Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWithin Senate Enrolled Act 388, the words “food” and “national security” do not appear.

Yet the new law that prohibits foreign businesses from buying and owning Hoosier farmland places Indiana among the states that have enacted such statutes to ensure Americans have enough to eat.

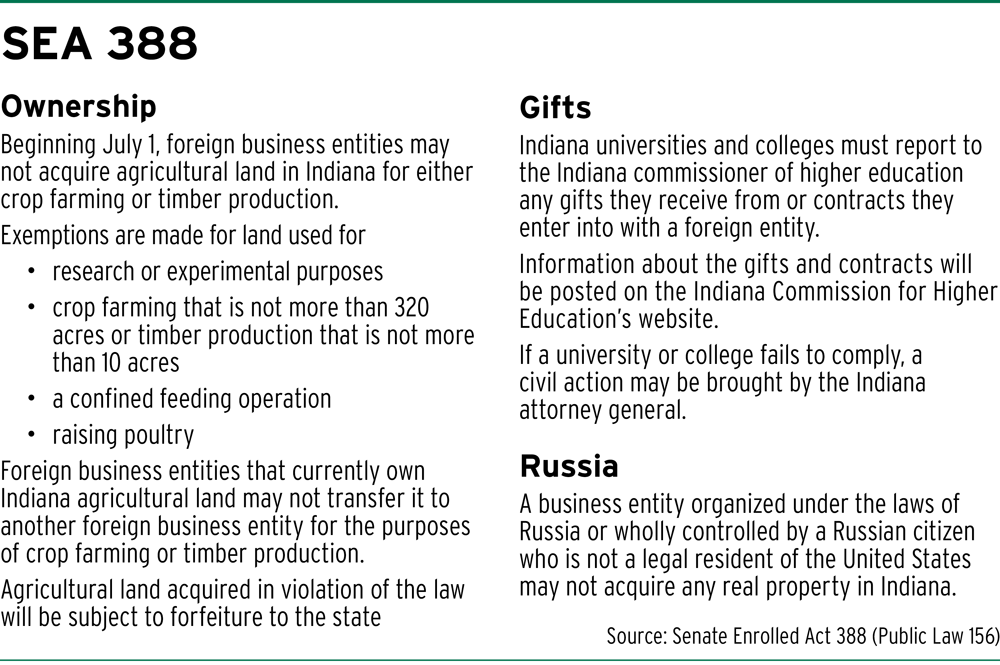

The measure, which passed with strong bipartisan support during the 2022 session of the Indiana General Assembly, prevents foreign business entities from acquiring land used for crop farming or timber production in the state. Sen. Mark Messmer, the law’s author, specifically mentioned China when discussing the issue with his Statehouse colleagues and asserted there is “a growing problem” of the Asian nation buying hundreds of thousands of acres of crop land in the United States.

The measure, which passed with strong bipartisan support during the 2022 session of the Indiana General Assembly, prevents foreign business entities from acquiring land used for crop farming or timber production in the state. Sen. Mark Messmer, the law’s author, specifically mentioned China when discussing the issue with his Statehouse colleagues and asserted there is “a growing problem” of the Asian nation buying hundreds of thousands of acres of crop land in the United States.

“It’s important that crop ground be used to supply food, food security to our country first,” Messmer, R-Jasper, told the Indiana House Committee on Agriculture and Rural Development. “With an adversary of our country buying and controlling more agricultural land every year, it will eventually become a national security issue.”

However, the law contains exemptions for livestock production, and some have questioned why foods like poultry and pork are not receiving the same protection as corn and soybeans. Also, agricultural attorneys pointed out that foreign investors can potentially get around the restriction by creating a domestic corporation and purchasing the land through that entity.

Messmer described the law as “a preventative measure” meant to address the concerns about the country maintaining the ability to feed itself.

“China might be buying it for investment — agricultural property is a great investment,” Messmer told the House committee. “But the more land of ours that they own, as a foreign Chinese business entity they could just not allow anybody to produce crops on that land if they wanted to.”

