Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowWith Indiana already incorporating two components from the Uniform Bar Examination into its own attorney admittance test, a study commission formed to review and recommend changes to state’s bar exam is advocating Indiana pick up the remaining component and transition completely to the UBE. But three commission members cautioned against the move, saying the state would be relinquishing control of its own test.

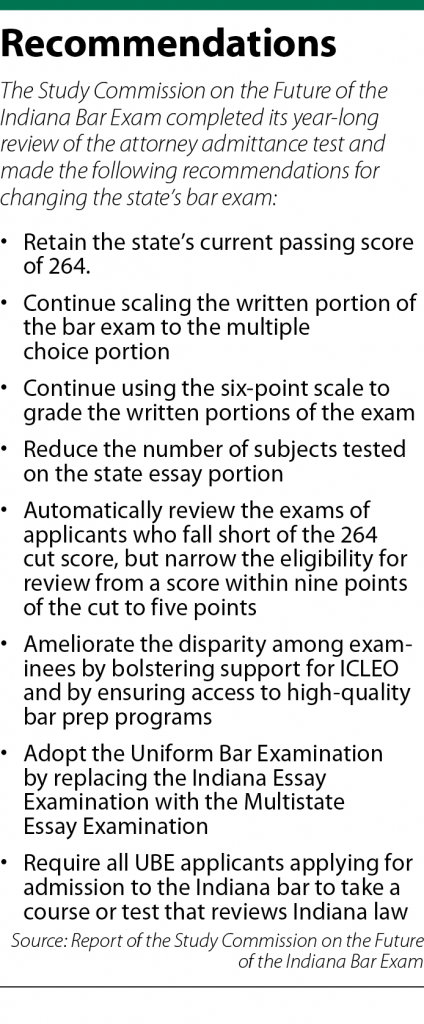

The Study Commission on the Future of the Indiana Bar Exam concluded its 11-month evaluation and submitted its final report to the Indiana Supreme Court on Dec. 15. Appointed by the Supreme Court, the commission was charged with evaluating the Hoosier bar exam and recommending potential changes.

Predominately, the group found that applicants to the Indiana bar face a “cognitive overload,” because the 18 distinct subjects they have to study outpace the 12 topics tested in UBE jurisdictions. As a consequence, Indiana examinees are at a disadvantage, consistently scoring below the national average on the multiple choice portion of the exam and struggling to pass the bar overall.

The majority of the commission advocated for joining 36 other jurisdictions and adopting the UBE as a way to reverse the declining passage rate. However, as an alternative if the national bar exam is not implemented, the commission suggested the number of subjects covered on the Indiana essay exam be reduced from the current 11 topics.

The majority of the commission advocated for joining 36 other jurisdictions and adopting the UBE as a way to reverse the declining passage rate. However, as an alternative if the national bar exam is not implemented, the commission suggested the number of subjects covered on the Indiana essay exam be reduced from the current 11 topics.

Retired Indiana Chief Justice Randall Shepard, chair of the commission, noted revising the bar exam would not be unprecedented. Indiana first implemented the bar exam in 1931, then made some significant alterations in 2001 when it moved away from the all-essay format. Changes made in the past helped ensure that only those lawyers who met a minimum level of competency were licensed to practice in the state.

The commission has concluded the Indiana Bar Exam now needs to evolve again. “That’s our position,” Shepard said. “It would be better for the profession and the public. It’s not a moment for standing still.”

Shepard and Indiana Court of Appeals Chief Judge Nancy Vaidik, the commission vice chair, met with the Indiana justices to discuss the report, according to the Indiana Supreme Court. Chief Justice Loretta Rush and the associate justices thanked the commission leaders for their dedication to providing the thorough analysis.

The Supreme Court said it is considering the next steps and, as part of that process, will seek public comment on the report’s findings.

Viewpoint: Shepard, Vaidik say it is time to reform the Indiana Bar Exam.

Indiana focus

Shepard and Vaidik characterized the adoption of the UBE as making a “modest” change.

In its current format, they explained, the Indiana Bar Exam already uses two components of the UBE: the Multistate Bar Exam, which is the multiple choice section, and the Multistate Performance Test, the section that asks examinees to write a letter or brief applying the law to a hypothetical fact scenario. Transitioning to the UBE would only require Indiana to swap its own essay section for the Multistate Essay Examination.

