Subscriber Benefit

As a subscriber you can listen to articles at work, in the car, or while you work out. Subscribe NowA concussion lawsuit filed against the NCAA presented an issue of first impression and prompted the Indiana Supreme Court to develop a framework for trial courts to use when deciding discovery disputes involving executives or high-ranking officials in an organization.

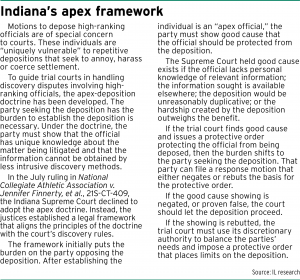

Some federal and state courts have relied on the so-called apex-deposition doctrine to determine when an individual at the “apex” of a company or nonprofit could be required to sit for a deposition. However, in July, the Indiana Supreme Court rejected the doctrine and created a framework that aligns with the court’s trial rules.

That framework was announced in National Collegiate Athletic Association v. Jennifer Finnerty, et al., 21S-CT-409.

Brian Paul, partner at Faegre Drinker Biddle & Reath, is a member of the legal team representing the NCAA in the litigation. He said the Supreme Court’s opinion alerts trial courts not to reflexively rubber-stamp motions to depose witnesses who occupy a leadership position

“There is a lot of what I would call open space, but not because of any defect in the opinion,” Paul said. “It’s simply because the court recognized that whether a showing of good cause has been made is ultimately a discretionary determination that depends on all of the fact and circumstances.”

Attorneys Robert Dassow, Nicholas Deets and Tyler Zipes of Hovde Dassow + Deets are representing the families who brought the lawsuit. They did not respond to a message seeking comment.

The case is continuing in Marion Superior Court.

Annoy, harass, coerce

The case that went before the Supreme Court was a consolidation of three lawsuits brought on behalf of former college football players who alleged they sustained several concussions during their playing years.

Cullen Finnerty played at the University of Toledo and Grand Valley State University between 2001 and 2006; Andrew Solonoski Jr. was on the team at North Carolina State University between 1966 and 1970; and Neal Anderson played at the University of Illinois between 1960 and 1964.

Following college, the lawsuits state the three athletes suffered from a range of physical and mental conditions. Ultimately all three were diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, which has been linked to repetitive brain trauma, and died.

Following college, the lawsuits state the three athletes suffered from a range of physical and mental conditions. Ultimately all three were diagnosed with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE, which has been linked to repetitive brain trauma, and died.

The plaintiffs asserted the NCAA was aware of the dangers of concussions but failed to establish concussion-management protocols to protect the athletes. Consequently, the plaintiffs dispatched deposition notices to the NCAA for Mark Emmert, president, Donald Remy, chief legal officer and chief operating officer, and Dr. Brian Hainline, chief medical officer.

In its ruling, the Supreme Court recognized that high-ranking officials can be “uniquely vulnerable” to repetitive depositions. Parties might use depositions for “non-truth-seeking purposes, such as to annoy, harass, or coerce a settlement.”

Paul reiterated the Supreme Court’s opinion is a reminder for trial courts to be mindful of people in leadership positions.

He noted the Indiana framework is contrary to the apex doctrine, where the party seeking the deposition must show why the executive should be deposed. Under the new Hoosier method, the party opposing the deposition must show good cause for protecting the high-ranking official.

“The (Supreme Court) also said, ‘You trial courts have to take into account the circumstances that are sort of unique to apex officials,’” Paul said. “In other words, ‘You can’t necessarily treat them like every other witness because they’re … in a unique position that makes them particularly vulnerable to numerous repetitive and potentially harassing depositions.’”

Jon Noyes, an attorney at Wilson Kehoe Willingham, explained that getting the view of the executive is often necessary. Leaders are the brains, the hearts and the hands of their organizations, he said, and deposing them can provide a behind-the-scenes look at whatever issue is being litigated.

“They’re involved in a lot of these very high-level or even specific corporate policies that we often use to prove our case to show that a policy wasn’t followed or it wasn’t implemented correctly,” Noyes said. “A lot of times these executives have insight into these policies because they’re the ones that have either been behind making them, they may have information on their purpose and they may have information on their implementation.”

Noyes was not a party to the concussion lawsuit and talked in general terms about deposing high-ranking officials. He did not comment on the specifics of this case.

No bald assertions

While recognizing the vulnerabilities of executives, the Supreme Court emphasized they needed to have good reasons with factual support as to why they could not be deposed. They cannot just assert they are ignorant of the issue and be excused.

The Indiana framework provides four elements that would establish good cause: the executive lacking personal knowledge of the relevant information in quality to that available elsewhere; the information sought being available through a less burdensome method; the deposition being unreasonably cumulative or duplicative; and the hardship accompanying the deposition outweighing its likely benefit.

If the trial court finds the executives make their good cause showing, the plaintiffs can file a motion that either negates or rebuts the order. That requires the trial court to review the grounds for good cause and then deny the defense’s request to protect the executive from the deposition or place limits on the deposition.

Noyes said he sees the Supreme Court as being careful and not allowing an apex determination to be made solely on the defendant’s say-so.

“The (defense) must show that there is good cause to protect this apex person from the deposition,” he said. “And in order to do that, they need very specific factual support. The court was very careful to say that, ‘You can’t just rely on bald or conclusory assertions. You need to really do your due diligence and really prove that there is good cause.’’’

On remand, the Marion Superior Court applied the framework.

Emmert and Hainline were ordered to sit for depositions, but the court found Remy, who is no longer an employee of the NCAA, was not properly served to have his deposition as an individual nonparty witness.•

Please enable JavaScript to view this content.