Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowEven though he consistently uses the word “burdensome” to describe the consumer arbitration process, Teel Lidow believes the system provides a good way to resolve the kinds of small-value disputes that keep customers awake at night.

“There really never has been a good way to seek justice on a small scale … It’s been too inefficient,” he said. “The arbitration system is the first opportunity to build an efficient system where you could go after $100 disputes and get a fair outcome.”

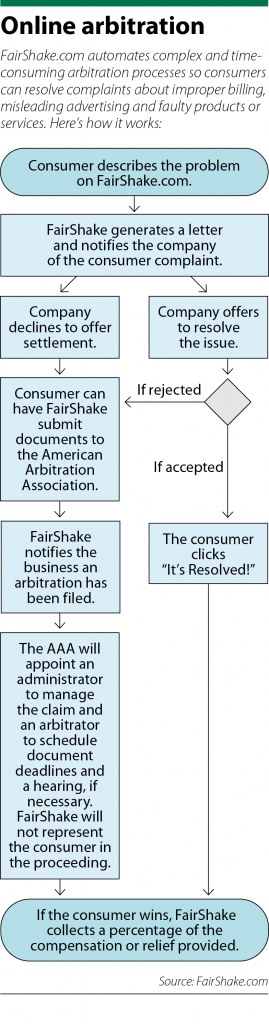

Lidow, an attorney and entrepreneur, has entered the consumer arbitration space as the CEO and founder of FairShake. This online service helps individuals navigate the arbitration process when they find a billing error or have a complaint about faulty products and services.

The website greets visitors with the assertion: “Big companies don’t play fair” and follows with the reassurance: “We’re on your side.” It includes an explanation of its services, recounts consumers’ success stories and starts the arbitration process after the wronged customer types in a brief description of the problem. Payment is collected at the end of the process if the consumer gets a refund or credit.

FairShake does not provide legal advice or legal representation.

Instead, Lidow explained, the company helps individuals navigate the arbitration process to try to recover what may be just a few hundred dollars. At a time when most Americans do not have the resources to cover a $400 emergency, according to the Federal Reserve, a small-value dispute can be critical to their financial wellbeing.

However, consumers are caught in a conundrum in that the dollar amount at stake is not large enough to justify hiring an attorney, he continued. Arbitration offers the mechanism to handle these kinds of disputes efficiently without necessarily needing to have a lawyer.

“I think it’s exciting and I think there’s a lot of opportunity in embracing this system and actually making it live up to that promise of being fair and efficient and accessible,” Lidow said.

Not everyone agrees.

Stephen Hayford is a professor of business law in the Indiana University Kelley School of Business and is an active labor, employment and commercial arbitrator. The arbitration process works best, he said, when the two parties involved are on equal footing, as when two businesses are in a dispute or when a labor union and company are trying to settle a workplace issue.

He traces the proliferation of arbitration, particularly in the consumer arena, to a series of decisions from the U.S. Supreme Court starting with Mitsubishi v. Soler Chrysler-Plymouth, 473 U.S. 614 (1985). The court turned the law of commercial arbitration “on its ear” by reinterpreting Section 1 of the Federal Arbitration Act of 1925 in a manner that Hayford believes is beyond what Congress intended.

The business professor concedes if the process is fair, simple and easy to access, arbitration could work for consumers, but he still harbors doubts.

“Do I think consumer arbitration can work? Yes,” Hayford said. “Is it easy to do? Probably not, because the big guy still has the upper hand.”

$300 million bill

As Hayford pointed out, consumers commonly have no choice about how they will solve any problems with companies. Whenever they open a bank account, get a credit card, or get a cell phone, they sign a contract that often requires them to arbitrate rather than litigate.

As Hayford pointed out, consumers commonly have no choice about how they will solve any problems with companies. Whenever they open a bank account, get a credit card, or get a cell phone, they sign a contract that often requires them to arbitrate rather than litigate.

