Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowIndiana Southern District Court Chief Judge Tanya Walton Pratt is no stranger to breaking barriers, but a recent announcement from President Joe Biden left her inspired.

“I have long been a cheerleader for women’s achievement, especially Black women. It is difficult to navigate our careers and successes in the world,” said Pratt, who is the first Black female judge and chief judge in the Indiana federal courts’ 200-plus-year history.

Pratt has joined a chorus of elation prompted by Biden’s recent announcement that he intends to make good on his promise to appoint the first Black woman to the Supreme Court of the United States when Justice Stephen Breyer leaves the bench. She said she’s thrilled because Supreme Court decisions affect every American, and she hopes the push to diversify federal judges and the appointment of a Black woman justice will make an impact on the judiciary from top to bottom.

“If the highest court of the land looks more like the people who live in the nation, then hopefully that will trickle down into the state courts as well as all branches of the federal courts,” she said.

At both the federal and state levels, Indiana’s courts lack representation by Black women. With Biden’s pick likely coming by the end of the month, many legal professionals in the Hoosier State say they hope the president’s decision will lead to greater judicial diversity at all levels.

Federal courts

The first Black federal judge took office in 1945, according to the 2021 ABA Profile of the Legal Profession. Since then, the per-year confirmation of Black judges to the federal bench peaked in 1994, with 24 appointments.

By January 2010, 12% of all federal judges confirmed were Black, according to American Bar Association data. The numbers since have remained virtually unchanged, with the percentage dropping slightly in 2021 to 9.8% from 10.8% in 2016.

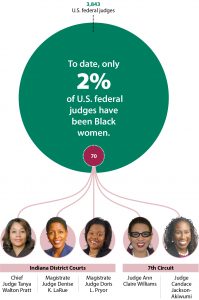

In Indiana, which is about 10% Black in terms of population, the number of Black female judges is few. To date, no Black women have sat on the state’s Northern District Court bench, while just three Black women have been appointed to the Southern District Court bench.

In Indiana, which is about 10% Black in terms of population, the number of Black female judges is few. To date, no Black women have sat on the state’s Northern District Court bench, while just three Black women have been appointed to the Southern District Court bench.

Pratt was appointed to the federal bench in 2010 and named chief judge in 2021. The late Magistrate Judge Denise K. LaRue and current Magistrate Judge Doris L. Pryor joined her in 2011 and 2018, respectively.

The 7th Circuit Court of Appeals has only ever had two Black women on the bench in its history. Retired Judge Ann Claire Williams became the first in 1999, serving until 2018, and Candace Jackson-Akiwumi was appointed by Biden in July 2021.

“It’s been a slow growth for women, Black women in particular, to get into the federal courts system,” Pratt said. “Adding a Black woman to (SCOTUS) will mean that lived experiences in all segments of the nation are a part of the conversation with these justices that deliberate.”

Carl Tobias, professor at the University of Richmond School of Law and an expert in federal judicial selection, said Biden’s nomination will be historic.

“President Biden has actually doubled the number of Black women who serve on the federal appellate courts in his first year. I think it’s important to make it a priority,” Tobias said. “There are pretty well-established reasons why it’s good to have ethnic diversity in the federal courts. They make better decisions and have different perspectives. It makes the people governed by the courts have perhaps an improved view of the courts, and more trust in the courts. And it’s important the courts reflect the society at large whose decisions affect people.”

Pratt said that in the past, the pool of potential nominees was small because there were few Black women lawyers. Today, she said more women and people of color are graduating from top law schools and receiving judicial clerkships, which often serve as pathways to the federal courts.

Regardless of race, the chief judge said she thinks the prospective candidates under Biden’s consideration are “all highly respected and extremely qualified potential nominees.”

According to The Associated Press, the president is considering “about four people” for the high court. The top three contenders are reportedly Judge J. Michelle Childs of the U.S. District Court for the District of South Carolina, Judge Ketanji Brown Jackson of the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals and California Supreme Court Justice Leondra Kruger. A handful of other Black women are also reportedly under consideration.

State court impact

In Indiana, only one Black female justice has served on the state’s highest court.

