Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowAs Allen County attorneys tuck their laptops into their briefcases, climb into their cars and accelerate across county lines to represent clients in neighboring communities, they are continuing the tradition of circuit riding that dates from the days when Fort Wayne was just a few hundred settlers who made a living trading furs with the Indians.

Judges and attorneys riding the circuit started arriving in Fort Wayne in 1824 after the Indiana Legislature had placed the new Allen County in the Third Circuit. The traveling legal professionals journeyed up the Quaker Trail on horseback, sometimes camping outdoors and other times lodging at roadhouses where they had to share a bed with strangers.

Over time, the circuit riders gave way to attorneys who lived in Fort Wayne and ran their law offices from their log cabin homes. Courthouses were built, law libraries were stocked, docket books were filled with handwritten entries, and eventually the lawyers were required to graduate from law school and pass the bar exam before they could practice.

Allen County Solo practitioner Donald Doxsee often wondered how the legal profession in his community flourished and changed into what it is today. Sitting in the county’s 107-year-old courthouse, he would ask himself, “How did we get here?”

Doxsee was then inspired to start researching and preserving the stories of the attorneys who came before. For the last three years, he spent many afternoons in the public library, digging through old court books and newspapers. He talked to attorneys and judges, sometimes putting them together around a table and trading memories. He made notes and photocopies and, in the evenings, he would settle in front of his computer and write.

The fruit of his labor has just been published as a book with all proceeds benefiting the Allen County Bar Foundation. Titled “A History of the Allen County Bar and Courts 1824-2019: A Light in the Forest,” the slim volume traces the legal profession from the founding of Allen County to the present day, highlighting attorneys, judges, sensational trials, legal procedures and even the demise of spittoons in the courtrooms.

Stories are the heart of the book.

“Mainly we wanted to preserve some of the old stories of the bar,” Doxsee said. “They’re interesting, and they tell us a little bit about how people lived and how we handled things in that era.”

Scandals and contributions

Retired Allen Superior Judge Stanley Levine credits Doxsee’s book with providing a counter to the grousing and badmouthing about attorneys he had heard throughout his career.

The history of Allen County is intertwined with the growth of the local legal profession. Reading between the lines of the book, Levine said, the story is clear that attorneys not only built the practice of law but also the wider community.

Certainly, the work of building was not always glamorous. Doxsee’s book includes vignettes of courtroom brawls, jailbreaks and the discovery in the 1980s that some attorneys were coercing victims of domestic violence into having sex in exchange for reduced legal fees.

As a young attorney, Doxsee spent some of his time representing clients in city court, a less formal judicial venue that dealt with petty crimes, traffic offenses, public intoxication and prostitution.

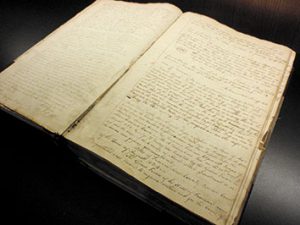

Fort Wayne attorney Donald Doxsee’s history of the legal profession in Allen County.

The court was established in 1901, and Doxsee remembered the attorneys hamming it up more than was allowed in the superior and circuit courts. For defendants who threw themselves on the mercy of the court, sometimes the judge would enter a “judgment withheld” or “continued indefinitely,” which would effectively close the matter without a fine or jail time.

His book notes the city court attracted a cast of regular observers. They clustered in the courtroom, watched the proceedings and offered their critiques of the attorneys. One regular, Sam Noolan, attended court so often, according to Doxsee’s book, the court made him an unofficial bailiff and gave him a desk near the judge’s bench.

The legal profession grew and, along the way, contributed greatly to Fort Wayne’s prosperity. Attorneys fought for the establishment of free public schools, helped a widow get restitution from B & O Railroad for the death of her husband, and worked to formalize the courts and establish problem-solving courts.

“I want the readers to understand the importance of lawyers in getting us where we are,” Doxsee said. “It wasn’t easy. Lawyers kept the rule of law and society protected and organized.”

Northern Indiana District Court Judge William Lee started practicing in 1962 in Fort Wayne. He remembered the practice being less polished and attorneys not as efficient or possessing the specialized knowledge they have today.

In fact, as a young man, Lee was discouraged from becoming a lawyer. He was told being an attorney was not a good occupation, but with college scholarships to ease the financial burden, he switched his studies from engineering to law.

Lee has been happy with his career choice, and he is glad Doxsee has collected the stories that tell of a lawyer’s everyday work through centuries.

“It’s one of the more interesting ways to make a living there is,” Lee said. “I enjoy it a lot, which is the reason why I’m still doing it.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.