Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe bar exam Indiana administered at the end of February is headed for the pile of historic has-beens as the state prepares to switch to another version and the National Conference of Bar Examiners starts the process to overhaul the entire test.

In November 2020, the Indiana Supreme Court ordered the state to adopt the Uniform Bar Exam starting with the July 2021 test, which will allow applicants who pass the ability to apply for law licenses in multiple states. The switch to the UBE means the Indiana essay portion of the exam, which tested on Indiana law with questions crafted by the Indiana lawyers, will be replaced by the Multistate Essay Examination that is formulated by the NCBE and offered across the country.

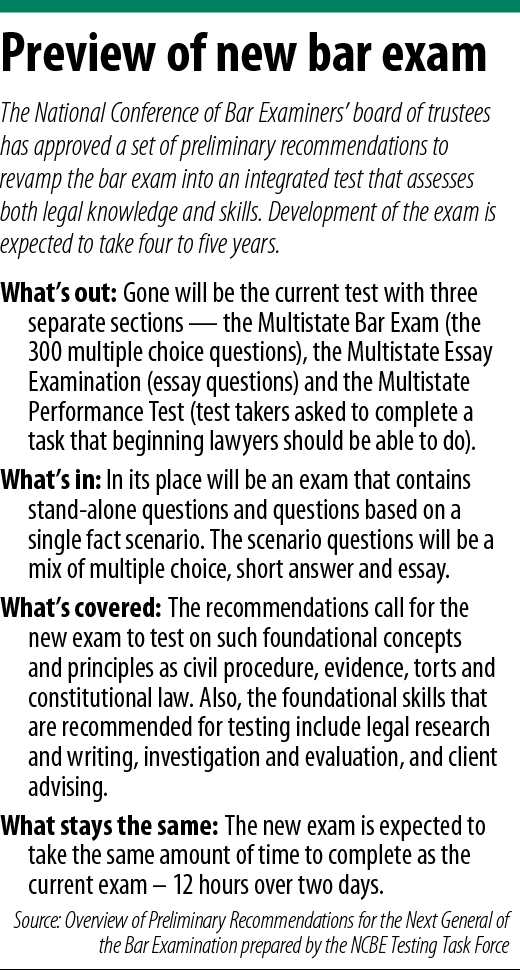

However, the MEE component along with the other sections, the Multistate Performance Test and the Multistate Bar Exam — all developed by the NCBE — are slated to be replaced by what the National Conference is calling “the next generation of the bar examination.”

Reaction is mixed over what the revamped exam will include.

Indiana attorney Leah Seigel, who served on the Study Commission on the Future of the Indiana Bar Exam that recommended the Hoosier State adopt the UBE, observed no format is perfect, but requiring lawyers to pass a licensing test is beneficial.

“I do think it makes us better lawyers in that you do have to take some time to prepare for it,” Seigel said of the bar exam. “I think there is some value because you just can’t take every practice area course in law school. So it is a good way to sort of force you to get sort of a crash course into the areas you’ve not been exposed to.”

The NCBE Testing Task Force undertook a three-year comprehensive review of the licensing test and concluded the bar exam should be a more integrated assessment of legal knowledge and practical skills.

Instead of the exam being sectionalized with essay questions being separate from the multiple-choice questions, the task force called for the test to include sections that would present real-world scenarios then ask a series of questions in a variety of formats such as short answer, essay and multiple choice.

According to the preliminary recommendations from the task force, the decisions about reforms were founded on the principle that the purpose of the bar exam is to ensure newly licensed lawyers have minimum competency. Also among the prevailing views from stakeholders was that portability of the UBE scores be maintained.

The NCBE expects the new bar exam will take four to five years to develop.

Amit Schlesinger, executive director of legal programs at Kaplan, described the recommendations as the biggest changes to the bar exam since the MBE, the multiple-choice section, was introduced in 1972.

“Overall, we are supportive of the NCBE’s changes to the exam which aim to better prepare graduated students as they venture into the legal profession,” Schlesinger said. “It seems that the new exam will test law school graduates on the skills needed to be successful practicing attorneys, based on the potential scenarios they’ll face in the workplace. That means making the exam a lot less theoretical and a lot more practical than it is now.”

Practical experience needed

Conversely, Joshua Lenon, lawyer in residence at the legal technology company Clio, said the new bar exam does not go far enough. Neither the existing exam nor the proposed exam will likely measure competency to the degree required under the Rules of Professional Conduct.

“We’re just continuing to throw a test up and act like it is the ultimate measure of lawyer competency,” Lenon said. “Instead, it is measuring how good you are at taking tests.”

Lenon advocates for bar applicants to not only be required to pass a licensing test but also to receive hands-on training. Law schools should ensure all students spend time working in the legal clinics or participating in an externship. He said the experiential learning could be moved to the summer months, since only a small portion of law students secure summer associate positions, or incorporated into the third year, when students are left pretty much on their own.

As an example, Lenon pointed to New York, which mandates that all law students complete 50 hours of pro bono service before sitting for the state’s bar exam.

“We have precedent in terms of regulating the admission of lawyers that we can include some type of community or experiential learning component,” he said, pointing to the New York program.

Seigel agreed about the need for practical skills. She maintained that law schools are teaching the knowledge of the law along with the ability to analyze and apply the law.

“I think the thing about being a lawyer is that you’re really always learning,” she said. “So I’m not sure there’s a magic point where you’ve gotten enough practical experience that you can move on to whatever is next.”

Schlesinger anticipates the changes coming to the bar exam could have a “profound effect on legal education.” But Lenon sees an advantage to instituting a more accessible limited licensing program for law school graduates to give them practical experience.

“We should not have to rely on this all or nothing pass-the-bar-exam (approach) to really bring these law students into the legal community in a very efficient manner,” Lenon said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.