Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA group of incarcerated women at the Indiana Women’s Prison in Indianapolis has researched and gathered information on the origins of the facility formerly known as the Indiana Reformatory Institute for Women and Girls.

That research will soon become public via a book set to release this month.

The book, “Who Would Believe a Prisoner? Indiana Women’s Carceral Institutions, 1848-1920,” scheduled for release to the public on April 25, was made possible by the Indiana Women’s Prison History Project, which in 2016 won the Indiana Historical Society’s Indiana History Outstanding Project award.

The book has been a long time coming — the scholars began their work a decade ago and had to navigate their research through what is and is not allowed in prison, and through pages and pages of printed documents.

“It really shows what incarcerated people are capable of intellectually, and that often gets overlooked, perhaps especially incarcerated women, but incarcerated people in general,” Elizabeth Nelson, a faculty member in the history, medical humanities and health studies departments at IUPUI and co-editor on the book, said.

History of abuse

The book project came about through Kelsey Kauffman, who was formerly the director of educational programming at the Indiana Women’s Prison. Kauffman designed a course that explored some of the original documents from the founding of the facility.

While the evidence of abuse and corruption uncovered through that research wasn’t necessarily surprising, one thing was: evidence of medical experimentation being performed on incarcerated women by Theophilus Parvin, the prison doctor from 1873-1883.

For Nelson, the most interesting find was information about the historical intersection of incarceration and medicine.

“I was perhaps most interested in and most excited by some of the aspects of the research that were really tying the history of the carceral state, the history of prisons, to the history of medicine — seeing the medical experimentation but also the uses of incarceration for eugenic purposes that was going on in Indiana very early on in the history of eugenics,” she said.

The prison itself was founded to protect female inmates from abuse at the hands of their male counterparts. But allegations of abuse continued, despite the sex-based separation.

The title of the book, for example, comes from the story of Eva Green, a prisoner who was sexually assaulted by a steward in the prison’s hospital. When she took the matter to court, the prison warden served as the lawyer for the steward and told the judge to not trust the woman. The steward then walked free.

Attorney Margaret Christensen, whose practice partially focuses on legal ethics, said wardens have the responsibility to do their jobs, but it can get tricky.

“The warden is in charge of an institution that has been kind of in charge of a prisoner herself, and so there’s probably an argument there that you need to be impartial in administering the prison,” Christensen said.

Patrick Olmstead, another attorney focusing on legal ethics, noted prisoners have the ability to write to judges directly if they need protection.

But, Olmstead added, “It’s a really tough situation. The tough part is the judge gets flooded with pro se letters.”

Allegations of abuse in prisons continue today, including in Indiana.

A recent example comes from Clark County, where former jail officer David Lowe is facing felony charges of escape and official misconduct, as well as a misdemeanor charge of trafficking with an inmate. Lowe is accused of selling two male inmates access keys to the interior of the Clark County jail in exchange for $1,000, allegedly giving the men access to multiple female pods.

The October 2021 incident has been dubbed a “night of terror” for the female inmates, who claim they were “raped assaulted, harassed, threatened and intimidated” for “several hours.”

Then-sheriff Jamey Noel strongly denied the allegations of abuse against the female inmates, going so far as to create a website dedicated to debunking the allegations. Noel is no longer sheriff, as he was term-limited at the end of 2022, according to WDRB.

A federal case related to the abuse allegations is ongoing in the Indiana Southern District Court via Coomer, et al. v. Noel, et al., 4:22-cv-79.

Lowe is scheduled for a jury trial on Sept. 5 in the case of State of Indiana v. David Jason Lowe, 10C01-2110-F5-000262.

Incarceration in Indiana

The release of “Who Would Believe a Prisoner?” coincides with the release of new data showing a rise in female incarceration across the nation.

