Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowTo add further protection to juveniles’ rights when they’re interrogated by police, a new Indiana law passed this legislative session puts the onus on law enforcement to always be truthful.

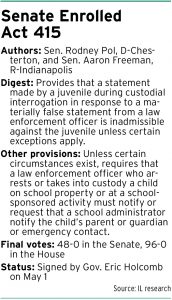

Senate Enrolled Act 415, which was signed by Gov. Eric Holcomb on May 1, provides that a statement made by a juvenile during a custodial interrogation in response to a materially false statement from a law enforcement officer is inadmissible in court, unless certain exceptions apply.

Sen. Rodney Pol Jr., D-Chesterton, authored the bill along with Sen. Aaron Freeman, R-Indianapolis.

Pol said he worked with the Indiana Public Defender Council on the legislation. Pol himself worked in public defense at the state’s Public Defender Office early in his career.

“It’s always been something that bothered me in the investigatory process,” Pol said of false statements given to juveniles during interrogation.

The bill also requires that, unless certain circumstances exist, a law enforcement officer who arrests or takes into custody a child on school property or at a school-sponsored activity must notify or request a school administrator to notify the child’s parent, guardian or emergency contact.

With the way technology has evolved, with kids frequently using their phones and posting things on social media, Pol said it’s hard to see why law enforcement would need to lie to elicit information, especially when kids often don’t know their rights.

SEA 415 drew support from a wide range of juvenile law advocates, child psychologists, the Indiana Public Defender Council and the executive director of the Center for Justice and Post-Exoneration Assistance at Purdue University Northwest.

One person who testified in favor of the bill before the Senate Committee on Corrections and Criminal Law was JauNae Hanger, president of the Children’s Policy and Law Initiative of Indiana, who said the bill would add a layer of protection to juvenile rights.

Hanger read written testimony from Ann Lagges, a psychologist at Riley Hospital for Children and a faculty member with the Indiana University School of Medicine.

According to Hanger, as part of her work for the past 16 years, Lagges has conducted competency evaluations for juveniles facing charges in the Marion County Juvenile Court. She described children and adolescents as less likely than adults to understand that an officer, who is a person in a position of authority, is permitted to engage in deception during an interrogation.

According to Hanger, as part of her work for the past 16 years, Lagges has conducted competency evaluations for juveniles facing charges in the Marion County Juvenile Court. She described children and adolescents as less likely than adults to understand that an officer, who is a person in a position of authority, is permitted to engage in deception during an interrogation.

That’s in part because most children and adolescents understand “lying” to be wrong and assume that adults, particularly those in authority positions, would “get in trouble” for engaging in deception, Lagges wrote.

“Children and adolescents are likely to draw from experiences with parents and teachers in which they are told that they will be in less trouble if they just admit to doing the thing they’re being accused of. It is not unusual for children and adolescents to admit to minor rule infractions to just end the interaction and move on,” Lagges wrote.

Speaking to Indiana Lawyer, Hanger noted children’s brain development is much different than adults. She said the power of suggestion and misleading information can lead to false confessions from juveniles.

Fabiana Alceste, an assistant professor of psychology at Butler University, testified that approximately 30% of wrongful convictions that have been overturned by DNA exonerations have involved false confessions. Of those cases, 31% of those false confessors were under the age of 18 at the time of the arrest, she said.

Further, minors are biologically susceptible to interrogative pressures until about the age of 25, Alceste added. She said the prefrontal cortex — the part of the brain associated with planning, foresight, impulse control and self-regulation — is not fully developed until then.

Alceste also told legislators that one of the most highly cited reasons minors give for giving a false confession is thinking they are going to get to go home.

Prior to SEA 415, there wasn’t any law in Indiana that addressed the issues raised in the bill, Hanger said.

“This particular legislation will contribute to fairness and due process in our legal proceedings,” she said.

Nicky Jackson, professor of criminal justice and executive director of the Center for Justice and Post-Exoneration Assistance at Purdue University Northwest told IL that she is a strong supporter of the bill and had met with Pol and Holcomb to offer input on SEA 415.

Nicky Jackson, professor of criminal justice and executive director of the Center for Justice and Post-Exoneration Assistance at Purdue University Northwest told IL that she is a strong supporter of the bill and had met with Pol and Holcomb to offer input on SEA 415.

“I think this is a great start for Indiana,” Jackson said.

Jackson has worked with many people who falsely confessed to crimes. Not all confessions are the same, she said, with some being voluntary and others “compliant confessions,” meaning someone confesses falsely after being subjected to psychological coercion.

“The bottom line is, you shouldn’t be able to lie. You and I can’t lie, so why should they (police) be able to lie?” Jackson said.

Prosecutorial support

The Indiana Prosecuting Attorneys Council was the only group to initially register any reservations about the bill before the Senate committee.

Courtney Curtis, IPAC’s assistant executive director, told committee members that there were already multiple layers of protections in place for juveniles and custodial parents in Indiana.

“We’re one of the few states that have these multiple protections,” Curtis said.

Tracy Fitz, IPAC’s juvenile resource prosecutor, said the group didn’t feel the bill was necessarily needed at first, given the protections granted under Indiana law to juveniles and adults.

Fitz cited Indiana Code § 31-32-5-4, which provides six sets of circumstances that juvenile courts must consider for juvenile interrogations and waiver of rights.

She also acknowledged that people hear horror stories about false confessions, but she stressed that every custodial interrogation has to be taped, both via audio and video, and all office interactions with juveniles must be recorded.

Fitz noted the originally introduced bill didn’t have a “good faith exception,” which was added through amendment and included in the final bill signed by Holcomb. That section provides an exception for “if a law enforcement officer or school resource officer communicates materially false information or a materially false statement with a reasonable good faith belief that the information was true at the time it was communicated to the juvenile.”

Jackson reiterated her support for the bill but said she had some misgivings about the good-faith exception, as well as other exceptions in the bill that she said she felt left room for misinterpretation.

But Fitz said once the good-faith exception was included, IPAC felt better about the bill and was no longer opposed.

“We were happy to work with them on the bill,” she said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.