Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThere are plenty of numbers to plainly display the lack of diversity that exists in patent law across the United States. But one of the most telling facts isn’t a number at all.

According to data collected through the American Bar Association Section of Intellectual Property Law, there are more patent attorneys and agents named Michael in the U.S. than there are racially diverse women.

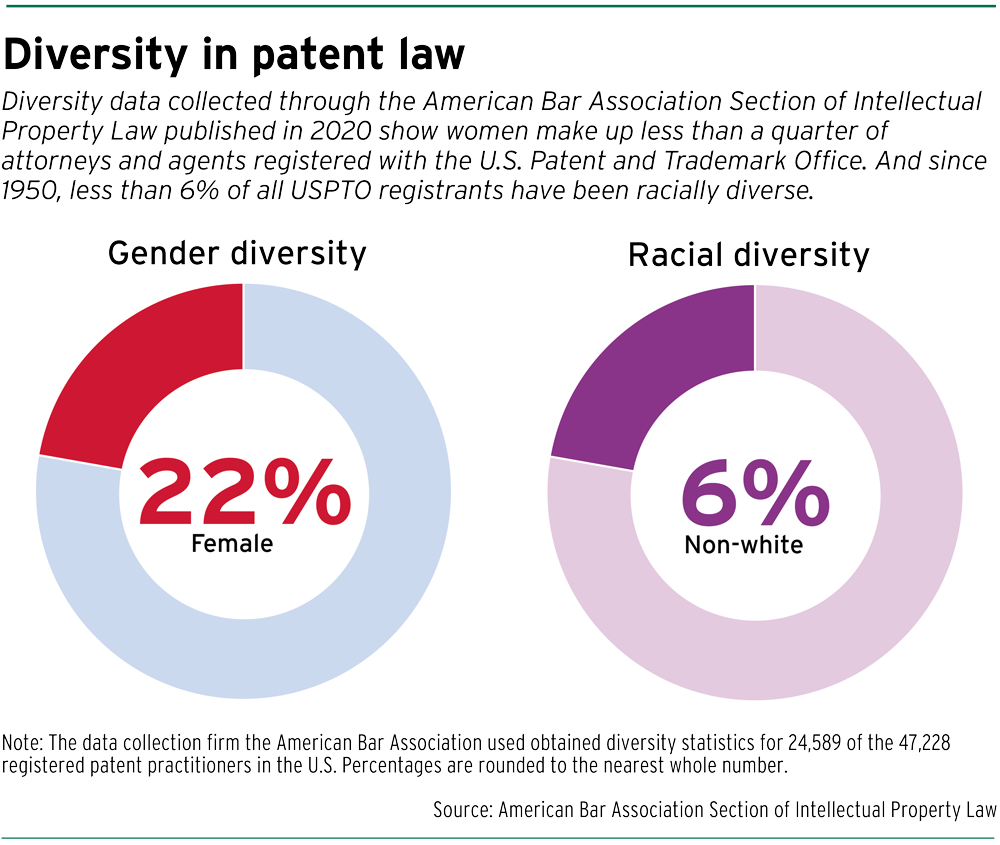

The data, published in 2020, show women make up less than a quarter of attorneys and agents registered with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office. And since 1950, less than 6% of all USPTO registrants have been racially diverse.

Holiday Banta, a partner in Ice Miller LLP’s Intellectual Property Group and registered patent attorney, said patent law’s lack of diversity is like other problems in business.

Customers and vendors may be looking for firms that are diverse — whether it’s because they feel that’s the right thing to do or because it can be helpful to have an attorney who understands their culture — and not having that can “create a friction,” Banta said.

‘STEM is huge’

