Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEvery week, Chase Haller sees the remnants of the foreclosure crisis sweep across his desk.

The housing attorney at the Neighborhood Christian Legal Clinic in Indianapolis routinely counsels and advises clients who were lured by the prospect of homeownership but all too often come to his office in tears.

These are people who do not have the income or credit history to get a traditional mortgage, so they turned to seller-financed alternatives such as land contracts, lease option contracts or rent-to-buy contracts to try to get a home of their own. However, the houses they took over typically had been vacant or abandoned, suffered from vandalism and infestation, and needed expensive repairs. The payments plus renovation costs, and sometimes newly discovered liens or overdue tax bills from previous years, have thrown families into such financial distress that they lost everything.

“I’ve had more people weeping in this office over these types of things going wrong,” Haller said.

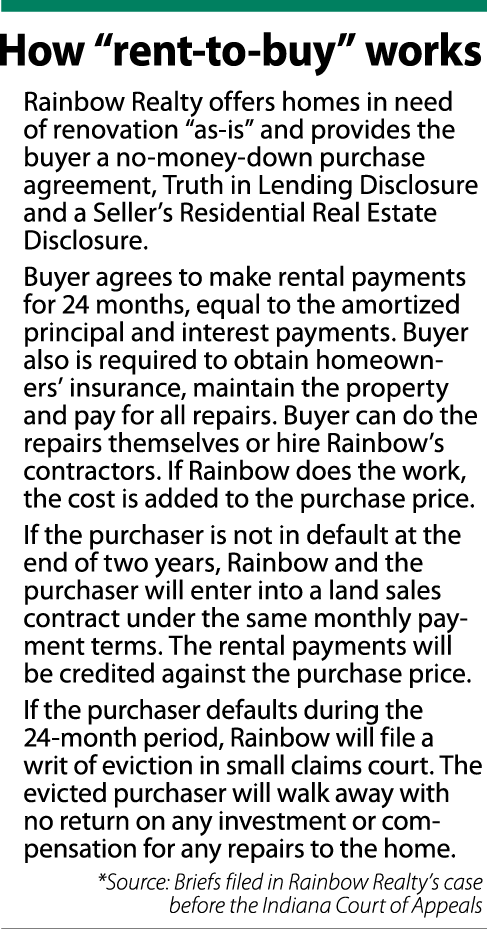

In late August, the problem moved into the Indiana Court of Appeals. The case, Rainbow Realty Group, Inc. et al. v. Katrina Carter and Quentin Lintner, 49A02-1707-CC-01473, involves a rent-to-buy contract and poses the question of whether Carter and Lintner are renters or buyers. Oral arguments lasted an hour and no ruling had been issued as of IL deadline.

Neighborhood Christian Legal Clinic attorney Chase Haller has seen families ensnared in seller-financed deals since he started in 2012. (IL Photo/Marilyn Odendahl)

Neighborhood Christian Legal Clinic attorney Chase Haller has seen families ensnared in seller-financed deals since he started in 2012. (IL Photo/Marilyn Odendahl)This is at least the third pending suit involving Rainbow Realty and its rent-to-buy program. The Indiana Attorney General filed a complaint in Marion Superior Court in January 2013, and the Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana filed a class action in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana in May 2017.

Indiana Legal Services began representing Carter and Lintner after their 2015 eviction. A Marion Superior judge granted partial summary judgment to Carter and Lintner after finding Rainbow Realty breached the warranty of habitability and made false or deceptive statements. Carter and Lintner were awarded a total of $7,000 in compensatory damages, punitive damages and attorney’s fees.

Rainbow appealed, arguing the trial court wrongly concluded the rent-to-buy agreement is governed by Indiana residential landlord-tenant statutes.

At the Court of Appeals, amicus briefs in favor of Carter and Lintner were filed by the Economic Justice Project at the Notre Dame Clinical Law Center and the National Consumer Law Center, the Neighborhood Christian Legal Center and the Indiana Attorney General.

Judith Fox, supervising attorney at the Notre Dame Clinical Law Center, asserted this case will have far-reaching ramifications. She wrote in the Center’s brief that the protections provided by Indiana Law to prevent companies from renting uninhabitable properties will be eliminated if the court finds for Rainbow.

“A ruling in Rainbow Realty’s favor will open the floodgates for other abusive sellers to enter Indiana markets,” Fox wrote.

Missing locks, broken windows

As Fox explained in the Notre Dame brief, the foreclosure crisis that began in 2008 left countless abandoned and dilapidated homes across the country, particularly in the Midwest. Investors scooped up thousands and are re-selling them through seller-financed methods.

But prospective buyers are getting trapped in homes they can neither live in safely nor afford to repair. Often the property companies evict the residents and take possession of the house without having to reimburse the former occupant for any improvements, then market the dwelling to the next prospective buyer. Fox claimed the landlords are laughing all the way to the bank.