Yet customers who feel they have been wronged rarely seek a remedy through arbitration. An analysis of data from the American Arbitration Association and JAMS found that despite the estimate of more than 80 million eligible claims from consumers and employees, only about 10,000 were resolved through arbitration.

Lidow attributes the low participation to consumers simply not being aware of arbitration. Those who do attempt to arbitrate encounter a system he said is too complex, full of administrative barriers and burdensome.

Consumers have to research to find and prepare the proper documents they need. They must do more research to find the company’s registered agent and then send papers through certified mail. After a certain period of time, the customers must find and prepare another set of documents and file those with the arbitrator who, again, they must search for.

“These things don’t necessarily require an attorney to help you, just filling in forms and sending them,” Lidow said. “But it’s enough of a hassle that it stops a lot of people just dead in their tracks.”

Often the arbitration agreements include a provision that bans consumers from bringing a class action lawsuit against the company. However, plaintiffs’ attorneys such as Travis Lenkner, managing partner at Keller Lenkner in Chicago, have countered this prohibition by filing thousands of arbitration claims on behalf of individuals when they suffer a common problem caused by the same business.

The firm is currently representing more than 5,000 drivers in a mass arbitration claim against DoorDash. In their claims filed with the American Arbitration Association, the drivers assert they were misclassified as independent contractors.

When DoorDash balked, the case moved to the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California, where Judge William Alsup granted the motion to compel arbitration in a February 2020 ruling. Michael Kun, an attorney with Epstein Becker Green estimated DoorDash could now be on the hook for more than $300 million in arbitrators’ fees alone.

“There’s definitely a place for arbitration and there’s a place for arbitration by a lot of people at the same time because that is the only way companies will be held accountable for certain types of conduct that otherwise would be addressed through class actions but can’t be,” Lenkner said.

Originally for lawyers

For individuals who are in a dispute with a company, Lenkner said those people would likely be on their own even if they were not required to arbitrate. The consumer who is not bound by an arbitration provision would likely have to litigate the dispute pro se in small claims court.

Echoing Lidow, Lenkner said the amounts of the individual claims are often too small to justify paying an attorney’s hourly rate. Also, most plaintiffs’ attorneys would not want to handle a single $500 dispute with the cable company on contingency because the return would not be worth their time.

His firm is able to offer its services and be confident of recouping its expenses later because of the volume of claims that come in a mass arbitration.

“We work on contingency basis, so a lot of the people we represent are lower-income folks who would not necessary be paying out of pocket for a lawyer for these kinds of claims,” Lenkner said.

Ironically, Lidow created an early version of FairShake to be a lead generator so attorneys could provide assistance to consumers with individual arbitration claims. The technology of process automation and document production removed the time-consuming busywork. Lawyers would be able to handle the disputes efficiently and potentially turn a profit.

Even so, attorneys were not interested in expanding their markets.

“I think everyone in this system could probably benefit from being fully represented by an attorney,” Lidow said, “… but what we found, there’s just really no appetite out there on the attorney part to provide this service.”

FairShake likely will have no shortage of people needing help.

The 2020 National Customer Rage Study has charted a steady increase in consumer frustration since the first such report was conducted for the White House in 1976. A full 66%, or two-thirds of American households, experienced a product or service problem within the past 12 months, up from 56% in 2017.

Also, the study reported that consumers made an average of 2.9 contacts with the company to try to resolve the most serious problem. This is a decrease from the average 4.1 contacts made in 2017.

Lidow is not surprised that consumers are walking away.

With the “millions of consumer transactions a year,” he said, errors are bound to occur. But when a company does not respond to a complaint, the customer may not know what to do. FairShake begins “turning the crank” by starting the arbitration process and getting the company’s attention.

Lidow sees his business as lifting some of the burden from consumers.

“We need some more efficient ways to help these folks because it’s just a huge and underexamined area of the access to justice gap,” he said.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.