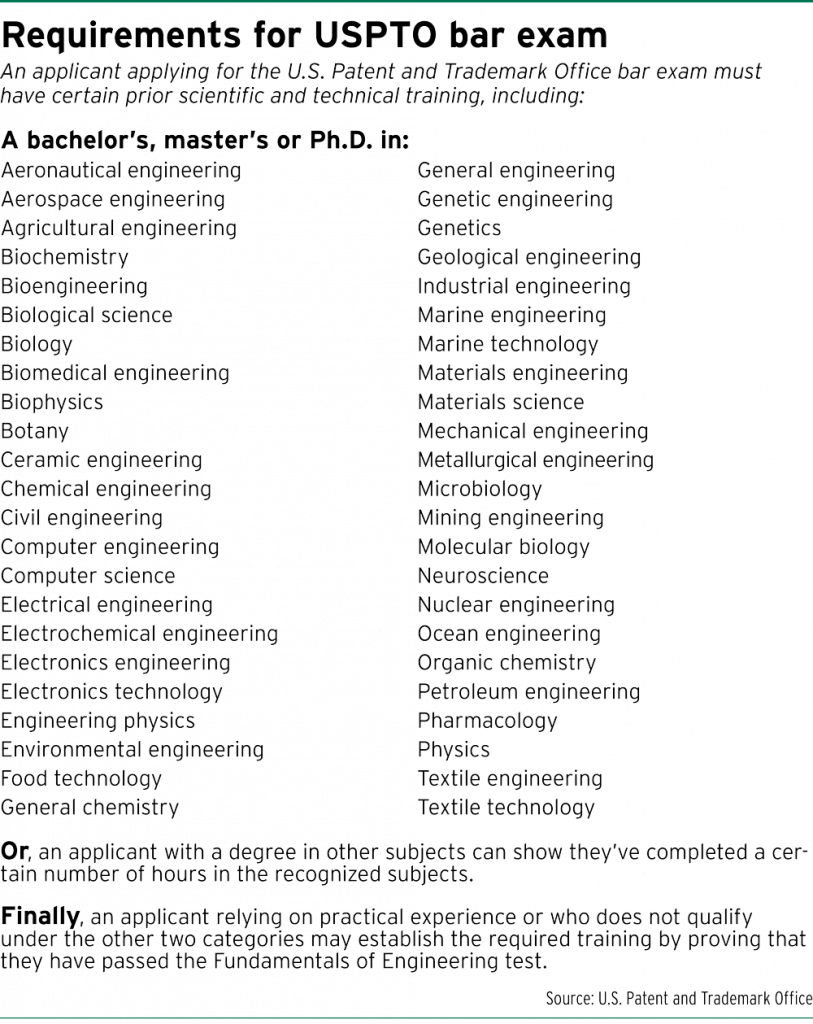

In the USPTO’s General Requirements Bulletin, there are a few options to qualify for the patent bar exam.

One option is to have a bachelor’s, master’s or Ph.D. in at least one of dozens of approved degrees, which range from biophysics and aerospace engineering to microbiology and neuroscience.

Applicants can get a degree in another subject and still qualify for the exam, as long as they can show they’ve received enough training in one of the recognized subjects — 30 semester hours in chemistry, for example.

Applicants can get a degree in another subject and still qualify for the exam, as long as they can show they’ve received enough training in one of the recognized subjects — 30 semester hours in chemistry, for example.

Finally, an applicant can rely on “practical engineering or scientific experience” by passing the Fundamentals of Engineering test.

“STEM is huge,” Banta said.

Banta, who has a degree in biology, said she didn’t even know being a patent attorney was an option for a long time.

“You have to have a very unique personality that has a science background and also wants to be a lawyer,” she said of the challenge of increasing diversity in patent law.

Katharine Wolanyk, managing director at Burford Capital, said the STEM — science, technology, engineering and math — requirements to be registered with the USPTO turn patent law diversity into something of a pipeline problem.

“It is a very, very challenging situation,” said Wolanyk, who has an engineering degree and leads Burford’s intellectual property and patent litigation finance business.

