Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowMichael Bishop has been a commercial arbitrator since 2008.

It doesn’t really matter how big or complex any particular case is, he said — the process is essentially the same, which means he’ll see extended delays from the smallest of consumer cases all the way up to large contract cases.

“It really is the nature of the process,” Bishop said, “and not necessarily the case.”

Bishop is part of the American Arbitration Association’s commercial panel, focusing on large and complex cases. He said he’s been a mediator since 1986 and also used to be a civil litigator.

Even if delays sometimes come naturally in arbitration, Bishop can still find areas in a case where the delays are unnecessary.

He said he’s currently working on a relatively complex contract dispute within the medical device industry, and the lawyers on the case have had a number of disagreements over documents to be produced and witnesses to be available.

He said he’s currently working on a relatively complex contract dispute within the medical device industry, and the lawyers on the case have had a number of disagreements over documents to be produced and witnesses to be available.

Bishop said they’ve probably had three “extensive” phone conferences, along with motions to compel.

“That takes a lot of time,” he said.

Even in smaller cases, he said he’s asked to review disputes among lawyers about what documents should be produced.

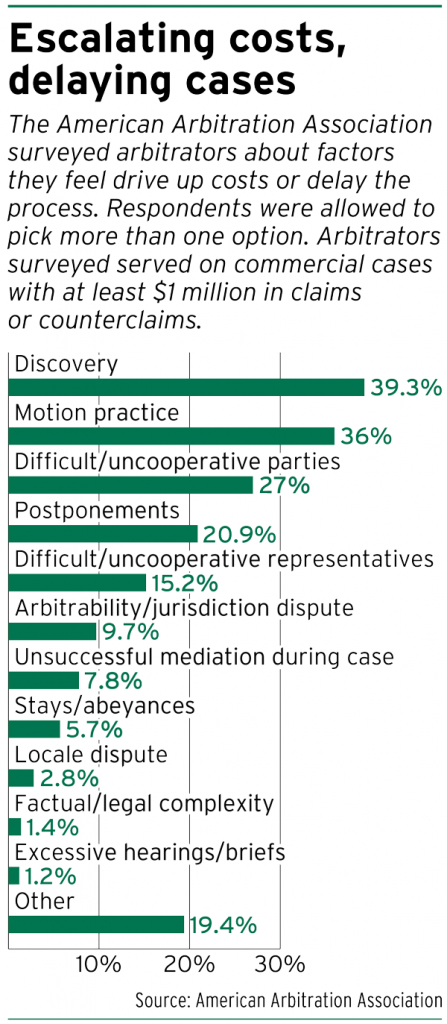

Discovery was the top factor arbitrators identified that escalates costs or delays a case, according to a survey from the American Arbitration Association.

The survey of arbitrators who worked on roughly 400 commercial cases found 39.3% of respondents said discovery contributes most to increasing costs and delays. Next was motion practice at 36%, followed by difficult or uncooperative parties at 27%.

Arbitrators surveyed served on commercial cases with at least $1 million in claims or counterclaims.

‘Move the process along’

John Krauss, who taught mediation at the Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law for about 20 years, has a trifecta of descriptors to describe what arbitration is supposed to be: “faster, quicker, simpler.”

However, Krauss said, sometimes lawyers approach arbitration as though it’s a “trial by battle” like in court.

Krauss said that could be a tactic in some instances to string out the case, or maybe there’s a power imbalance — between a pro se consumer and a large corporation, for example — that the arbitrator has to be aware of to make sure it doesn’t “get out of hand.”

“You choose arbitration because you want to simplify the process,” he said. “If you wanted to go with all the motions and all the discovery and all the depositions, go to court.”

Respondents to the American Arbitration Association survey provided a list of best practice suggestions to make arbitration more efficient.

The most common, according to the survey, is to limit discovery. Because most arbitrators don’t have mandated litigation-style discovery, they should “feel empowered to place such restrictions on discovery as they see fit to expedite the discovery phase of arbitration,” the report says.

Arbitrators also suggested agreeing upon and “strictly” enforcing a scheduling order, as well as encouraging cooperation among the parties’ counsel.

A good arbitrator won’t encourage motion practice, Krauss said.

Again, “Go to court if you want that,” he said.

“My job as an arbitrator is to move the process along,” he added.

Jerry Pitt, who’s been arbitrating cases for about 25 years and started The Mediation Center around 1995, said he sees similar issues pop up in arbitration.

A lot of times, Pitt said, lawyers come into the arbitration process with a background almost exclusively in courtroom trial work.

“They’re programmed to conduct themselves a certain way in litigation,” he said.

Pitt said most of his work in arbitration is business related, with cases such as commercial disputes, construction disputes, workplace disputes and some consumer cases.

What matters in arbitration, he said, is the facts and law.

“Theatrics don’t account for anything,” he said.

‘You’ve got to set the stage’

Krauss said arbitration is just one of the tools in the dispute resolution toolkit, and lawyers have to use their education and expertise to pick the right tool that solves problems and creates opportunities for clients.

But how does an arbitrator avoid some of the common issues that can make arbitration inefficient?

“You’ve got to set the stage at the outset that your job is to move the case along,” Krauss said.

Bishop agreed.

After he’s been selected, Bishop said he schedules a conference where everyone sits down and goes through the timeline for when discovery will be completed and how exhibits will be submitted, along with discussing the process he wants to follow.

Sometimes, Bishop said, in commercial cases there will be a contract between the parties that spells out how the process is supposed to move along.

In the absence of that, Bishop said he tries to get an understanding from the lawyers about what they need in discovery and sets limits that are tailored to the complexity of the case.

Pitt said he’s not sure how many lawyers “really understand arbitration,” but it’s important to not talk down to them.

Pitt described himsel as a mediator at heart, so he likes collaborating. That includes talking with attorneys about options available in a particular case and throwing out options for them to consider.

One option for larger cases, he said, is having witnesses prepare and sign statements, as opposed to having a lot of direct testimony. That way, everyone can read the statement, and witnesses are still available for cross-examination.

No matter what, Pitt said he wants lawyers to think creatively. If there are multiple experts, for example, he said he’s had all of them testify at the same time in a format where counsel can ask questions and the experts can ask questions of each other.

Pitt said he’s working on a case right now with a lot of money on the line. He said he’s been trying to get the parties to settle, but they can’t reach an agreement.

“What bothers me is I don’t like to see people waste money,” he said, “because it’s too hard to come by.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.