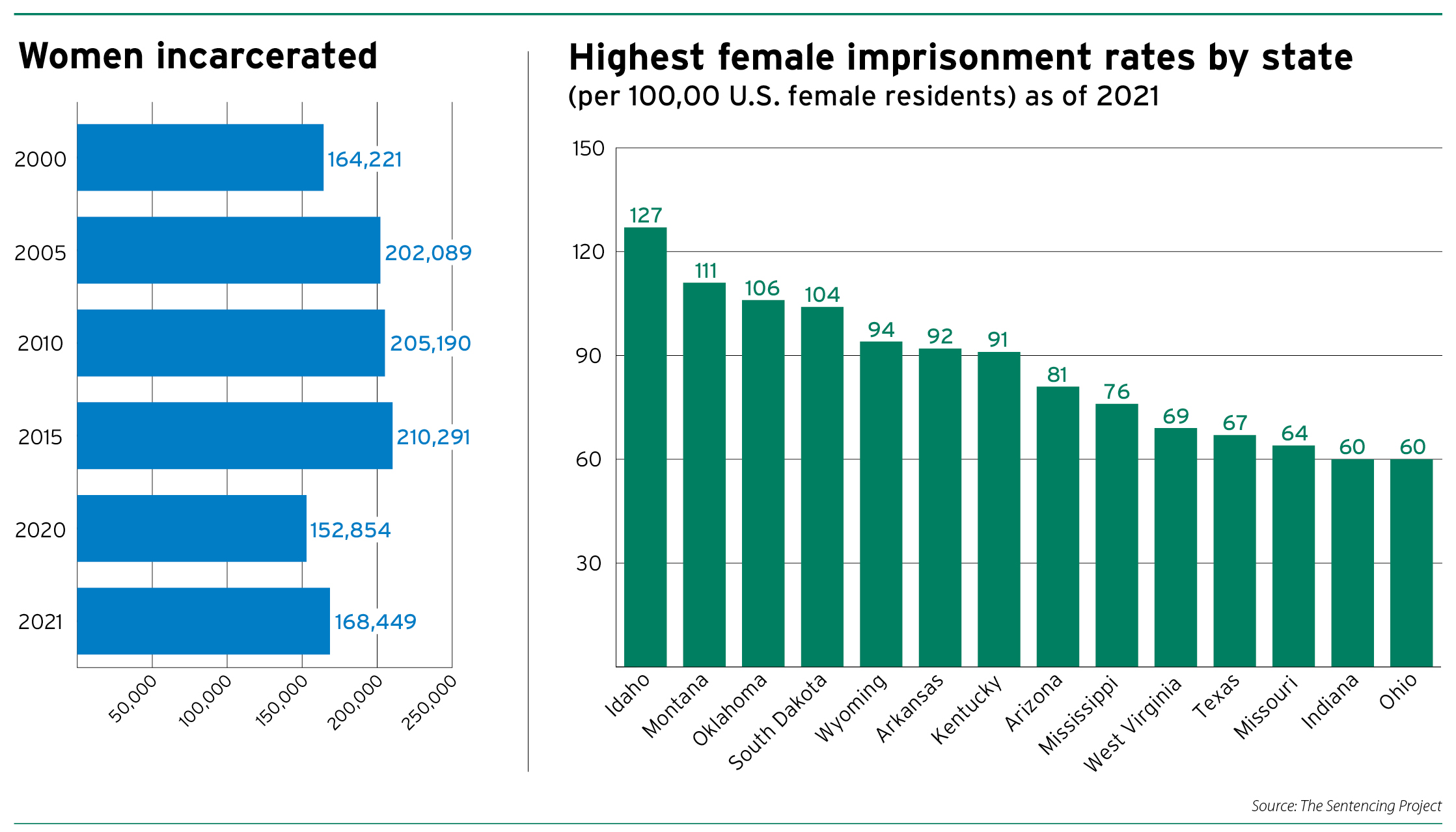

While there have been modest changes in the number of women incarcerated in recent years, including a notable dip in 2020, compared to 40 years ago, the increase is stark.

In 1980, 26,326 women were incarcerated in a federal or state prison or a jail. By 2021, that number was 168,449 — a 539% increase, according to data from The Sentencing Project.

In 1980, 26,326 women were incarcerated in a federal or state prison or a jail. By 2021, that number was 168,449 — a 539% increase, according to data from The Sentencing Project.

The highest number reported by The Sentencing Project was 210,291 in 2015 — a 698% increase from 1980.

Among all 50 states, Indiana ranks 13th in terms of women’s incarceration, with 60 female inmates per 100,000 U.S. female residents, as of 2021. The Hoosier State’s female incarceration rate is tied with Ohio’s.

“We can look at sentencing policies, so that plays a big role in the number of women that we have seen enter the criminal justice system,” Kristen Budd said, research analyst at The Sentencing Project, said.

Aside from the number of women incarcerated, The Sentencing Project’s report also showed that 711,125 women were on probation and 96,386 were on parole in 2021, for a total of 975,960 women under the supervision of the criminal justice system nationwide — greater than the population of the city of Indianapolis.

The report also noted that 58% of women incarcerated in state prisons have a child under 18.

“It definitely has huge, huge ramifications on children who are now attempting to cope with having their mother who was incarcerated,” Budd said. “We also see in the research that that can create huge instability for those children. We have a lot of individuals who are in jail or prison who do have children and that’s something we do need to address, especially with reunification when we have individuals coming out.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.