In court filings, Rainbow’s president James Hotka said his goal in operating Rainbow was to offer affordable low-cost housing to people who wanted to become homeowners but did not have enough income to make a down payment.

He started his Indianapolis-based company in 1974, buying and selling vacant, abandoned and distressed homes in low-income neighborhoods. Since Rainbow launched the rent-to-buy program in 1992, Hotka asserted, hundreds of low-income families have successfully purchased and renovated low-cost homes.

Hotka declined to answer questions. His attorney, Karl Mulvaney, partner at Bingham Greenebaum Doll LLP, also declined to answer questions but he did say, “Mr. Hotka believes he is in compliance with state and federal laws and he is providing a valuable service for homeownership his clients wouldn’t otherwise have.”

Carter and Lintner entered into a rent-to-buy contract with Rainbow for a house on North Oakland Avenue on Indianapolis’ eastside. When the couple took possession of the residence in May 2013, doors were missing, some electrical wiring was gone, the windows were all broken, and there was no functioning sink, toilet, shower or running water.

The home had been vacant for almost three years. Rainbow’s rating system indicated the property was “absolutely not livable” and would need an estimated $5,000 in repairs to make it habitable.

Under the terms of the contract, Carter and Lintner would pay $549 per month for 30 years. Rainbow listed the purchase price of the home as $37,546 but, as Indiana Legal Services noted in its brief, at the end of the 30-year period with the interest rate of 16.3 percent, the couple would have paid nearly $185,000 for the home.

Also, per the contract, the first 24 payments Carter and Lintner made would be considered rent. If the couple made at least 24 rental payments, the parties would then execute a separate “conditional (land) sales contract” for the remaining 28 years.

Before the Court of Appeals, ILS contended Rainbow was seeking to have it “both ways.” The company treated Carter and Lintner not only like owners in holding them responsible for all renovations and maintenance of the property, but also like renters in that if they failed to make any payments during the first two years, they would be evicted.

ILS charged Rainbow’s rent-to-buy agreement is governed by Indiana’s landlord tenant laws and by the Marion County health and housing code. The contract is invalid as a lease because the company did not provide Carter and Lintner with a safe, clean and habitable home. Moreover, it is invalid as a purchase agreement because it allows for forfeiture during the first two years regardless of the investments the couple made to the property.

Rainbow pushed back, arguing the landlord-tenant laws do not apply because Carter and Lintner were purchasing the property. The initial two years of payments were not lease payments. Rather, the first 24 monthly payments were in lieu of a down payment and were credited against the purchase price.

ILS staff attorney Cheryl Koch-Martinez declined to comment on the specifics of this lawsuit. Still, she noted, that, in general, rent-to-buy contracts tend to be complex. Plus, they continue to be a barrier for low-income people looking for stable housing.

‘Need someplace to live’

‘Need someplace to live’

Rent-to-buy contracts are not illegal and can be a legitimate way to purchase property, Haller said. But some companies are crafting agreements with terms and conditions that absolve them of responsibility and trap families in situations that drain them financially and crush their dreams of homeownership.

Haller dismissed the buyer-beware notion that seller-financed agreements are the free market at work. He pointed out families in Marion County are squeezed by stagnant wages, rising housing prices and limited options for buying property.

“People are being forced into these markets dealing with these kind of contracts that have a lot of predatory features,” Haller said. “If they want to be homeowners, they have to navigate these shark-infested waters to find a reasonable opportunity to purchase a property.”

For one of Haller’s clients, the most disheartening part of her family’s ordeal with a rent-to-buy contract was having to tell the children they would not be moving into a home.

The woman, who asked not to be identified, said she and her husband wanted to get out of their apartment and into a house where they could host family barbecues and their son and daughter could play in the yard. The home they liked had a range of problems including plumbing and electrical, but the children were already planning how they were going to decorate their bedrooms.

Confusion at the contract signing along with demands for more money up front derailed the deal before the family could start unpacking. Now the family is trying to get its money back and scrambling for another place to call home.

“They’re just taking advantage of people who have no other means and no other decent place to live,” the woman said.

The Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana sees Rainbow’s tactics as targeting minority communities with exploitive contracts. In federal court, FHCCI asserted Rainbow is violating numerous federal consumer and fair-housing laws.

Amy Nelson, executive director of the Fair Housing Center, said the rise of rent-to-buy contracts is fueled by the affordable-housing crisis. People who cannot get traditional mortgages are vulnerable to having to enter seller-finance agreements that just offer choices of vacant, run-down dwellings.

She said the the business model only works for sellers if they continually evict people and find new buyers. The losers are not only the families who get tossed onto the street, but also the neighborhoods, which tend to see property values decrease further and crime increase.

And the problem likely will persist because, as Nelson said, “People need somewhere to live.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.