Myra Selby was appointed as both the first woman and first Black justice on the Indiana Supreme Court in 1995. She served until 1999 and was tapped by former President Barack Obama in to fill the vacancy on the 7th Circuit created by the retirement of Judge John Tinder in 2015.

However, Selby did not join the federal appeals court, as her confirmation was blocked by then-Republican Indiana Sen. Dan Coats. Selby never received a hearing before the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary and the job was given to now-SCOTUS Justice Amy Coney Barrett.

While Selby was a justice, the Indiana Supreme Court Commission on Race and Gender Fairness was created. She is still currently the chair of the commission, but she declined an interview request.

Additional efforts to help diversify the courts came in June 2021 when the Indiana Supreme Court created the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion.

There has been just one other Black justice since Selby left the bench, now-retired Justice Robert D. Rucker, and one other woman, current Chief Justice Loretta Rush.

“When I started law school a woman had never served on the United States Supreme Court,” Rush said in a statement. “I very well remember Ronald Reagan said he would appoint a woman to the highest court. And what an appointment he made with Sandra Day O’Connor who served with such distinction.”

Earlier this month, the Indiana Supreme Court announced its list of 19 applicants to fill Justice Steven David’s spot once he retires this fall. Candidates include six women, none of whom are Black, and three men of color.

According to the ABA’s 2021 Profile of the Legal Profession, 28 state supreme courts were all white, including the Indiana Supreme Court.

Meanwhile, the Court of Appeals of Indiana has never had a Black woman serve on the bench. Only three Black men and 10 women have served on the COA.

The Indiana Supreme Court doesn’t have historical information on race for its trial court judges. An Indiana Supreme Court spokeswoman said lawyers voluntarily submit gender and race/ethnicity information to the Indiana Courts Portal during annual registration. Those that responded included 20 judicial officers who currently identify as African American females.

Judge Cynthia Ayers, the first Black presiding judge for the Marion Superior Courts, said the appointment of a Black woman to SCOTUS will open doors at the federal and state levels for others.

“The addition of any of the highly-credentialed black women, currently on the candidate list for appointment to the U.S. Supreme Court, will be a great asset to the country from the standpoint, not only of their legal abilities, but also from their life experiences,” Ayers said in an email to Indiana Lawyer. “This choice will go a long way in ensuring a more equal delivery of justice and will serve as an example of the intrinsic value of diversity in judicial selection for every court in America.”

Giving a boost

As a kid in Indianapolis, attorney Katie Jackson-Lindsay remembers watching Pratt climb the legal ladder.

“From that, I knew I could be a lawyer. If (Pratt) could be a judge, I could be a lawyer,” said Jackson-Lindsay, who now serves as president of the Marion County Bar Association.

The 2021 ABA National Lawyer Population Survey estimated there are 15,802 attorneys in Indiana, but it’s unclear how many Black female attorneys there are in the state. Like the Supreme Court, the Indiana State Bar Association makes it optional for members to report their race and ethnicity.

A 2020 ABA study, “Left Out and Left Behind: The Hurdles, Hassles, and Heartaches of Achieving Long-Term Legal Careers for Women of Color,” found that 15% of all law firm associates in the country were women of color while less than 4% were partners.

Jackson-Lindsay, who is also on the Marion County Judicial Selection Committee, said there are many barriers that Black women can face in getting to the bench. She said Indiana Gov. Eric Holcomb’s 2020 decision to appoint three Black judges in Marion County, including Magistrate Judge Marshelle Broadwell, could “move mountains.”

“At the most basic level, a barrier I’ve personally faced, and my colleagues have faced, we’re often assumed as being less qualified,” Jackson-Lindsay said. “If I go into a courtroom, it’s assumed, no matter how well I’m dressed or if I’m carrying a file, I’m not an attorney. … I think there’s an inherent bias that Black women are just not attorneys. And then there’s an assumption that because we are, we got into the position we’re in because of some sort of favor or policy or filling a quota.”

Jackson-Lindsay said it’s important that judges reflect their communities, and she hopes the newest SCOTUS justice will have an impact on Indiana.

“I think (the SCOTUS choice) will solidify our belief as Black female lawyers locally that we are qualified, and this can happen for us,” she said. “The days of us being overlooked are slowly fading away. That trickles down to the future generation of little Black lawyers that aren’t even in high school yet.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.