Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe former Purdue University undergraduate called it a “Kafkaesque process.”

Only identified as John Doe, the one-time Boilermaker was accused and ultimately found responsible by the university for sexually assaulting his former girlfriend. He has continually denied the allegations, but after an investigatory procedure that he claims violated his due process rights and discriminated against him because he is male, he was suspended from the university for one year, starting in June 2016, and had to involuntarily resign from the Navy ROTC.

Doe then turned to the federal courts for relief. After the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of Indiana dismissed his complaint, he pressed forward. Last month, the 7th Circuit Court of Appeals heard oral arguments in John Doe v. Purdue University, et al., 2:17-cv-33.

This was the first time the 7th Circuit had heard a case filed against a university by a former student who was accused and found through the school’s investigatory process to have sexually harassed or assaulted another student. However, the number of these kinds of lawsuits is rising nationwide, and the Chicago circuit court has two similar cases on its docket, both of which are suits filed against schools in Illinois.

Brooklyn College history professor KC Johnson has become a critic of how colleges and universities are handling allegations of sexual misconduct. In general, Johnson said, schools have established procedures that incorporate no meaningful investigation and do not provide any way for the accused to defend themselves.

As evidence, he pointed to the increase in lawsuits. According to his records, an average of one lawsuit has been filed every week in federal court by an accused student for the last 2½ years. Most of the lawsuits end in settlements because, he said, universities do not want to go through the discovery process and a trial.

“I think the purpose of a university is to pursue the truth,” Johnson said. “In this system, pursuing the truth or finding out what happened is not the number one priority.”

Jennifer Drobac, an Indiana University Robert H. McKinney School of Law professor, maintains false accusations are very rare. She believes the rise in complaints reflects the growing awareness of sexual violence. Society is just now realizing the “breadth and depth” of the problem, she said.

A member of the IU faculty since 2001, Drobac served on the university-wide committee that formulated new procedures after the Obama administration put out new guidelines for handling sexual misconduct on college campuses. The goal, Drobac said, was more than just complying with the new standards, but to make sure every IU campus was safe for all students. The committee members all wanted a fair procedure for investigating sexual harassment and assault complaints, as well as one that was transparent and protected the privacy of all the parties involved.

“I think there’s still work to be done,” Drobac said. “It’s very hard for large universities to ignore the consideration of liability. I would much prefer this to be about truth and justice and equal opportunity and education, but we have to be realistic that liability matters.”

Doe claimed the process that found him responsible did not have a hearing of any kind. There was no cross-examination, no sworn testimony. He was not allowed to see the investigators’ report and was not allowed to provide evidence that supported his side of the story. Rather, he asserted, “there was no presumption of innocence but rather a presumption that the accusing female’s story was true.”

Johnson noted the most unusual aspect of the Purdue case was that the accuser did not appear before the university’s three-member advisory panel. Rather, the accuser submitted a statement that had actually been written by the school’s Title IX coordinator and director of the Center for Advocacy, Response and Education.

Johnson is sympathetic to victims and said he understands developing a process to examine these complaints is difficult. Still, he said, as the lawsuits indicate, the result has been an “unbelievably unfair process for the accused.”

‘Dear Colleague’

The rise is these cases is linked to the 2011 “Dear Colleague letter” issued by the U.S. Department of Education under the Obama administration. Although it was described as providing only guidance for how institutions of higher education should handle sexual harassment and sexual violence on their campuses under Title IX, colleges and universities have said the Education Department’s Office for Civil Rights set and enforced standards inconsistent with caselaw.

OCR’s investigations would span several years, starting with the issue highlighted by the complaint but then expanding into a comprehensive look at the school’s entire Title IX program. It was not a transparent process, and often the schools had to sign off on the resolutions without seeing the agreement. Schools that did not comply risked losing all federal funding, including Pell grants and research grants.

“In its review of colleges’ compliance with Title IX, OCR’s investigation often had a punitive impact that was not measured to the complaints or to the supporting colleges as they attempted to fairly address a very serious and complex issue,” said Dana Scaduto, a former board chair of the National Association of College and University Attorneys and a graduate of IU McKinney.

The Dear Colleague letter was a response to the common belief that colleges and universities were not dealing with sexual assault complaints properly. They were not perceived as being aggressive enough in their responses to assault victims and survivors.

Virtually every college and university overhauled its procedures, which Scaduto said was a positive step in ensuring more sensitivity in this complex issue. However, she continued, the challenge remained to create a process that maintained the schools’ obligations of responding to the needs of the accuser and being fair to both the accuser and to the accused as allegations are reviewed and resolved.

Carly Mee, interim executive director SurvJustice, a national nonprofit that advocates on behalf of survivors of sexual violence, disputes the argument that the Dear Colleague letter caused colleges and universities to change their policies. Rather, Mee said the letter ended some confusion by making clear what the schools were required to do when they received a complaint of sexual misconduct from a student.

The result, Mee said, has been that survivors are receiving better support. They can come forward with their allegations and be protected from a hostile environment, she said.

