Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEven as Indianapolis Legal Aid Society has been successful at bringing in more money from grants and private donors in recent years, the nonprofit is still facing an identity crisis with people getting confused about its name as well as the services it provides.

The new chair of the nonprofit’s board of directors is launching an effort to clear the confusion and grow the contributions. John Trimble, partner at Lewis Wagner, began his two-year tenure as president in March and already has ideas for attracting more donors and expanding the nonprofit’s reach.

“I want to do all I can to help the community understand the brand of the Indianapolis Legal Aid Society,” Trimble said. “We are a law firm for the underserved.”

With about eight lawyers, the legal services agency is able to serve 5,000 to 6,000 clients per year. Trimble is proudest that people coming to the nonprofit’s offices will see a lawyer and be given representation. They will not, he said, be handed a court form and told to do it themselves.

Despite the good work, the nonprofit still has to explain what it does and correct misunderstandings over its name. The general public does not realize that ILAS represents individuals in civil actions whereas the courts will only assign a lawyer in a criminal case.

Also, its name is very close and often confused — by lawyers and nonlawyers alike — with Indiana Legal Services. The two nonprofits both help indigent clients with civil legal issues but ILS gets several million dollars annually, the bulk of its funding, from the federal government through the Legal Services Corp.

Trimble acknowledged ILAS is having to broadcast its message in age where the background noise created by the internet and social media is very loud. The biggest challenge, he said, will be to get that message to lawyers and law firms, its core group of donors, as well as the wider public without having to spend much money to raise funds.

“What we do keeps people out of the other nonprofits they may support,” Trimble said of donors.

Funding shift

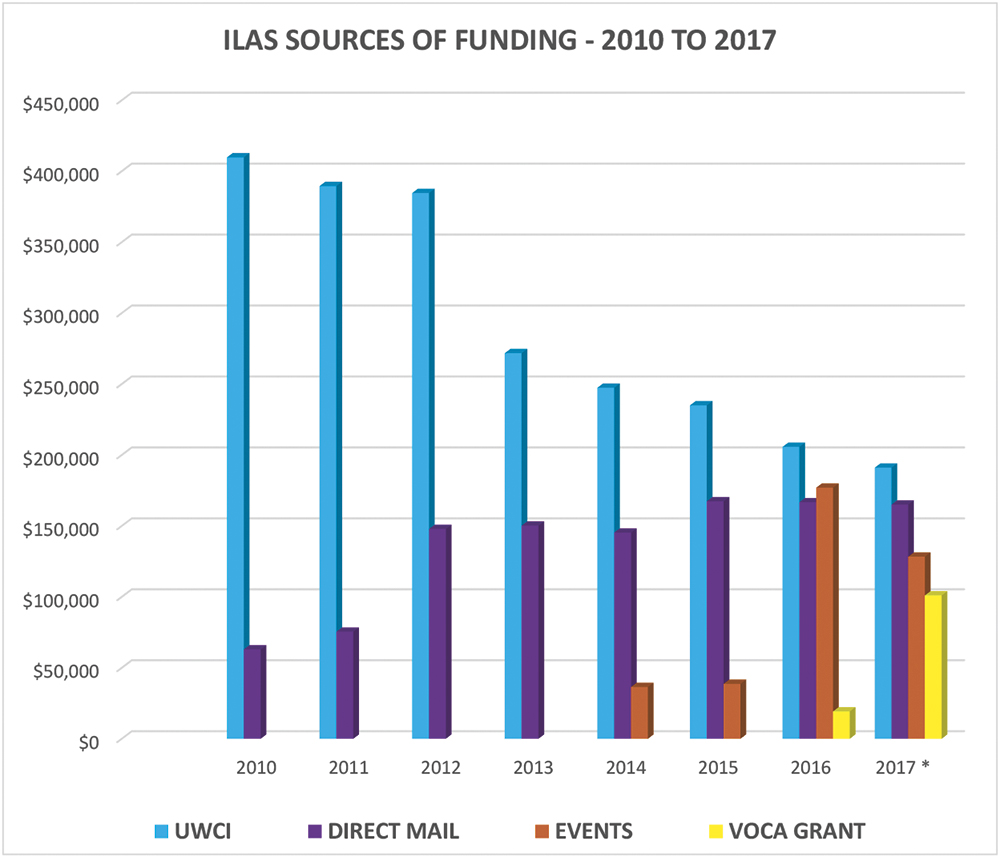

ILAS, since its founding in 1941, has received the majority of its annual funding from what is now the United Way of Central Indiana. But starting about 2013, UWCI has been changing its strategy and reducing its annual appropriation forcing the nonprofit to put more focus on its own fundraising efforts.

