Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIn late June, the U.S. Supreme Court notified Tennessee that it was last call for the state’s liquor sales residency requirement — a law similar to statutes on Indiana’s books.

Seven justices found unconstitutional the Volunteer State’s mandate that anyone wanting to sell alcohol within its borders had to have lived in Tennessee for at least two years. The majority ruled the residency requirements violated the Commerce Clause, and while the 21st Amendment gives states the power to regulate assorted spirits within their borders, the live-here-to-sell-here provision tasted too much like economic protectionism.

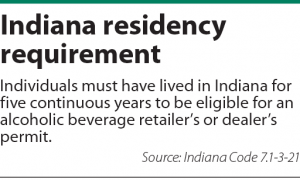

Indiana is not mentioned anywhere in the Supreme Court’s decision in Tennessee Wine & Spirits Retailers Association v. Thomas et al., 588 U.S. ___(2019), but the Hoosier state’s own prohibitions against out-of-staters selling alcohol are likely in danger.

Indiana is not mentioned anywhere in the Supreme Court’s decision in Tennessee Wine & Spirits Retailers Association v. Thomas et al., 588 U.S. ___(2019), but the Hoosier state’s own prohibitions against out-of-staters selling alcohol are likely in danger.

“The Supreme Court’s decision will ultimately lead to the undoing of Indiana’s similar residency requirements,” said Alex Intermill, partner with Bose McKinney & Evans’ hospitality and alcoholic beverage law group.

Nothing will happen automatically since the residency statute remains in place. However, Intermill explained, the law would probably not withstand a challenge in court, so the state might decide to quit enforcing the law, or the Legislature may pass an amendment removing the provision.

“I think this is a very straightforward and plain ruling from the Supreme Court,” Intermill said. “I don’t see any way around this to treat citizens from outside the state differently than those in state.”

The Indiana Alcohol & Tobacco Commission has posted a statement on its website that it is reviewing the decision to determine how or if the state’s alcohol laws are impacted. Indiana Attorney General Curtis Hill’s office did not respond to a request for comment.

Saying it was disappointed in the Supreme Court’s ruling, the Indiana Association of Beverage Retailers echoed the arguments made by the liquor store owners in Tennessee. The Volunteer State proprietors claimed that having to live where they sold made them better protectors of their communities’ health and safety against the dangers of alcohol.

“As local beverage retailers, we fully understand the risk and take responsibility for selling such a potentially dangerous, regulated product in our communities,” the IABR said in a statement. “It is worrisome that out-of-state retailers will be able to come into communities they are unfamiliar with and erode the sound public policy that our state has put in place.”

Ripple effect

Indiana has wrestled with its liquor laws in recent years. In 2017, the Indiana Alcohol Code Revision Commission was formed to review the state’s booze statutes and recommend changes. A resolution passed in the committee’s first year which led to the state allowing retail alcohol sales on Sundays.

Anderson attorney Randall Woodruff served as a member of the committee and believes protectionism flows through many of Indiana’s alcohol laws. “So many of our liquor laws don’t do anything other than protect people already in the business of selling liquor,” he said.

Residency requirements are just one example since the statutes do not include proximity in the mandate. Woodruff pointed out that a person living on the Ohio River in Evansville would be permitted to own a liquor store in Rensselaer, which is close to Lake Michigan. Then he questioned how the absentee owner living in another part of the state is able to ensure the sale of liquor from that store does not put the health and safety of the local community at risk.

Consumers, he continued, do not care whether shopkeepers are Hoosiers. If the state believes the hazards posed by liquor demand protectionist constraints, then alcohol should be banned altogether, he said.

“There should be regulations,” Woodruff said. “But the regulations shouldn’t be designed for the purpose of limiting competition and stifling access and benefiting those who are already in the business.”

One law untouched by the Tennessee Wine decision is Indiana’s prohibition against grocery and convenience stores selling cold beer. Intermill does not believe that statute is in danger, since it has withstood challenges in state and federal courts.

But, he said, the Hoosier state’s restrictions on selling liquor via the internet might now be weakened. Alcohol shipping is still a developing area of the law with no clear consensus on what can be sent in- and out-of-state.

Indeed, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals encountered the shipping question months before Tennessee Wine was argued at the Supreme Court. Lebamoff Enterprises, which operates 15 Cap ‘n Cork liquor stores in Indiana, brought the issue to the appellate panel when Illinois blocked the retailer’s attempts to sell and ship to online customers.

The 7th Circuit reversed the grant of summary judgment in Lebamoff Enterprises, Inc., et al. v. Rauner, et al. and Winer & Spirits Distributors of Illinois, 17-2495. It remanded the case to the Northern Illinois District Court for more development on the issue of when states’ regulation of alcohol as allowed under the 21st Amendment becomes economic protectionism. In its ruling, the unanimous panel noted the impending Tennessee Wine decision could impact the Lebamoff lawsuit, since the two cases are essentially about barring nonresidents from conducting business in the state.

Lebamoff’s legal team includes Robert Epstein and James Tanford, both of Epstein Cohen Seif & Porter, LLP in Indianapolis, who helped argue Granholm v. Heald, 544 U.S. 460 (2005). The pair convinced the Supreme Court to knock down the barriers states had erected that prevented out-of-state wine producers from shipping their products directly to consumers.

Epstein does not believe the potential internet sales will present formidable competition for Indiana’s brick-and-mortar alcohol retailers. Consumers will use the internet selectively, he said, just like wine connoisseurs since Granholm have logged online only to get the special brands and years that are not available at their local liquor outlet.

Saying he was “very pleased” with Tennessee Wine, Epstein sees the opinion as underscoring Granholm’s finding that the 21st Amendment does not give states the license to enact discriminatory alcohol laws.

“I couldn’t have written a better decision,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.