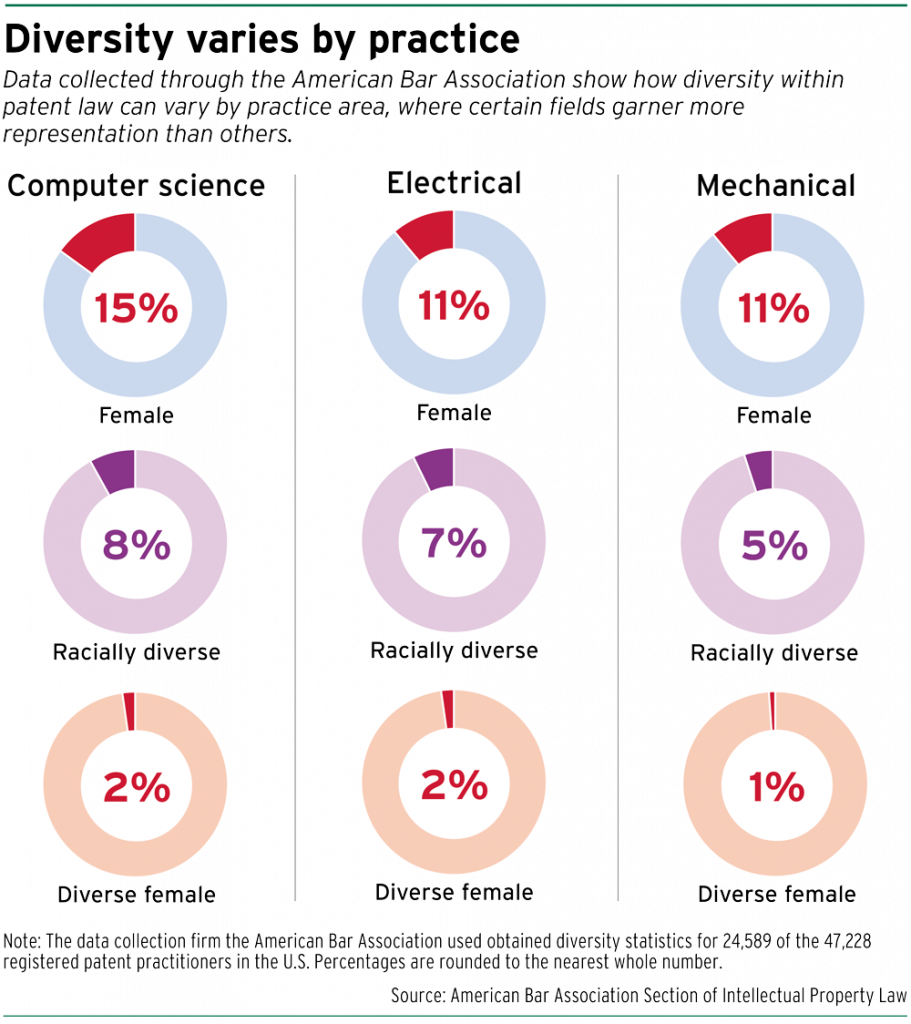

Women have made good strides in law generally, she said, but intellectual property is a narrower set of practitioners.

“It’s a societal challenge,” Wolanyk said. “Fill the pipeline with more diversity and some of these other buckets will be affected, as well.”

Part of the issue is that STEM is dealing with its own diversity struggles.

According to the National Center for Science and Engineering Statistics, only about 4.5% of engineering bachelor’s degrees went to Black or African American students in 2020, which was virtually unchanged from 2011. For women, that number was 24% in 2020, compared to 19% in 2011.

Wolanyk wrote about patent law diversity last year.

Diversifying STEM — the pipeline — is part of the solution, Wolanyk wrote, but in the meantime, intellectual property partners can take action, including through Burford’s equity program that financially backs commercial litigation and arbitration led by women.

Not a job you see on TV

Bill McKenna, a partner at Woodard Emhardt Henry Reeves & Wagner LLP, said mentorship can be a valuable tool in diversifying patent law because it’s not a profession that gets much exposure through popular media.

“IP law’s not really a job you hear about or see on TV when you’re young,” he said.

And by the time someone does learn they can make a career in law out of STEM, McKenna said it might be too late.

“There’s so many boxes you have to check along the road,” he said.

The Indianapolis firm is trying to address that issue through a scholarship program. Earlier this year, the firm awarded a $5,000 STEM scholarship to a high school senior from Purdue Polytechnic High School in Indianapolis.

The USPATENT.COM STEM Scholarship is first meant to encourage more diverse students to get a STEM degree. And although committing to attend law school isn’t a requirement to receive the award, the firm hopes that’s what students ultimately choose.

The USPATENT.COM STEM Scholarship is first meant to encourage more diverse students to get a STEM degree. And although committing to attend law school isn’t a requirement to receive the award, the firm hopes that’s what students ultimately choose.

“Hopefully those students will have the undergraduate degree they need and be aware of our job and what we do,” McKenna said.

Thinking back to when he was in law school, McKenna said that out of around 200 students, only a few would have been eligible to sit for the patent bar.

Indiana is already a state that struggles to match the demand for lawyers, and the numbers only get smallerp when considering a STEM background.

“You’re taking a narrow subset of a narrow subset,” McKenna said.

Recent USPTO changes

The USPTO, which recently celebrated issuing its 1 millionth design patent, requested public input on the possible creation of a design patent practitioner bar. The comment period closed in August.

According to a notice on the Federal Register, a design patent practitioner bar wouldn’t impact those who are already registered to practice in patent matters before the USPTO.

The USPTO also recently implemented changes to the scientific and technical criteria for admission to practice in patent matters. That included making a modification to the accreditation requirement for computer science degrees so that all bachelor’s degrees in computer science from an accredited school will be accepted.

Previously, the USPTO accepted computer science degrees accredited by the Computer Science Accreditation Commission of the Computing Sciences Accreditation Board or the Computing Accreditation Commission of the Accreditation Board for Engineering and Technology.

A notice filed by the agency in May doesn’t explicitly mention diversity, but it does say the goal is to increase access.

“Expanding the admission criteria of the patent bar,” the notice says, “would encourage broader participation and keep up with the ever-evolving technology and related teachings that qualify someone to practice before the USPTO.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.