‘Ultimate scarlet letter’

‘Ultimate scarlet letter’

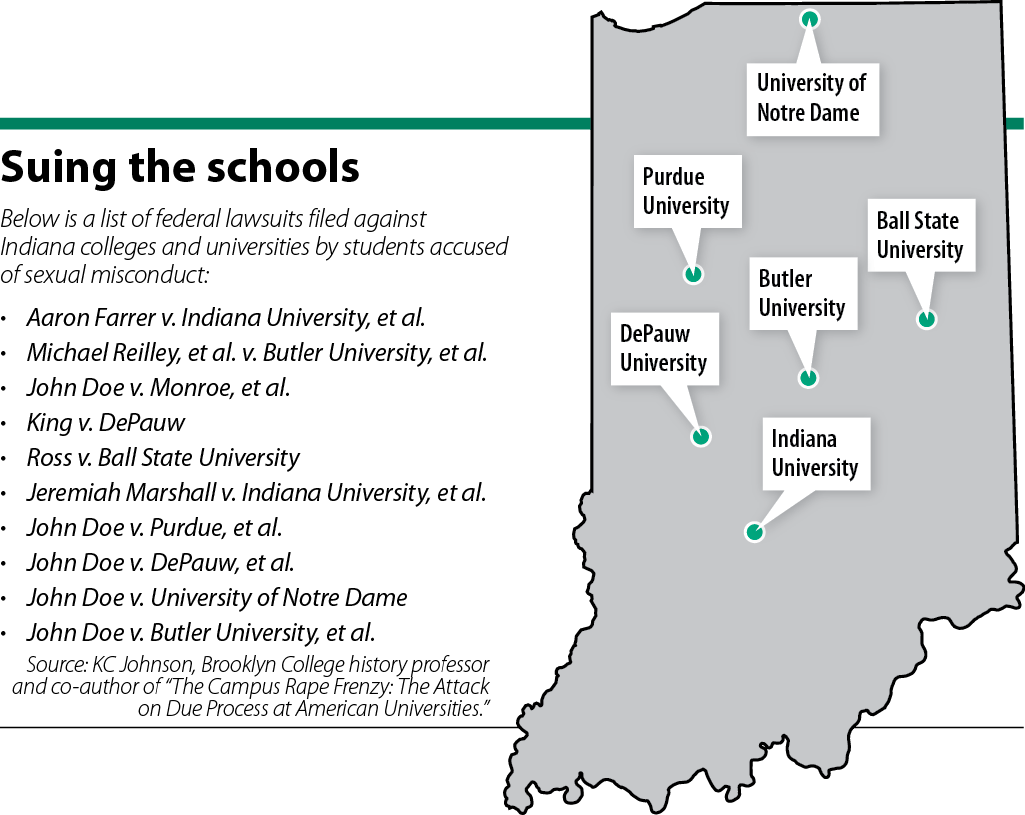

At present, 10 federal lawsuits have been filed by the accused against six Indiana colleges and universities, according to Johnson’s research. Plaintiffs make a variety of claims, including that the allegations are false, investigatory processes were biased against males and the accused never had the opportunity to present their stories.

One accused filed a complaint even after the university cleared him of the allegations. In Michael Reilley, et al. v. Butler University, et al., 1:17-cv-04540, the school’s Equity Grievance Panel unanimously ruled the accused was not responsible and the evidence indicated consent had been given.

Yet, during the investigation, the university put a hold on his records and did not release his transcripts in time for him to transfer to Indiana University. Reilley was forced to enroll in a small Illinois college for a semester, but none of the credits he earned counted when he finally entered IU.

Attorney Eric Rosenberg of Rosenberg & Ball Co., LPA, in Granville, Ohio, described being accused and found responsible for sexual misconduct as the “ultimate scarlet letter.”

Since representing the accused son of a friend about seven years ago, Rosenberg estimates these kinds of cases comprise 95 percent of his practice. He has filed more than 20 lawsuits across the U.S. on behalf of the falsely accused and has provided counsel to upward of 100 students in the university process.

The discipline actions that result from these proceedings follow the accused, Rosenberg said. They will struggle to get into another school and establish their careers. One client of his was rejected by five different law schools because of the allegations, he said, and two others committed suicide.

“This is forever life-altering,” Rosenberg said.

Coming changes draw controversy

Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos is poised to release new regulations regarding campus sexual assault and harassment that are expected to reverse some of the Dear Colleague guidance. Overall, the new standards are expected to give colleges and universities more flexibility in how they handle these kinds of allegations from students.

Victims and victim-advocacy groups have criticized the reversal. The outcry is being sparked by the expectation that the new regulations will provide protections for the accused, prohibit complainants from remaining anonymous and require the accusers to be available for cross-examination.

Also, victim advocates are pushing back against the presumed change to the standard of evidence. The Dear Colleague letter advised colleges and universities to use the lower standard of preponderance of the evidence, while under the new regulations, the expectation is that the schools will move to the higher standard of clear and convincing evidence.

“The rollback is a problem,” Drobac said. “Women are getting the message that if they do come forward, it will be a very difficult, retraumatizing process, and they’re very likely not going to be able to prove their case.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.