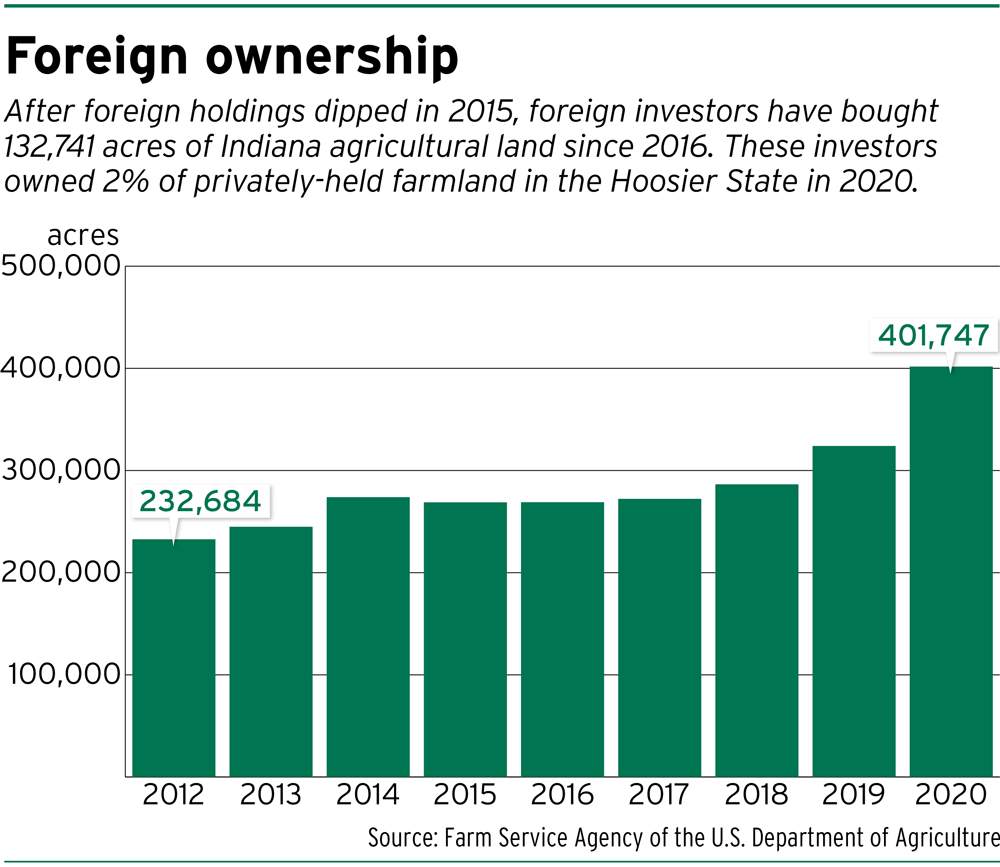

Indiana has 19.75 million acres of privately held farmland, of which 401,747, or 2%, are held by a foreign entity, according to the 2020 report on foreign investment from the U.S. Department of Agriculture Farm Service Agency. Canadian investors hold the most land at 55,578 acres in the state and, although China was singled out during the Statehouse discussions on SEA 388, that country is not among the top owners of Indiana agricultural land.

Even so, Hoosier lawmakers are not the only ones watching China. Congress is also considering legislation that would limit foreign ownership of agricultural property.

Politico reported Capitol Hill is “spooked” by the increase in foreign investors purchasing farmland and “the buyers’ potential connections to the Chinese government.”

Roger McEowen, professor of agricultural law at Washburn University School of Law in Kansas, came face-to-face with food supply fears while vacationing recently with his family in Wisconsin. The state’s license plate boasts Wisconsin is “America’s Dairyland,” but when the adults went to get milk for their 1-year-old grandson, they found only empty coolers at the local Walmart.

“A lot of the political and power struggle in the world comes down to who controls the food supply,” McEowen said. “I’m not sure a lot of people realize that.

“… You get your hands on the American food supply chain,” he continued, “you can really mess up a lot of stuff.”

