Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowFor Nicole Kearney, a glass of wine can be an introduction to new friends and a way to deepen bonds with loved ones.

People with a glass of merlot or chardonnay will start by sharing their stories of which wines they have tried before the conversation progresses to other topics like favorite foods and restaurants, she explained. Before long, even total strangers will be exchanging phone numbers and social media profiles so the rapport can continue after the last bottle is empty.

“That’s what wine does; it brings you together, it connects communities,” Kearney said. “… It’s the bridge to start talking about other things.”

Kearney turned her love of the grape into Sip & Share Wines. Based in Indianapolis, the boutique winery produces about 2,000 cases of vegan wine annually. A handful of employees craft the wines while the sales team, sprinkled in different states, markets the products.

Since the business was founded in 2016, Kearney has regularly consulted with a pair of attorneys. She relies on one to provide legal advice about contracts, leases and employee agreements and the other to protect Sip & Share’s intellectual property.

Just as she does when sharing a glass of wine, Kearney has fostered tight relationships with both lawyers. Key to keeping the relationships functioning is confidentiality.

Sip & Share’s legal needs range from help with the winery’s short- and long-term plans to trademarks. Kearney said she believes having any of that become public knowledge would enable her competitors to spoil the business’s future.

“It would allow other people to know exactly what we’re doing, our growth strategy, and they could go ahead and either not copy it or, if they had more resources, kind of intercede and cut us off at the neck,” Kearney said. “So, for our business, it could be very catastrophic.”

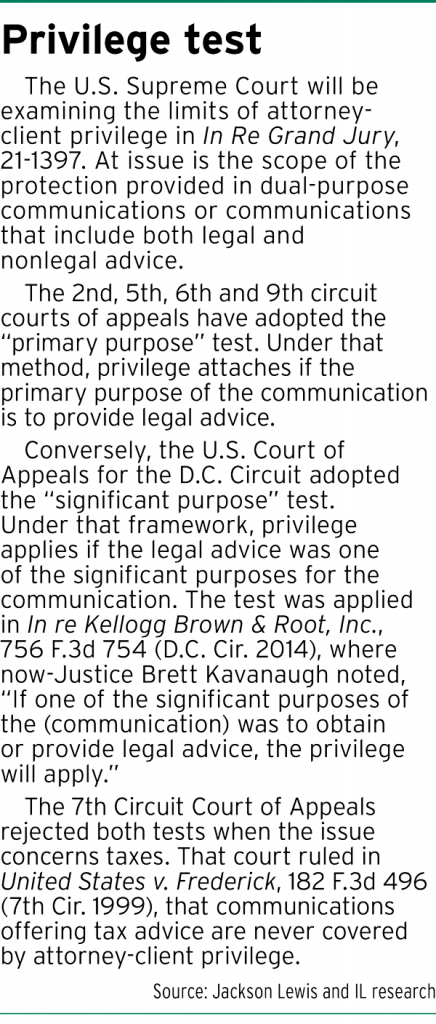

The attorney-client privilege that gives Kearney and other business owners as well as individuals the confidence to speak freely with their lawyers is going to be reviewed by the U.S. Supreme Court on Jan. 9. For the first time in more than 40 years, according to the Association of Corporate Counsel, the nine justices are set to consider what test courts should use when trying to determine if a document or conversation between a lawyer and client is private.

In the case, In Re Grand Jury, 21-1397, the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals employed a narrower test in deciding which papers the petitioner should have to turn over to the government.

Daniel Pulliam, partner at Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath in Indianapolis, is familiar with disputes over privilege. Because privilege does not blanket all communications between clients and lawyers, he said he sees the case as potentially being beneficial.

“What’s really interesting about it is you’ve got an opportunity for the U.S. Supreme Court to provide some good guidance, if not clear rules, about what is or is not privileged and the rules that courts should go about looking at and using in determining whether a party has validly asserted a privilege for purposes of withholding information that would otherwise be discoverable,” Pulliam said.

Dual-purpose communications

The petitioner in the case is a law firm that prepares tax forms and offers tax advice for clients, according to the cert petition and respondent’s brief filed with the Supreme Court. One client, who is under a criminal investigation by a federal grand jury, asked the law firm for legal advice about the tax consequences for an anticipated expatriation and to prepare income tax returns along with other forms to comply with the expatriation tax requirements.

As part of the investigation, the petitioner and two of its employees were subpoenaed for the materials related to the client’s expatriation and tax returns. The petitioner claimed to have produced more than 1,700 records exceeding 20,000 pages but withheld others, saying they were covered by attorney-client privilege.

At the 9th Circuit, the panel ruled that in dual-purpose communications — those that involve both legal and nonlegal matters — privilege extends only to the documents and conversations where the “primary purpose” was legal advice.

The opinion is at odds with the “significant purpose” test. That method holds that a dual-purpose communication is privileged if one of the reasons for the interaction with the attorney was for legal help.

Kevin Koons, partner at Kroger Gardis & Regas in Indianapolis, said he sees the “primary purpose” test as creating even more difficulty in trying to determine how far privilege extends in those instances when the legal advice bleeds into business advice. Conversely, the “significant purpose” provides clients with a better understanding of privilege because often, they contact their lawyers without realizing they are asking for more than legal assistance.

“I think as long as one of the purposes is to seek legal advice, that’s going to further the purpose of the attorney-client privilege in general, which is we want clients to be forthcoming with their lawyers,” Koons said. “We want them to feel like they can go to their lawyers, talk to them, seek advice without fear that someone’s going to pry into that.”

Expect to be protected

Pulliam pointed out another gray area can appear when the intent of the communication is for “facilitating legal advice.” The lawyer may ask the client for the facts of the situation in order to then formulate a response about the legal considerations and consequences.

Pulliam pointed out another gray area can appear when the intent of the communication is for “facilitating legal advice.” The lawyer may ask the client for the facts of the situation in order to then formulate a response about the legal considerations and consequences.

A way to clarify that the memo or conversation is confidential would be to identify at the outset that the purpose of the interaction is to give legal advice. But attorneys and clients usually do not always make such declarations when they speak or trade emails.

“People don’t talk that way, people don’t write that way,” Pulliam said. “People tend to be more informal about it. So it’s not always obvious that the communication is for the purpose of giving legal advice.”

Fallout from the Supreme Court’s decision could possibly give some clients pause when dealing with their attorneys, Koons said. They could try to figure out where privilege ends themselves.

“All you can do as a lawyer is explain to them what the test is,” Koons said. “But now, you’re relying on a person who’s not legally trained to sort of, in their own mind, make the decision about, ‘What do I share with my lawyer and not share with my lawyer?’ without having the legal basis to help know where that line is.”

The Supreme Court case shocked Kearney, she said, because she had thought everything she said to her legal counsel was confidential. Echoing attorneys, she said privilege is crucial to trusting the lawyer and having confidence in the legal advice.

“When a client goes in to speak to their attorney, privilege is an underlying right that everyone should have because we are speaking about not only our present but our future of whatever it is our craft that we’re working on,” Kearney said. “We expect to be able to be protected so that we can make the best decision for our business, and our counsel can help guide us in that.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.