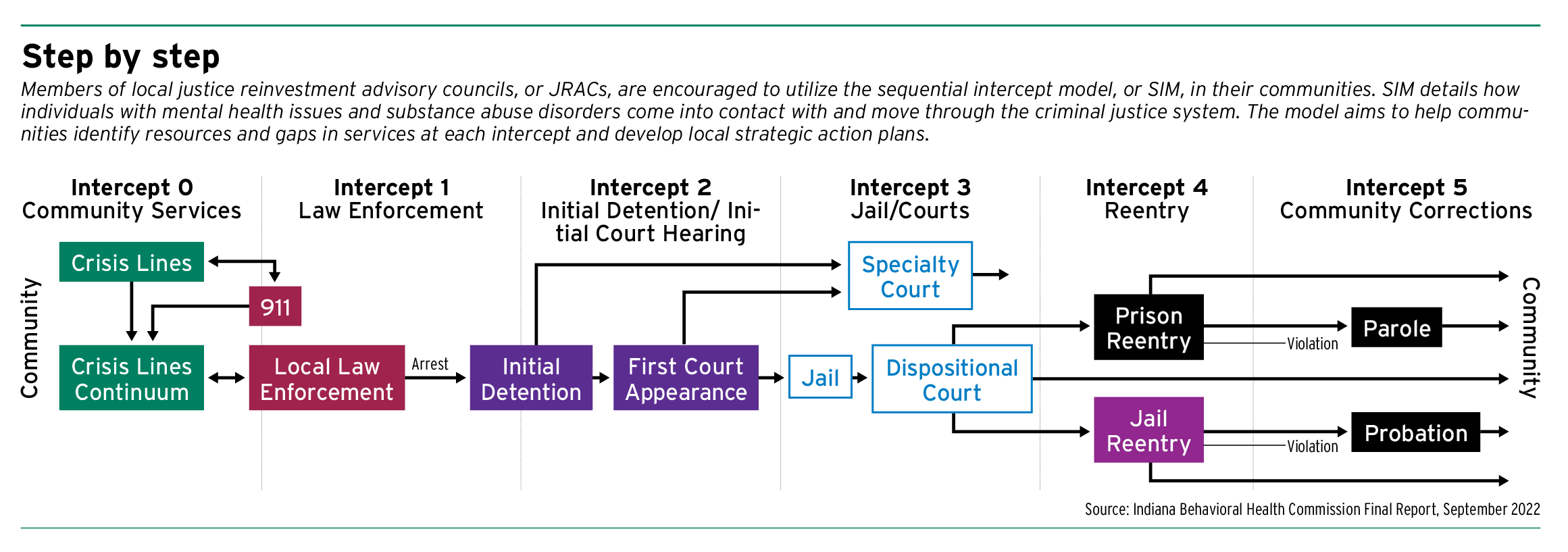

Among those best practices, he said, is the sequential intercept model, intended to take a closer look at local mental health delivery systems.

“Starting at intercept zero, before law enforcement is ever involved, what do you have if somebody needs services, short of getting arrested? What could we do better? What resources would we like to have in our community, but don’t?” Goff said. “That information then can be shared through an annual report that the local JRAC submits to state JRAC, and members of state JRAC then can have a meaningful conversation and, if appropriate, work with members who are also in the General Assembly to develop legislative initiatives that would actually be responsive to the needs of our community in this area of mental health.”

Republican legislators including Sen. Mike Crider, Sen. Jack Sandlin and Rep. Greg Steuerwald said mental health funding would be a priority during the Indiana Legislature’s upcoming budget session.

Taking it back home

One benefit of using local JRACs, Goff said, is becoming part of a statewide professional organization made up of dozens of stakeholders, ranging from law enforcement and judicial officers to behavioral experts and medical professionals.

“That’s really important, because if you’re out in the field and you are presented with a crisis, you’ve never run across this before, you need to make a good decision,” Goff said. “You need to figure out what best practices would dictate, and you could call on your professional organization to provide you some assistance in that regard.

“It allows all of the heads of the professional organizations to really kind of talk amongst themselves about, where do our best practices intersect and overlap?”

For Huntington Superior Judge Jennifer Newton, taking advantage of that overlap was a big takeaway from the summit. Newton and 11 other stakeholders from her community attended the event to try and find solutions to the revolving door of defendants struggling with mental and behavioral health.

Newton said she often sees defendants with mental health issues that are accompanied by a substance abuse disorder. But the likelihood of getting those individuals the help they need can be small, she said.

“I have a handful of defendants who need competency evaluations, and having the psychologists in the area has been very difficult to get,” the judge said. “What happens is a lot of these people are sitting in jail, which they shouldn’t be, but they are not getting the services they need.”

Newton said she hopes to take advantage of grant funding in her community and partner with the local police to utilize their newly funded crisis intervention team.

“If we bring the right people to JRAC — and I think we are — by doing more collaborative things like the crisis intervention training, we will have to come up with other ways like that to try to deal with some of these issues,” she said.

Down in Floyd County, Judge Carrie Stiller said the need for resources for people with mental health needs is “dire.” The county doesn’t have its own inpatient mental health facility, forcing it to share with surrounding counties. But beds are scarce and take months to come by, while those in need remain behind bars.

“That’s problematic for lots of reasons,” Stiller said.

Overall, Stiller said the summit was fruitful for the nine local JRAC stakeholders that attended from her county. They’ve started mapping out how to fill the gaps in their community.

“We all came away from it feeling that we had a lot of information we could apply. We already have the framework with the stakeholders working together, communicating, etc.,” she said. “The whole concept of JRAC was to identify weaknesses that you have and try to figure out solutions to restore whatever is needed.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.