Prices and purchases

Indiana farmers are not calling for curbs on foreign ownership, according to Hoosier agricultural attorneys. But farmers are concerned about the impact those foreign investors could have in bidding up the price of farmland as well as choking the food supply by shipping what they produce on American soil to their home countries.

John Schwarz, a farmer and attorney in Cass County, noted agricultural land prices have tripled in the past decade, but farmers’ profit margins have not grown proportionally. An influx of foreign dollars could add to the financial pressure by not only raising the price of land but also the property taxes, Schwarz said.

Moreover, foreign entities will not be connected to the local communities, so they might not support local retailers and service companies, Schwarz said. Also, he speculated that foreign investors may have little incentive to follow environmental regulations because draining a wetland, for example, will bring civil penalties but no criminal prosecution.

“It’s hard enough with some of these big ag groups that come in and throw their weight around, these retirement funds or other investments,” Schwarz said. “You start throwing foreigners in that could have a lot of Chinese money or whatever and now your basic farmer is just priced out of everything.”

Foreign investors held an interest in nearly 37.6 million acres of U.S. agricultural land by the end of 2020, according to the USDA Farm Service Agency. From 2009 to 2015, the holdings increased an average of 800,000 acres per year. But since 2015, the growth has accelerated to average approaching 2.2 million acres annually.

Some states in the country’s heartland have had restrictions on foreign ownership of farmland for years, McEowen said. While in the past foreign entities could easily go to another state to buy property, they are going to be getting squeezed in the market because more and more states are passing laws like SEA 388.

Some states in the country’s heartland have had restrictions on foreign ownership of farmland for years, McEowen said. While in the past foreign entities could easily go to another state to buy property, they are going to be getting squeezed in the market because more and more states are passing laws like SEA 388.

Yet McEowen acknowledged the loophole in many of these statutes enables foreign companies or governments to buy American soil. A foreign investor can use a trust, create a tiered entity or enter into a partnership with a U.S. business or investor and establish a domestic company that acts as the purchaser.

“I’ve had numerous calls over the past two to three years of attorneys contacting me on behalf of clients saying, ‘Is this business structure permissible under this particular state law?’” McEowen said. “So I know their foreign investors are asking the questions, ‘How can this transaction be structured so that we can still end up owning the land?’”

Carveouts

Kyle Mandeville, solo practitioner in Attica, said food security is more of a concern among Indiana farmers than it was 30 or 40 years ago. They believe Americans will be able to fill their plates if local farmers and U.S.-owned companies control the agricultural production.

As an example of the concern, he pointed to the 2013 acquisition of Virginia-based Smithfield Foods, America’s largest pork producer, by a Chinese company for nearly $5 billion. The fear is that the pork produced in the U.S. will be shipped to China and Americans will not have access to the meat that has “been growing in our backyard,” Mandeville said.

Some farming operations are exempted from SEA 388’s prohibitions, including poultry, confined animal feeding operations and purchases of 320 acres or less.

“Some of these carveouts, to me, are major,” Mandeville said. He explained that 320 acres could cost upwards of $4 million to $5 million, which could inflate land prices.

Also, many CAFOs are already under foreign ownership, and they will continue to have unlimited investment opportunity, he said.

“If the politicians truly want to try to protect our food safety, that’s an immediate farm-to-table issue right there,” Mandeville said. “If you want our eggs and our poultry and our hogs and our cattle to be produced and owned locally, there should have been a greater limitation there.”

Rep. Justin Moed, D-Indianapolis, likewise questioned the inclusion of exemptions in SEA 388. While he agreed that taking steps to ensure access to food is important, he pointed out the contradiction created by the carveouts.

“The intent of the bill was to make sure that folks who may not have our food security and best interest in mind are not able to buy and procure that property,” Moed said. “If the goal is to ensure food security, we’re all of the sudden carving out huge holes in that effort.”

Rep. Shane Lindauer, R-Jasper, who sponsored SEA 388 in the House, conceded he is “not a fan” of the carveouts. But he explained the German and Canadian companies that have agricultural research operations in the state were concerned their work would be hindered without the exemptions.

“My position was the bill as passed is better than what we currently have, which is nothing,” Lindauer said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.