Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA home is an anchor.

Being able to return each day to the same address enables individuals and families to build stable lives and weather just about any storm that comes.

“Obviously employment is immensely important,” said Tom Crishon, legal director at Indiana Disability Rights, listing the elements people need for self-sufficiency. “Transportation is immensely important. Health is immensely important. But if you don’t have a roof over your head and a place where you can lay your head at the end of the day, all of that is adversely affected.”

Ten years ago, the Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana opened its doors in Indianapolis to help Hoosier tenants and homeowners keep their anchors. The small agency, which covers an area of 24 counties and 2.5 million people, educates, advocates and enforces the laws and regulations that prohibit housing discrimination.

Crishon has been on the FHCCI board of directors for eight years and is currently the president. The center’s primary focus, he said, is to educate everyone about fair housing laws and try to fix the systemic discrimination that harms not only specific households but the community as a whole.

“It’s imperative for people to understand the history of fair housing and the impact housing discrimination has had on people who experience it so hopefully we don’t replicate it,” Crishon said.

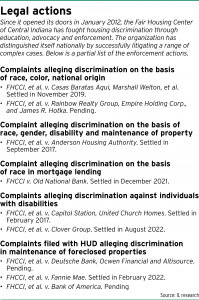

Nationally, the FHCCI has distinguished itself through the breadth and complexity of its legal work. The nonprofit does not have any attorneys on its staff of eight, but through the investigations and comprehensive research it does, the cases that emerge are well-prepared and ready for litigation by the time the attorneys are contacted.

Usually, FHCCI pursues an enforcement by filing either a complaint with the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development or a lawsuit in federal court. The center has taken action against appraisers, local housing authorities, banks, homeowners associations, apartments and landlords alleging discrimination on the basis of such things as sex, race, national origin, familial status and disability.

Many of the cases have ended with a settlement.

Many of the cases have ended with a settlement.

“The Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana is one of the most effective fair housing organizations in the country,” Sara Pratt, counsel at Relman Colfax in Washington, D.C, said. “They have been able to do effective investigation in multiple kinds of cases and do them very well indeed.”

Among the gains realized through FHCCI’s enforcement work is the financial impact. The total financial impact has reached $43.85 million, according to the center, which has been used to remedy victims and support community relief programs as well as to cover the costs for bringing the action and attorney fees.

‘It’s about you’

While discussing the work the center has undertaken in the past decade, Amy Nelson, FHCCI executive director, sat in the organization’s conference room and acknowledged the practical constraints of running a nonprofit. The agency has neither the resources nor the time to help every single person who calls or to address every instance of housing discrimination.

Who the FHCCI has not been able to help seemingly frustrates and saddens Nelson because she understands this kind of discrimination is personal.

“These cases are about the core of you, what makes you uniquely you and the emotional impact of that is far more devastating in many situations,” Nelson said, adding the pain cause by housing discrimination will be revisited every time the individual interacts with any housing provider. “It’s in the back of your mind, ‘Is this going to happen to me again?’ Once it happens once, it sticks with you because it’s about you. You are what caused this and it shouldn’t be like that.”

The FHCCI has a comprehensive approach to fair housing. It educates by offering trainings for professionals and information for consumers about the Fair Housing Act; it promotes fair housing through programs to help communities impacted by discrimination; and it works to convince elected officials to strengthen fair housing laws and policies.

In the area of enforcement, the organization has devoted some of its resources to address the deep-rooted discriminatory practices that can go unnoticed but still be very harmful.

An example of this systemic work is the center’s 2021 lawsuit against Evansville-based Old National Bank. Nelson said her team routinely analyzes the lending data of the banks serving central Indiana and noticed Old National was continually popping on the list of underperforming banks.

Within the Indianapolis-Carmel-Anderson Metropolitan Statistical Area, FHCCI found Old National was allegedly discriminating against Black residents who were seeking mortgages. From 2019 through 2020, the center claimed the bank made more than 2,250 mortgage loans, but only 37 were to Black borrowers.

The organization shared its findings with the financial institution and got assurances the bank was trying to improve. However, the practices continued, so the center filed a complaint in the Indiana Southern District Court in October 2021, alleging discrimination due to race in mortgage lending.

By December, Old National had agreed to a settlement that included originating at least $20 million in mortgages to majority-Black neighborhoods in Indianapolis and $1.1 million in loan subsidies.

Pratt, who was on FHCCI’s legal team for the Old National case, called the settlement “nationally significant.” She explained, “It included some provisions that were creative that will change things for the local community, that will invest money in the local community and help people who might not have had a chance to get homeownership or get ready for homeownership.”

Old National also championed the settlement.

“Our three-year partnership with the Fair Housing Center of Central Indiana is a natural extension of Old National’s long-standing commitment to provide resources and support to underserved communities in Indianapolis and throughout our footprint,” Kathy Schoettlin, Old National spokeswoman, said in an email. “We are grateful for the FHCCI’s partnership and proud of the services being provided to strengthen Marion County’s traditionally underserved communities, including down payment assistance and loan subsidy funds, new multi-family housing and homeownership and fair-lending education programs.”

Fostering change

Russell Cate, partner at RileyCate in Fishers, who was also on FHCCI’s legal team for the Old National litigation, said he was encouraged to start handling housing discrimination cases for the center by his colleague Matthew Keyes. Cate noted litigating under the Fair Housing Act requires a level of expertise because the federal law has nuances that can be missed by uneducated counsel.

He echoed other in crediting the success of the enforcement actions to FHCCI’s diligence.

The center, Cate said, first works to resolve the case by contacting the lenders or landlords directly. Yet, when litigation is necessary, the FHCCI does all the groundwork and number crunching to support the allegations. Such attention to the details not only helps the attorneys, he said, but also prevents further harm that could be caused by the creation of bad caselaw.

“If a case gets litigated and then appealed, you don’t want an appeal coming back because your case was weak to begin with, with an adverse appellate ruling that creates the precedent for fair housing law in the state of Indiana or nationally,” Cate said, noting the importance of devoting the time and effort to put together cases. “If you’re not filing and you’re not getting results like this, you’re not going to see a change.”

Looking ahead to the next 10 years, Nelson said he hopes the center will be able to expand its focus into other areas such real estate and insurance discrimination. The intent will remain to foster change by reducing discriminatory practices and, likely, litigation will be used as part of that work.

“Ever since the Fair Housing Act was passed in 1968,” Nelson said, “so much of the changes have happened through the courts.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.