“I would put it more at the tweaking stage,” Vaidik said of the recommended change. “Now 70% of the bar exam is already the Uniform Bar Exam, so what we’re really talking about is the last 30%.”

Even so, three members of the commission viewed the adoption of the UBE as troublesome and wrote a separate letter outlining their concerns. Barnes & Thornburg partner John Maley, one of the dissenters, co-led a review of the Indiana Bar Exam by the Indianapolis Bar Association, which issued its findings in 2017. At that time, the task force concluded the UBE presented too many drawbacks for Indiana to adopt but said further study of the national test was warranted.

Maley maintains the UBE is still not right for the Hoosier state. He said Indiana has recorded a “significant decline” in bar passage rates since the MBE and MPT were adopted in 2001. In addition, moving to the UBE would force the Indiana Board of Law Examiners to distribute the grades for the written portions of the test across a six-point scale “rather than seeking to identify minimal competence on each question.”

The dissenters also worried the UBE would decrease the attention given to Indiana law. However, Shepard saw little reason for concern since, he said, Indiana, like many other states, has been amending its statutes to overlap with, for instance, the Uniform Commercial Code. As a result, the differences in the laws between the states have been diminishing.

Still, Maley sees a need for the bar exam to continue to focus on state law. “There are certainly areas of Indiana law, such as the Uniform Commercial Code, in which Indiana has only minor variations,” he said. “However, many core areas of Indiana law confronted regularly by the bench and bar are unique in Indiana.”

Fairness benefit

Shepard and Vaidik said the overriding benefit of the UBE is the test’s fairness and reliability. Legal professionals along with psychometricians and other experts craft, review and pretest the questions before they become part of the graded exam. This is done to remove any built-in bias and to make sure the questions do measure minimal competency.

Moreover, Shepard and Vaidik said, the examiners in Indiana would continue to grade the MPT and MEE sections. But they would receive special training to maintain the consistency in the grading.

As for the nuances of Indiana law, the commission is recommending UBE applicants be required to complete a day-long seminar, test or combination of the two that would focus on statutes specific to the state.

Maley said he is apprehensive that while such a program would be very important, the audience would not be as attentive or as invested as the current applicants are in the bar preparation courses. Conversely, Bradley Skolnik, executive director of the Indiana Office of Admissions & Continuing Education, sees an advantage to the special seminar.

“I think the state component proposed by the commission can be an even more effective way of imparting the unique characteristics of Indiana law than merely testing on the broad 11 topics we test on now,” Skolnik said. “(The instructors) will be able to focus like a laser on the areas where Indiana has some unique characteristics and potential traps for the unwary.”

Disparity gap

Included in the commission’s report is a call to ameliorate the disparity in the passage rate among particular groups of examinees. Shepard described the recommendation as a reminder for “ongoing vigilance.”

The commission found that lower test scores are more likely linked to socioeconomic factors. Bar applicants who have to work while studying for the exam and are not able to take time off during the week or two prior to the test will, on the whole, have a harder time passing. Still, the report noted immediate steps can be taken address the disparity, such as enhancing the Indiana Conference for Legal Education Opportunity (ICLEO) program and providing more access to bar preparation courses.

Shepard said even though the bar exam cannot fix the societal issues that hinder passage, there should be an effort to make sure the low pass rate is not a product of the test itself. To that end, the commission asked the Marion County Bar Association to research if other UBE states had tracked the passing rates by ethnicity and race of the examinees to determine if the test harbored any biases against minorities.

Julian Harrell, president of the Marion County Bar Association, said while the anecdotes are well-known about the disproportionate impact of bar exams in general, the empirical evidence is scant. Few states are measuring the outcomes of different groups, the association learned.

Before Indiana rushes to collect such data, Harrell warned that asking questions about race and ethnicity would be controversial. His concern is that the information could be subsequently misused to discriminate against minority examinees. He advised that any gathering of such information be done with great sensitivity and that the resulting data be treated with the same level of privacy as personal medical records.

Yet Harrell does believe the discussion about the disparity is worth continuing.

“I think the commission should be commended for at least caring enough to ask the question” about disparity on the bar exam pass rates, Harrell said. “It shows some level of concern and connection to the scope of people taking the bar.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.