Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowRichmond attorney David Burton still gets the occasional call from a family whose children have been exposed to lead.

The cofounder of Burton & Simkin litigated a lead case in 2007 for two families with small children and was able to reach a settlement that gave the youngsters some financial resources to help cover their medical and rehabilitative care. He subsequently wrote and posted a synopsis of the lawsuit to his firm’s website, so likely after a Google search, parents are calling him for help.

However, Burton has to explain the heartbreaking reality that a lawsuit would probably not be worth pursuing. Unless the landlord has deep pockets, the families would not be able to recover damages because most insurance policies that cover rental properties include exclusions for lead.

If more resources were available for families to pursue, Burton expects more and more lead-based personal injury cases would be filed, which, in turn, would create an incentive for landlords to remedy the problem in their properties.

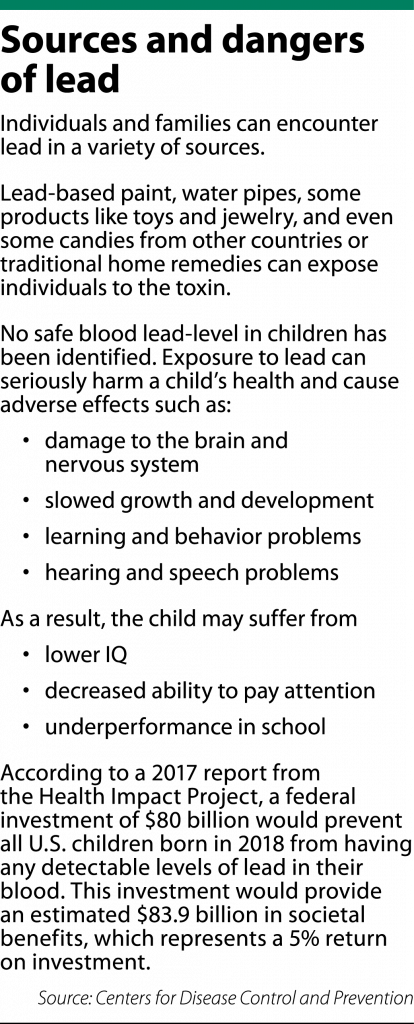

Like the mothers and fathers who call Burton, organizations and individuals around Indiana have been pushing for a solution to the lead problem. The toxin is everywhere and exposure, especially in very young children, can cause lifelong cognitive impairment.

Young Hoosiers encounter lead in the places they know well and may consider safest. They ingest it when they pop into their mouths a chip of the lead-based paint that peels from the walls in many of Indiana’s older homes, and they swallow it when they take a sip from a drinking fountain that is connected to lead pipes in their school. Also, they breathe it when the dust rises from the interior paint and even the soil outside.

In 2016, the families in the West Calumet Housing Complex in East Chicago had to uproot their lives when they were ordered to vacate the premises because of lead and arsenic. Their homes had been built on a former industrial site, and the levels of contaminants in the ground posed too dangerous a health hazard for the people to continue living there.

The events in East Chicago demonstrate that often, families are unaware they are at risk. Their children might struggle in school or wind up in prison, and they never know the real culprit was the lead in their surroundings that damaged their youngsters’ brains.

“There’s probably a generation of children around the state who have been poisoned (by lead) and don’t know it,” said Garry Holland, education chair of the Greater Indianapolis Branch of the NAACP.

Grassroots

The Indianapolis NAACP has been active in educating the community about the hazards of lead and in pressuring the Statehouse to address the lead problem. It has hosted panel discussions with assorted experts and has rallied behind legislation calling for more testing.

House Bill 1265, authored by Rep. Carolyn Jackson, D-Hammond, has gotten the most traction of the handful of lead bills that were introduced during the 2020 session of the Indiana General Assembly.

Jackson’s bill requires the drinking water in Indiana school buildings to be tested before Jan. 1, 2023, and if the level is equal to or higher than 15 parts per billion, steps have to be taken to reduce the amount of lead in the water.

The cost of testing is estimated to reach $1 million, with the bill noting that state and federal grant money is available for which schools can apply. But according to the fiscal analysis, schools would be responsible for remediating any taps and faucets found to be out of compliance, which would add interminable costs.

HB 1265 was scheduled for a second reading March 2 in the Indiana Senate.

Sen. Jean Breaux, D-Indianapolis, also introduced two bills pertaining to lead.

Senate Bill 285 required all Indiana children on Medicaid to be screened for lead poisoning. Senate Bill 286 attempted to institute some preventive measures by requiring all children to be tested for lead before being allowed to enroll in school and by prohibiting homes with a “lead hazard” from being rented to families with children 6 years old and younger.

Neither bill was given a committee hearing.

Rep. Vanessa Summers said the community advocates are doing the right thing in testifying about lead at committee hearings and giving legislators reading materials. For elected officials to take action, Summers said, they need to realize their children and grandchildren could be at risk for lead poisoning and that lead contamination is an urban as well as rural problem.

“Educate, educate, educate, and always put something in their face so they know and keep reminding them it doesn’t matter how much it is, it’s for the babies,” the Indianapolis Democrat explained.

Beyond testing

Although focused on getting a testing bill through the Legislature, the Indianapolis NAACP is also looking at what should happen after a child is found to have an elevated level of lead in his or her blood.

Holland said the organization is concentrating on ways to mitigate the damage. After a child is found to have been exposed to lead, the next step will be to do additional exams to determine what therapies and services will be needed to ensure the child does well in school and ultimately becomes a productive citizen.

The cost to the state for such programs and initiatives to help the children will be far less than having to pay for special education or incarceration, Holland said.

Kristina Box, Indiana state health commissioner, agreed: “Testing is not the end.”

The Indiana State Department of Health is turning its attention to very young children and finding out where the exposure is. Box said her agency is working to test infants and toddlers for lead, because even though Medicaid requires children at 12 and 24 months to have a blood lead level test, only 21% of Hoosier kids are getting screened.

After the testing, the focus shifts to locating and remediating the source.

After the testing, the focus shifts to locating and remediating the source.

“It’s identifying that child that has an elevated level of lead and … finding out where the child is coming in contact with it,” Box said.

Litigation

Burton knows from experience that proving personal injury from lead is difficult. When representing the families against their landlord, he brought in a toxicologist as an expert and had to not only quantify the extent of the damage the children suffered, but also prove what the long-term effect would be. In addition, there were the arguments to counter that the children’s impairment was caused by something other than lead.

Still, some former residents of West Calumet — including several children — are continuing their fight in the courts.

In Baker, et al. v. Atlantic, et al., 19-3159 and 19-3160, the families are claiming the former manufacturers at the site contaminated the environment then failed to warn residents. As a result, they say, they lived and played “on what is essentially a toxic waste dump with no knowledge of the dangers to which they were being continually exposed.”

Currently, the case is awaiting oral arguments at the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals. The defendants appealed after the Northern Indiana District Court granted the plaintiffs’ motion to remand the case to Lake Superior Court. Senior District Court Judge Joseph Van Bokkelen ruled the manufacturers were unable to show that their actions were performed under the color of federal office.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.