The United Way has slashed its funding from more than $400,000 in 2010 to less than $200,000 in 2017 to ILAS. Under the United Way’s new system, which grants money to community-based organizations, United Way has appropriated just $50,000 to ILAS as UWCI nears the end of its fiscal year on June 30.

ILAS has been successful at bolstering its coffers by securing more grants and donations from individuals.

The nonprofit has realized roughly $300,000 each year by putting renewed energy into its annual holiday campaign and by hosting a dinner in the fall that features a prominent member of the legal community being “roasted” with jokes and tall tales.

Still, John Floreancig, general counsel at ILAS, said the success has come at a cost. The nonprofit has had to shift staff to focus on fundraising and keep careful records of how the grant money is used to satisfy funders. In addition, the grants are usually limited to only addressing a specific problem, like transportation or housing, which causes Floreancig to fear that someday he may have to turn away clients that the office could normally help but cannot because of grant restrictions.

“I think we have a big task in educating the general public about what we do and how important it is,” Floreancig said. “It’s rare for a city this size to have a functioning legal aid society. Most legal aid societies are a person or two.”

Looking at the intake cards from the 1940s, Floreancig said the legal problems clients needed help with then are not much different than what they face today. Family law matters such as divorces, custody disputes and guardianships still comprise most of the work but, he said, today’s problems are more complex. Individuals will have multiple legal issues that demand more of the attorneys’ time.

Trimble conceded ILAS is treating the symptoms of society’s larger issues but, he countered, solving the legal problem will better position clients to overcome the root cause of their trouble, which often is poverty. Income inequality, educational deficiencies, and physical and emotion abuse are often the burdens clients bring when they seek legal aid.

ILAS can put people on firmer ground by doing such things as getting grandparents a guardianship so they can get medical treatment for their grandchild, helping a worker get a driver’s license to drive to their job or helping a single mom get child support so she can buy groceries or pay rent.

“We’re helping people fend for themselves,” Trimble said. “Our goal for every client who walks in the door is … economic self-sufficiency.”

Uncertain times

Bill Stanczykiewicz, the director of the Fund Raising School at the IUPUI Lilly Family School of Philanthropy, pointed out the greater flow of private dollars may actually be to the benefit of ILAS. No longer is the legal service provider overly dependent on one funder, as it was on the United Way, and thus potentially crippled if that funder goes away.

However, ILAS starts each year with a budget of zero and, like all not-for-profits, could be navigating a very different landscape caused by COVID-19. Prior to the pandemic, community-based organizations had an easier time finding money in the past five years with household incomes growing and stock market increases boosting institutional charitable funders.

Stanczykiewicz underscored the uncertainty of the times ahead, saying no one knows what donors will do in the coming months as the public health crisis continues.

A Gallup Poll conducted April 14 through 28 found that 25% of Americans plan to increase their donations in the coming year and 66% are planning to keep their donations at the same amount. Even so, Gallup pointed out that with 30% of Americans reporting direct financial harm from COVID-19, donations could shrink.

Ironically, as funding could be drying up, the need has been increasing dramatically. In the first five weeks of the COVID-19 crisis, ILAS has received an unprecedented 3,700 phone calls from people seeking help, according to Floreancig. The attorneys, working from home, have been able to assist 500.

Trimble is undeterred. He has dreams of expanding the reach of ILAS by putting a lawyer on site when a local food pantry is open so people coming for food could also see an attorney or making an attorney available through the township trustee offices. Yet turning those ideas into reality will take money.

“I foresee John (Floreancig) and I will be visiting the management committees of law firms in town, doing all we can to encourage them to encourage their lawyers to donate,” Trimble said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.