Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowThe way the federal court system addresses sexual harassment complaints should be clearer and fairer moving forward now that the federal judiciary has made clarifying amendments to its workplace conduct rules.

The changes come several months after a public hearing was held on proposed amendments to the Rules for Judicial Conduct and Disability, Code of Conduct for U.S. Judges and the Code of Conduct for Judicial Employees.

Those amendments were offered in response to a list of recommendations released by the Federal Judiciary Workplace Conduct Working Group in June 2018, which discovered inappropriate conduct in the federal judiciary was “not pervasive” but also “not limited to a few isolated instances.”

Formed at the request of United States Chief Justice John G. Roberts, the working group noted the federal judiciary was ultimately not immune to the issue of sexual harassment. Thus, Roberts called for the evaluation of the federal judiciary’s standards of conduct and procedures for investigating and correcting unwanted sexual advances.

Formed at the request of United States Chief Justice John G. Roberts, the working group noted the federal judiciary was ultimately not immune to the issue of sexual harassment. Thus, Roberts called for the evaluation of the federal judiciary’s standards of conduct and procedures for investigating and correcting unwanted sexual advances.

All of this came after 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals Judge Alex Kozinski abruptly retired from his position after accusations from more than a dozen women accusing him of sexual misconduct. That incident sparked the federal judiciary’s holistic response to address workplace harassment by amending its conduct rules accordingly, said Judge Sarah Evans Barker of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Indiana.

Barker serves as a member of the Judicial Conduct and Disability Committee, one of two groups that met jointly to hear testimony on the proposed amendments before their enforcement in March. Southern District Judge Tanya Walton Pratt serves on the Code of Conduct Committee, which heard testimony alongside the JC&D Committee.

After a year of study and consideration, the judiciary’s national policymaking body approved the proposed package of workplace conduct reforms last month. Barker says the amended rules better spell out the expectations and requirements for how judicial employees should behave.

“There were generalized standards that you weren’t supposed to treat people inappropriately or in a demeaning way, but we didn’t lay out exactly what that means as we have now,” Barker said. “The judiciary as a whole recognized that we need to be more specific about this; more intentional and thorough.”

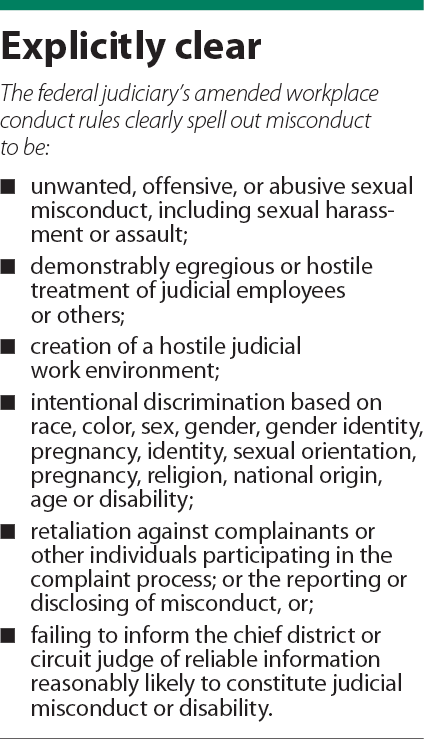

What the federal judiciary says was formerly implicit concerning conduct expectations is now explicitly clear under the amended rules. Misconduct includes “unwanted, offensive, or abusive sexual misconduct” as well as “sexual harassment or assault.”

Duty to disclose

Changes to the codes and rules also clarify the duty of judges and judiciary employees to disclose and report misconduct if they are privy to such information, and that confidentiality obligations should never be an obstacle to reporting misconduct or disability.

That was a real issue that judicial employees seemed to face when confronting workplace harassment, according to Indiana University Maurer School of Law professor Charles Geyh.

“There were women subjected to harassment who went to other judges for guidance who said, ‘Confidentiality rules don’t let us talk about this.’ The new rules make it clear that confidentiality restrictions don’t protect information about judicial misconduct,” he said.

For those caught in the middle of misconduct, Geyh said the fear of retaliation might prevent individuals from raising the issue in a formal complaint. That hesitation might stem from fear of jeopardizing future careers or uneasiness about going above a judge’s head in order to report misconduct.

The rules note that complaints regarding such misconduct may be dismissed in whole or in part if found to not threaten to be prejudicial to the partiality and effectiveness of the judiciary. But if the complaint is more innocuous, Barker said, levels of redress are still available to handle the issue informally.

A fruit of that response, she said, is the Office of Judicial Integrity, created for employees to receive advice and guidance regarding workplace conduct issues, as well as report harassment.

Laying a framework

Geyh, who testified in favor of the proposed rule changes last fall, said they seem to stay the course with what was initially suggested. He said he is pleased with the implemented reforms and noted that the federal judiciary appears to be taking a meaningful approach to more seriously address misconduct and harassment claims going forward.

“It will go one of two ways: this is just window dressing and the judiciary will return to a quiet, confidential process that doesn’t air its dirty laundry … but I don’t think that will happen,” Geyh said. “I think the sentiments this judiciary realized is that this is a legitimate problem. This system is not shot through with sexual harassment, but there is enough that they need to act.”

Indiana University McKinney School of Law professor Jennifer Drobac agreed, stating that the amended rules have an increased level of flexibility and a good, basic structure for the federal judiciary to proceed.

“There seems to be a sincere effort to move forward and advance equality and give equal opportunity for everyone,” Drobac said. “I think these rules are an effort to set an example that people should take the issue seriously. And apparently some judges need that message.”

However, Drobac noted that while she applauds the federal judiciary for taking steps to address harassment, she is disappointed that the rules do not apply to members of the U.S. Supreme Court.

“We have two U.S. justices who have been accused of sexual harassment or sexual assault,” Drobac said. “I would like the Supreme Court to be held to the same rules that their brothers and sisters have.”

Back home, Barker said she hasn’t seen the issue of sexual harassment as a prevalent problem within the Southern District court. But she knows the issue exists nationally and is gaining momentum as a result of the #MeToo movement.

“Everybody’s consciousness has been raised,” she said. As a result, she noted steps are being taken across the country to address the issue — starting in her Indianapolis chambers.

Employees within the U.S. District Court, Bankruptcy Court, and Probation Office for the Southern District of Indiana are currently receiving harassment prevention training, according to Southern District Clerk Laura Briggs. The training was developed subsequent to and reflective of the federal judiciary working group’s report.

Barker noted that not every judicial employee is guilty of harassment, but because the issue surfaces with enough regularity, the judicial branch has made it a point to acknowledge that such behavior is not tolerated.

“And it won’t be tolerated,” she said. “Even by a judge who has life tenure.”•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.